NYC's Housing Supply Crisis is Two Separate Problems

Supply for the vast majority of New Yorkers, and supply for the very poorest // These problems must be disambiguated // Supply for the vast majority is the key to addressing both supply problems

New York City’s housing supply crisis is often mistaken for one problem. In reality, it’s two distinct problems stacked in a trench coat: (1) a general supply shortage that affects most New Yorkers, and (2) a chronic supply/affordability crisis for the very poorest that is exacerbated by the first problem.

Problem One: an overall supply shortage that drives up prices for most New Yorkers, well over 50% of the income distribution. This is heavily contingent on policy, and is temporary in “normal” market conditions.

Problem Two: a chronic affordability crisis for the very poorest that is sharply exacerbated by the first problem. NYC has always struggled to address this problem, even as it has repeatedly solved the overall supply crisis with supply bursts in the past.

Here are my contentions about these two supply problems:

Past New Yorkers bisected housing shortages this way.

Problem one must be solved as an urgent emergency1, because problem two is likely unsolvable in New York’s political economy until problem one is solved. You can work on both at the same time, and their solutions can overlap in policy, but problem one must absolutely be solved with policy ruthlessness. Not only because it affects far more people, but because it is the gateway to solving the problem for those concerned with problem two.

Problem one is addressed through radically increasing the production of market-rate housing of all kinds (and the government has a role to play here).

Problem two is addressed through a mix of social housing policies, like vouchers, public housing, and rent adjustments that don’t ruin building finances. But problem two likely can’t be solved without problem one being solved—for example, how can you disperse vouchers for housing units that don’t exist?

Current elected politicians still prioritize solving problem two at the direct expense of problem one, which means they will solve neither one nor two. They misunderstand the nature of the supply crisis (that it is generally two separate problems), and so they botch the policy response.

Let’s look at each contention with more detail.

#1) Past New Yorkers understood their “housing shortage” as two separate shortages

New York’s post-WWI housing shortage was just as devastating as the modern one, if not worse.2 And it was largely solved via state policy by unleashing a torrent of market-rate housing to correct the balance of supply and demand. New Yorkers who stayed in the city during covid, which was a demand shock, will recognize what increasing supply relative to demand can achieve in the following testimony delivered to New York State’s Stein Commission3 in 1925 (emphasis added):

The spokesmen for the landlords told a very different story. Questioned by A. C. McNulty, counsel to the Real Estate Board, and Harold M. Phillips, counsel to the Greater New York Taxpayers Association, they testified that as a result of the recent surge of residential construction, the housing shortage was over. Indeed, said Ernest Tutito, a Brooklyn real estate man, it had ended at least nine months earlier. Plenty of vacant apartments were available in New York, some for six to seven dollars a room, said John H. Hallock, and others for as little as three to five dollars a room, added Isidor Berger. To keep old tenants, many landlords were reducing the rent. And to attract new tenants, others were offering concessions of as much as two months’ free rent…The crux of the problem, Stanley M. Isaacs said, was that at no time in the history of New York City, especially not since the passage of the Tenement House Act of 1901, had apartment houses been built for “the very poor.” This was a chronic problem, not an emergency. (The Great Rent Wars, p.392)

This testimony does two big things:

Recognizes that increasing supply can end a supply-driven housing crisis, bring down rents, and increase tenant power relative to landlord power, and

Divides the “housing supply” problem in two, and carves out housing for “the very poor” as a separate problem that has been chronic throughout New York’s history, and is sometimes coincident with a larger supply crunch for the general population.

You will find this same supply crisis bisection in a 1960 overview of the post-WWI housing supply crisis:

There was, in 1920, a desperate need for housing of all kinds, and tax exemption provided housing in great quantities. Supply and demand appeared to have reached a near-normal ratio by 1925, largely as a result of tax exemption. However, the increased supply did not include adequate provision for low-income tenants. As this became more obvious, attempts to link tax exemption with some kind of control became more persistent. The crisis had been averted by the exemption, but the more permanent problem — the inability of private initiative to provide accommodations for those with low incomes — remained unsolved. (How Tax Exemption Broke the Housing Deadlock in New York City, 1-11)

Indeed, this is how I, and many others, bisect the current supply crisis. It is one large supply crisis that affects most New Yorkers, and is solvable with much higher provision of market-rate housing, just like the post-WWI shortage. It is also a coincident, chronic problem of supplying housing to the poorest New Yorkers, that is made much worse by the overall supply crunch. You can solve the problem for most people via massive supply alone.

For reference, here is the 1920s housing supply boom that the two excerpts above reference:

#2) Each of the two shortages requires different policy tools that sometimes overlap, and the overall shortage must be solved in order to also solve the shortage for the poorest

Solving the housing shortage for the vast majority of New Yorkers is straightforward, but not easy

The larger shortage, the one that affects the vast majority of New Yorkers, can be solved by unlocking vast amounts of market-rate supply; I argue that case here, and our rent regulation laws state it outright. We have overwhelming evidence of this, but the two largest pieces are probably:

We have repeatedly seen what happens when supply outstrips demand, in obvious fashion; the 1903-1916 and 1920s booms, with vacancy rates in the 5-8% range and a renter’s market that dwarfed covid prices, are undeniable proof. No major structural constraints have changed such that we should expect a different outcome today.

The covid demand shock was a live experiment that shows what happens when demand goes down relative to supply, and everyone saw it. Rents fell precipitously, landlords offered free months of rent, and all this happened with a vacancy rate of just 4.54%,4 compared to our current rate between 1-2%.

Clearly increasing supply relative to demand works, and it works on a broad basis for most New Yorkers. Covid did this in the suboptimal way—crashing demand and driving people from the city. We can do this in a healthy, positive-sum way by increasing supply that has many other positive effects, like increased political power and nicer apartments.

But this does not seem to as directly alleviate the housing problems that the poorest New Yorkers face, past or present.5 If you are making very little or no money, the market—especially in an expensive place to build like New York—will struggle to give you many options (although it will still give you some options if it’s allowed to, and it does even now when it’s generally not).

NYC’s programs to help low- and middle-income people

New York City and State have plenty of programs to assist those who struggle with rent to this degree. For example:

NYCHA (New York City Housing Authority) public housing, which houses about 500,000 New Yorkers in ~178,000 units.

Our city voucher program, where individuals are given vouchers that function as cash to pay rent.

Rent freezes tied to property tax offsets to keep buildings financially stable: SCRIE (Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption) and DRIE (Disability Rent Increase Exemption). These are pronounced “scree” and “dree,” and both rhyme with “eel.”

There are even programs that try to help people get on the property ladder, and/or are aimed at more middle-income people:

Past example: the limited-profit developments of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, completed in 1924 pursuant to Chapter 658 of the Laws of 1922.6

The Mitchell-Lama program was signed into law in 1955, and provides rental and ownership opportunities for moderate- and middle-income New Yorkers. It was recently made more famous by Timothée Chalamet.

New rent-regulated apartments tied to income, available via lottery.

The problems NYC has serving low- and middle-income people

However: it is important to note that these solutions often don’t work, or don’t work that well, if you have not solved problem one, the city’s overall supply crunch. For example:

Lower housing supply hurts renters of all income brackets, and this includes people who are searching for housing with vouchers. Sure, you can give someone a voucher; but is there an easily findable place for them to use it?7

Many higher-income people, themselves facing staggering rental costs, will compete for lower cost apartments; they will do this in ways that are legal and illegal, and in ways that are legal but don’t comport with a law’s spirit. They will compete with lower income renters, and outcompete them. Or, many lower-income people might wind up outcompeting a moderately wealthy family. Severe supply shortages wreak havoc on the intended outcomes of government programs.

Further: these programs operating successfully are contingent upon a government that is agile and works sufficiently well. In the modern era, we (1) have not solved the overall supply problem (largely thanks to bad laws and legislators who don’t fully understand the supply problem, see the next part of this essay), and (2) don’t have a government that is agile enough to implement these programs well, although a new generation is working to right the ship.

NYCHA is the “city’s worst landlord.” It is also the largest, by far. It looks like good private partnerships can help fix this.

Most people have not heard of the financially sustainable versions of a rent freeze, SCRIE and DRIE. Elected officials often instead push blanket rent freezes with no financial offset that are currently pushing vast amounts of our rent regulated stock into physical and financial ruin.

The city’s housing voucher system is still largely dysfunctional. The city didn’t even give landlords the option of accepting electronic payments until less than a year ago (as opposed to paper checks), and the general administration of the program is running behind basic modern efficiency practices.8

The housing lottery is overwhelmed with applications (certainly driven in part by the general supply crunch), and cannot cope. The city announced reforms to fix the problem in 2020…that did not work. They are making a another attempt in 2025. As with the NYCHA reforms, these city changes draw on the private sector.

Mitchell-Lama developments are facing increasing problems, often directly tied to supervising government agencies. See this 2024 report from the State Comptroller which provides a sober, concerning look at the problem. These are not new problems in many ways, but they are deteriorating and must be addressed.

#3) Current elected politicians still prioritize solving problem two (and other problems) at the direct expense of problem one—and so don’t solve either

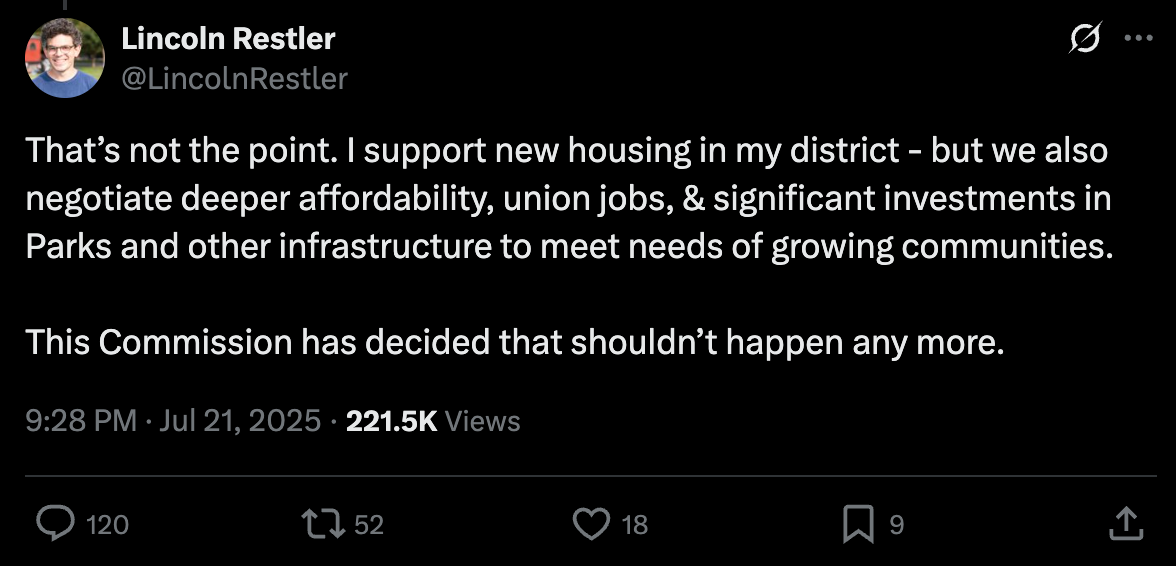

Many New York City politicians do not yet embrace the policies that would actually solve our housing supply crisis, which they have re-certified for decades. The X post above from NYC Council Member Lincoln Restler outlines the relatable, but ultimately mistaken, thinking behind many of their housing policy decisions. In my words:

We cannot allow developers to build housing that requires council discretionary review without them paying for a variety of other public and private goods, and without cross-subsidizing below-market rents somehow.

This thinking emerged as the post-WWI supply crisis abated, when there was more breathing room to address problem two (housing for the poorest):

As the tendency, from 1925 onward, was to replace emergency legislation with legislation of a more permanent kind, the most effective of the emergency laws were to be considered seriously as a possible part of the plan to solve the permanent housing problem. Tax exemption was to become a part of the permanent housing policy, but it was to be granted only after the profit motive in building had been eliminated, or minimized through the application of the limited-dividend principle. (How Tax Exemption Broke the Housing Deadlock in New York City, 1-11)

While I think there is plenty of room for policy interventions like Mitchell-Lama and other programs I mentioned above, it is self-defeating to extend the thinking as far as CM Restler has done in practice. He is unfortunately joined by a majority of the city council in this mode of thinking.

In the first place, housing developers are already providing a good that the city needs—housing, and housing that complies with current/proposed zoning and construction codes. They have done their part. Forcing them to negotiate with the council on so many other things, or even facing the prospect of such a negotiation, wildly depresses housing production, and advantages only the largest developers who can afford the lawyers and planners to conduct such negotiations (and sustain years of operation without actually having rent revenue come in the whole time). This makes the end-result housing more expensive, and produces less housing overall.9 This has been the status quo for decades.

Further: most of the housing that New Yorkers of all income levels live in—the bulk of which was produced in market-rate building booms earlier in the twentieth century—was not subject to this kind of negotiation. It would likely not exist if it had been! The weight of evidence across the decades and last century shows that the only way to alleviate the general supply crisis—and resulting affordability crisis—is to similarly unleash housing production in the modern context.

CM Restler’s position is that the vast bulk of this needed market-rate housing (which currently lies behind discretionary up-zonings and other policy changes) should be allowed only insofar as it meets a long list of other demands negotiated with the City Council.

My summary response to CM Restler’s position:

The intentions are good.

The path to Hell is paved with good intentions.

Evidence does not support this approach, if your goal is sufficient housing production to end our supply crisis.

An honest contemplation of the historical record repeatedly shows how increased supply, with a vacancy rate beyond 5%, is fantastic for renters. We got a brief taste of it through covid’s demand crash. It could be so much better, and sustained, with supply. I strongly disagree with any policymaker who is not sprinting to replicate those circumstances, which means solving “problem 1.”

Restler’s approach not only throttles our ability to solve the overall supply crisis for most New Yorkers, but also prevents us from addressing it well for the poorest New Yorkers.

This is Blue Tape. This is everything bagelism. It simply does not work. Turn on the housing production firehose and let it flow (which, in a city as non-built-up as NYC, doesn’t require dramatic changes)10, and focus your policymaking on responding to the housing as we watch it grow. Do not focus your policymaking on whether to allow housing, which the city council as an institution is still disinclined to do, certainly to the levels required to exit our supply crisis. We have better models of legislative involvement, and better models of legislators willing to meet the moment.

Conclusions

It is vital to recognize that New York City’s housing supply crisis is two separate supply crises: supply for the vast majority of New Yorkers, and supply for the very poorest. These have different solutions, and solving the problem for the poorest requires solving the problem for most people. And solving the problem for most people should be the high priority for a democratic government by default.

Elected officials who prioritize policies that throttle market-rate production insure that we cannot effectively solve the housing supply crisis for both most people and the poorest people. They are the equivalent of a doctor who will only allow cancer treatment insofar as it helps a patient’s chronic, unrelated anemia. For heaven’s sake, treat the cancer aggressively! It will make treating the anemia more tractable!

History’s lessons are unambiguous on this front, but bringing them into full view requires a bisected view of the supply issue NYC faces. Critically, modern legislators need to avoid the well-intentioned, but self-defeating, temptation to heavily condition new housing supply.

They are supporting a legal regime that might work out in some individual cases, but generally comes with the opportunity cost of solving the housing supply crisis for both most people and the very poorest.

Bibliography

Fogelson, Robert M., The Great Rent Wars: New York, 1917-1929. United States: Yale University Press, 2013.

How Tax Exemption Broke the Housing Deadlock in New York City: A Report of a Study of the Post World War I Housing Shortage and the Various Efforts to Overcome It. Special Committee on Tax Policies Organized by Citizens' Housing and Planning Council of New York, Inc., 1960.

Title page summary: “A report of a study of the post World War I housing shortage and the various efforts to overcome it, with particular emphasis on the four-year period of 1921- 1924, during which limited exemption was granted from local taxation for all new buildings intended exclusively for dwelling purposes.”

An Introduction to the New York City Rent Guidelines Board and the Rent Stabilization System. Staff of the Rent Guidelines Board, 2020.

2021 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey Selected Initial Findings, “The Rental Inventory and Vacancies The 2021: Net Rental Vacancy Rate,” NYC Department of Housing Preservation & Development, May 16, 2022.

Some books that lay out policy interventions to create low- and middle-income housing, which I did not pull into this piece in the interest of brevity, but will use in upcoming posts:

Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies That Transformed a City. Edited by Nicholas Dagen Bloom and Matthew Gordon Lasner. United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Bloom, Nicholas Dagen. Public Housing That Worked: New York in the Twentieth Century. United States: University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated, 2008.

Fogelson, Robert M.. Working-Class Utopias: A History of Cooperative Housing in New York City. United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 2022.

Garodnick, Daniel R.. Saving Stuyvesant Town: How One Community Defeated the Worst Real Estate Deal in History. United Kingdom: Cornell University Press, 2021.

Relevant Maximum New York posts:

A Renter's Market, If You Can Keep It: How NYC's Past Housing Booms Unlocked Tenant Power, Unit Quality, and Choice (July 2025).

The Original Subways Were Approved By NYC's Legislature in One Week (May 2025)—a faster model of legislative approval.

Call It Blue Tape (March 2025).

The Role of Market-Rate Rental Housing in New York City (January 2025).

New York's Rent Regulation Laws Say Housing Supply Is the Answer (January 2025).

Brief Historical Thoughts on Empowering People to Build in NYC (January 2025).

2025: New York City's Electoral College Election (January 2025).

While many housing supply advocates use the word “emergency” and “crisis,” I’m looking for a different phrase. This “emergency” is more than a half-century old. So while it is an “emergency” in the sense that it makes the whole economy and political economy more brittle and susceptible to upset, it clearly does not demand a response. People and the government often even demand policies that will make it worse.

A numeric accounting of the post-WWI housing supply crunch in NYC:

As expected, residential construction picked up after the war. But the revival soon sputtered and then died out. Americans were perplexed. “It is but natural that lack of building during the war should have resulted in a scarcity of housing,” wrote one observer in March 1919. “What now mystifies people, however, is that building does not go forward with a rush.” By spring residential construction was back in the doldrums, where it stayed for the rest of the year. During 1919, a year in which the city’s population rose by almost 115,000, New York’s builders erected only 95 apartment houses, with just over 1,600 units, even fewer than in 1918 and fewer by far than in any year since the turn of the century. Things were bad in Brooklyn, where 62 apartment houses (with only 600 units) went up, and even worse in the other boroughs. In the Bronx, builders erected only 24 apartment houses (with just over 800 units). In Queens—which, said a Jamaica real estate man two weeks after the Armistice, was “on the even of the biggest building boom in its history”—they built only six apartment houses (with fewer than 70 units). And in Manhattan, which had more people than any American city except Chicago, they constructed only three apartment houses (with fewer than 140 units). For every apartment house put up in New York in 1919, two were knocked down. The city’s builders erected more than 6,600 one-family homes and more than 2,300 two-family houses in 1919, the great majority of them in Brooklyn, Queens, and Richmond [Staten Island]. But this did little to offset the slowdown in apartment house construction.

—The Great Rent Wars, “The Postwar Housing Shortage,” pp.26–27

Background on the Stein Commission:

Under the circumstances Governor Smith did in April 1923 what most other governors would have done: he asked the legislature to set up a new state agency [the Commission of Housing and Regional Planning]…As Smith saw it, the commission would serve two purposes. If it found that the [housing] emergency still existed and the legislature voted to extend the emergency rent laws, he could not be blamed if the laws were held unconstitutional. And if the commission reported that the emergency was over and the legislature decided to let the emergency rent laws expire, he would be insulated to some extent from the political fallout. In mid-August [1923] the governor’s office announced that Clarence S. Stein, the former secretary of the Reconstruction Commission’s Housing Committee, would chair the Commission of Housing and Regional Planning, which would henceforth be known as the Stein Commission.

—The Great Rent Wars, “The Extension of Rent Control,” p.365

For the contemporary covid-era vacancy rate, see:

2021 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey Selected Initial Findings, “The Rental Inventory and Vacancies The 2021: Net Rental Vacancy Rate,” NYC Department of Housing Preservation & Development, May 16, 2022, p.25.

“The net rental vacancy rate in 2021 for all housing accommodations in New York City was 4.54 percent.”

It does help them in the medium and long-term though, because abundant supply pushes down the bottom end of market prices more broadly, making it easier for poorer New Yorkers to access them. It also prevents wealthier New Yorkers from competing for housing with the poorest.

See here for a broad discussion of life insurance company housing broadly, and page 7 specifically for a table that includes the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company 1924 development.

See the discussion on housing supply and vouchers more broadly in this Furman Center report, with specific reference to footnote 47.

Every time someone reads about this law they think “Wait, the city wouldn’t send electronic payments to landlords until now?” Correct. Although if you read the transcript of the hearing (pp.59-64) where this law was discussed, it doesn’t seem close to being fully rolled out, even after this law.

From “Findings”: “The length and complexity of the review process increases development costs: a two-year-long discretionary approval process can increase development costs by 11 percent to 16 percent, depending on a project’s size and financing, assuming no other changes in a project’s scope.” The discretionary approval process is the one CM Restler wants to maintain, although it is uncharitable to say he wants to maintain it because of these cost increases. But I do think his cost-benefit analysis is wrong.

“A look at the buildings reveals a shocking fact: Outside of Manhattan, 63% of all properties within one kilometer (1KM) of a subway have two stories or less, while 92% are three stories or less.”

From “Left Hand Meet the Right Hand: New York’s Failure to Implement Transit-Oriented Development” by Jason Barr (January 2023).

Agree that that increasing the production and thus the supply of market rate housing units (for sale or rent) is a key to solving the affordability problem. But isn’t part of the problem a change how residential units and land zoned to allow their production are being consumed? When units purchased or rented as pied-a-tierre they are not available to individuals or families shopping for a full-time residence. https://rpa.org/news/lab/nyc-hits-new-pied-tierre-peak-amidst-housing-crisis

Nor are units lost to consolidation, perhaps to accommodate a family comfortably, but also to recreate gilded age size mansions. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/19/nyregion/nyc-apartments-housing-crisis.html

And some of the largest new luxury towers fill massive interior space with very large units (thus relatively few), many of them uses as pied-a-terre. https://www.6sqft.com/infographic-how-nycs-supertalls-compare-in-height-and-girth-to-international-towers/