A Renter's Market, If You Can Keep It: How NYC's Past Housing Booms Unlocked Tenant Power, Unit Quality, and Choice

The historical record is clear: high vacancy rates (5–8%) are great for renters, and more supply can get us there. NYC has solved housing supply crises before.

City legislators need to hear the stories of the historical record. The past has the most effective advocacy we can offer, but it can’t come testify. Email these stories to your CM (kindly); I’d love to hear when you have. Unless they hear these stories, I don't think they’ll really believe what's possible in their bones—humans need stories! They, and most people, imagine the status quo but a little better. But the reality would be transformative.

New York City has experienced the following phenomenon many times in its history:

We have a housing supply shortage and a low vacancy rate, resulting in terribly high prices for everyone, and a lack of good rental options.

The city builds a ton of market-rate housing, the vacancy rate climbs, and tenants get lower prices, lots of bargaining power, and higher quality housing.

This post is a collection of long excerpts that depict this phenomenon happening.

The post-consolidation building boom of 1903–1916

Please read pages 17–20 of Robert Fogelson’s The Great Rent Wars: New York, 1917–1929 (2013).

You can read the PDF of scanned pages here.

Now some highlights from those pages, all bolded emphasis added. The circumstances you read about here occurred with a vacancy rate between 5–8% (currently we sit between 1–2%).

Supply far outstrips demand, solves housing problems

Starting in 1903, a building boom got under way the likes of which New Yorkers had never seen. With labor plentiful, building materials relatively inexpensive, and, most important of all, capital readily available, builders erected everything from posh high-rise apartment houses on Manhattan's East and West sides to modest five- and six-story walk-ups in Brooklyn and the Bronx. As one observer wrote in the middle of the boom, “It is doubtful if New York City, or indeed any other city of the world, ever before witnessed the expenditure of so many millions of dollars in the construction of tenement houses during a similar period.”

By the time the boom came to an end in late 1916, the builders had transformed much of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. In less than a decade and a half they had erected nearly 27,000 apartment houses with close to 400,000 units. To put it another way, more than 40 percent of all the apartments in New York in 1916 had been built since 1903. The new construction was enough to house the population of every American city except Chicago. Even more noteworthy, it was enough to offset the steady growth of New York, whose population rose by well over a million in the decade before the United States entered World War I. It was also much more than enough to offset the loss of about six thousand old-law tenements, with roughly forty thousand apartments, which were demolished to make way for parks, schools, roads, and commercial buildings, chief among them the new Pennsylvania Railroad Station. With supply running well ahead of demand, the number of vacant apartments soared, reaching more than 67,000 in 1909, or enough to house the population of Washington, D.C. So did the vacancy rate, which was compiled by the city's Tenement House Department. By early 1909 it had reached 8.1 percent, which was unheard of in New York. And in early 1916, by which time the boom was winding down, it still stood at 5.6 percent, which was nearly twice as high as normal, according to Tenement House Commissioner Frank Mann. (18)

Tenant bargaining power went through the roof

For the many New Yorkers who had long been hard-pressed to find a decent apartment at a reasonable rent, the soaring vacancy rate provided a golden opportunity. And they seized it, noted Abram I. Elkus, a close ally of Governor Alfred E. Smith. Thousands of families moved out of old-law tenements on the Lower East Side and into new-law tenements in Brooklyn and the Bronx, where they found “much better apartments,” with plenty of light and air and even hot water, toilets, and bathtubs. Often they moved not once but many times. They “moved from one apartment to another upon the slightest inducement,” said one real estate man. They moved so often, remarked another, that New Yorkers maintained their reputation as "the most restless population in the world.” Knowing they had “the upper hand,” as one real estate man put it, prospective tenants drove a hard bargain. Said another, they “could pick, choose, demand and dictate to the limit and no man could say them nay. This condition existed for ten long, weary years.” Current tenants drove a hard bargain too. As Jacob Leitner, a Manhattan landlord, later recalled, tenants would come to him and say, “Mr. Leitner, if you don't give us a month's free rent in July we are going to store our furniture [and move] to the country for July and August. You give us that month's retn [sic] free, we agree to stay. [Otherwise we] won[']t sign any lease.” (19–20)

Landlords desperately competed to woo tenants. Do not be so quick to denounce the economic role of “speculators”!

Desperate to fill their apartments, New York's landlords went to great lengths to get tenants and hold them. They not only made repairs, but also painted and otherwise “decorated” the apartments—often, lamented one real estate man, “according to the whim and caprice of the tenants.” Some even attempted to attract new tenants by offering to pay their moving expenses and to give them a ton of coal. Perhaps the most striking sign of the landlords’ desperation was their willingness to grant “concessions,” free rent for a month or two—and occasionally even longer. Although some real estate men deplored this practice, many landlords found the logic of concessions irresistible. Most tenements, perhaps as many as 90 percent, were erected not by long-term investors, but by speculative builders, who were anxious to sell the buildings as soon as they were finished, pay off the first and maybe second and third mortgages, and then begin work on another building. Their problem was that the value of the property depended above all on its rent roll-not its rental income. (20)

The 1903–1916 boom ends when supply catches up to demand in 1917, and stays stuck due to the economic constraints of WWI

Fed up with years of what the head of a major real estate firm called “abnormally low” rents, some landlords gave up and watched as banks and other mortgagees foreclosed on their properties. In the hope that conditions would improve, others held on, doing what they could to stay a step ahead of their creditors, sometimes even digging into savings to pay interest, taxes, and other charges. Starting in early 1917, however, there were signs that things might be looking up. At long last, demand was catching up with supply. “Practically every desirable building is booked to its capacity,” the Times wrote in January. Even new apartment houses still under construction were half rented. By April one real estate man predicted that unless the price of building materials declined, which was highly unlikely, “there is going to be a scarcity of apartments.” Before long, landlords stopped offering concessions and for the first time in years began raising rents. (20)

The 1920s building boom

The next two excerpts are from Robert Fogelson’s The Great Rent Wars: New York, 1917–1929 (2013).

The severe supply crisis that had to be solved prior to the 1920s

As expected, residential construction picked up after [World War I]. But the revival soon sputtered and then died out. Americans were perplexed. “It is but natural that lack of building during the war should have resulted in a scarcity of housing,” wrote one observer in March 1919. “What now mystifies people, however, is that building does not go forward with a rush.” By spring residential construction was back in the doldrums, where it stayed for the rest of the year. During 1919, a year in which the city’s population rose by almost 115,000, New York’s builders erected only 95 apartment houses, with just over 1,600 units, even fewer than in 1918 and fewer by far than in any year since the turn of the century. Things were bad in Brooklyn, where 62 apartment houses (with only 600 units) went up, and even worse in the other boroughs. In the Bronx, builders erected only 24 apartment houses (with just over 800 units). In Queens—which, said a Jamaica real estate man two weeks after the Armistice, was “on the even of the biggest building boom in its history”—they built only six apartment houses (with fewer than 70 units). And in Manhattan, which had more people than any American city except Chicago, they constructed only three apartment houses (with fewer than 140 units). For every apartment house put up in New York in 1919, two were knocked down. The city’s builders erected more than 6,600 one-family homes and more than 2,300 two-family houses in 1919, the great majority of them in Brooklyn, Queens, and Richmond [Staten Island]. But this did little to offset the slowdown in apartment house construction. (26–27)

By the mid-1920s, rapidly increased housing supply created a landlord-tenant relationship similar to the 1903–1916 building boom

The spokesmen for the landlords told a very different story. Questioned by A. C. McNulty, counsel to the Real Estate Board, and Harold M. Phillips, counsel to the Greater New York Taxpayers Association, they testified that as a result of the recent surge of residential construction, the housing shortage was over. Indeed, said Ernest Tutito, a Brooklyn real estate man, it had ended at least nine months earlier. Plenty of vacant apartments were available in New York, some for six to seven dollars a room, said John H. Hallock, and others for as little as three to five dollars a room, added Isidor Berger. To keep old tenants, many landlords were reducing the rent. And to attract new tenants, others were offering concessions of as much as two months’ free rent… (392)

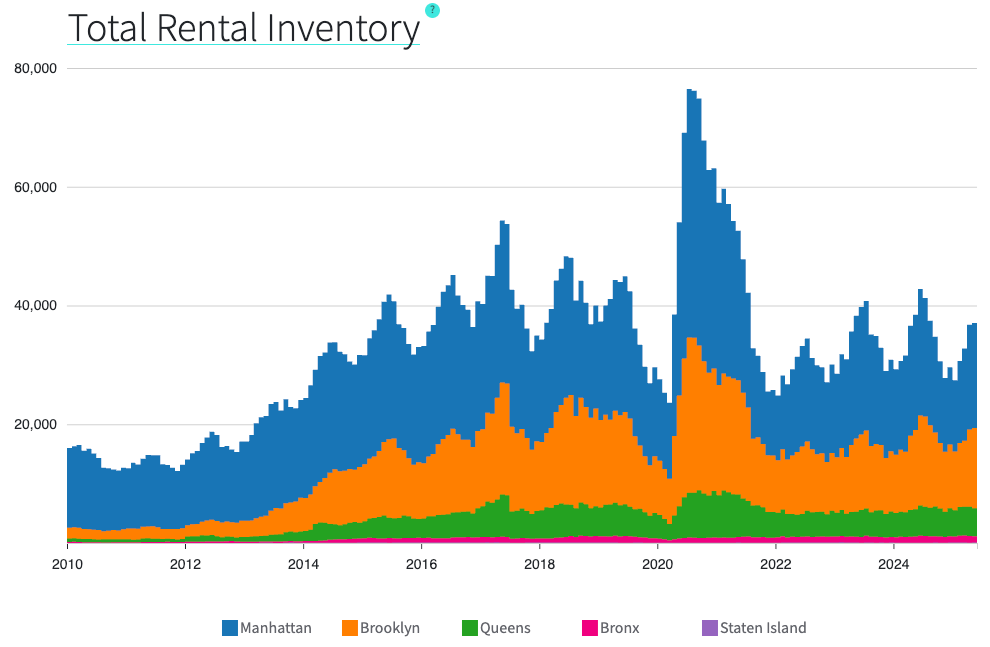

Here is what the 1920s boom looked like, with a vacancy rate topping out above 8%, just like the 1903–1916 boom:

And here is the narrative description of this boom from An Introduction to the New York City Rent Guidelines Board and the Rent Stabilization System (pp.19–20, emphasis added):

The Emergency Rent Laws of 1920 were adopted in the wake of dramatic increases in dispossess proceedings and a collapse in new construction caused by a diversion of resources to the [first world war] effort…

The housing shortage of the early 1920’s was severe. Vacancy rates fell below 1% from 1920 through 1924. To induce new construction, the City exempted all properties built between 1920 to 1926 from property taxation until 1932. In addition, all units constructed after September 27, 1920 were exempt from the rent laws. Notwithstanding the presence of relatively strict rent protections for existing units, new construction proceeded at a record pace, with hundreds of thousands of new apartments being added to the stock before the decade ended. By 1928 the City’s vacancy rate was approaching 8% and rent regulations were no longer needed. A phase out began in 1926 in the form of luxury decontrol – exempting units renting for more than $20 per room per month. After 1928 apartments renting for $10 or more, per room, per month were excluded. The Rent Laws of 1920 expired completely in June 1929, although limited protections against unjust evictions were continued.

The gruesome honorable mention: the 2020–2021 covid demand shock

The two supply booms detailed above share a few characteristics:

They saw vacancy rates hover between 5–8%.

They created newer apartments that tenants had broad-based power to chase at lower prices.

They show that improvements to apartment safety and quality can coincide with more affordability, if supply and improved methods are allowed.

They still significantly mark our overall built environment, since we have built so relatively little since they occurred.

They occurred when New York City had more “green field” development potential relative to today. But NYC is still wildly under-built, and most New Yorkers’ intuitions (natives and otherwise) are completely miscalibrated on this front. “A look at the buildings reveals a shocking fact: Outside of Manhattan, 63% of all properties within one kilometer (1KM) of a subway have two stories or less, while 92% are three stories or less.”1

One major difference: the 1903–1916 boom occurred “naturally,” and the 1920s boom had to be jump-started by state tax exemption policy. But both were heavily facilitated by the subway, which was still expanding rapidly during these times (although people were always trying to kill it).

Unfortunately, we haven’t seen a comparable housing boom since the 1920s.2

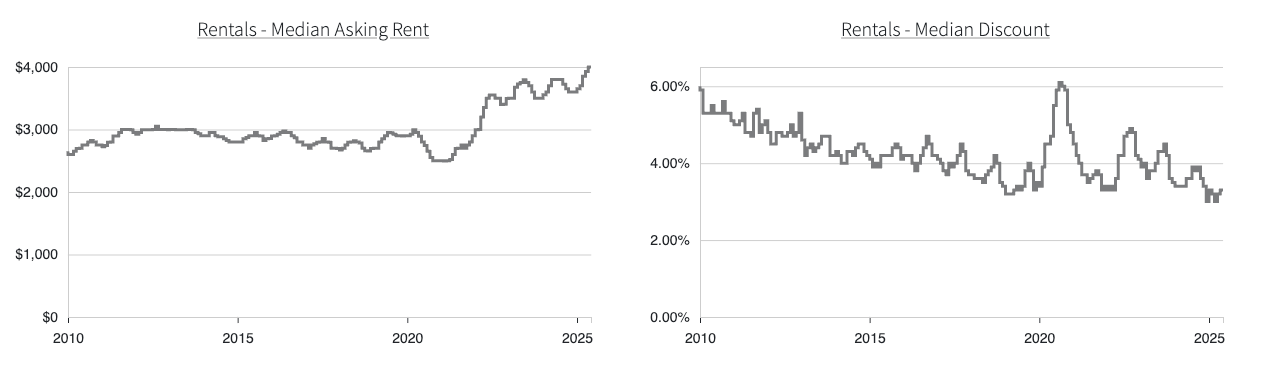

However, we did witness one big adjustment of demand relative to supply during covid—demand for housing fell, unlike in past building booms where it was outrun by supply. But it was so dramatic, so unmistakable, that New Yorkers should never forget what happens when supply grows relative to demand in a short period.

For those of us who stayed in the city, the rent deals were a shock. They began to resemble the dynamics of the 1903–1916 and 1920s booms. Prices fell sharply, concessions and free months piled up. It was a true renter’s market, and that all happened when the vacancy rate briefly shot up to 4.54%, compared to our current ~1.5%. Imagine what it would be like if we had sustained periods in the 5–8% window like we’ve had in the past!3

Some anecdata to put on top of this: in 2020 I took advantage of a low covid price to get a nice studio that rented for about $2,000 per month. That apartment’s rent is about double that price now. Any New Yorker with working eyes and a functional memory should wonder how we can replicate that scenario, which is clearly possible. Killing demand is not the way to do it—but we can outstrip demand with supply!

One last note. Sometimes I lay all this out, and a skeptical interlocutor will say something like, “But, Daniel, if increased supply drives prices down so much, then developers won’t build it, because they won’t be able to make a profit!”

I have two things to say to this:

Take that up with the historical record, which readily and often points in the other direction.

“Developers”, “landlords,” and “owners” are not one coherent block of people. These roles are often played by different people with different incentives. They don’t all move as one. Further: many of them can make money as supply increases, especially if the government does a good job of helping to shape the market! And even if someone is a “reckless speculator,” they still get housing built. Perhaps the most famous contemporary example is the Brooklyn Tower.

From “Left Hand Meet the Right Hand: New York’s Failure to Implement Transit-Oriented Development” by Jason Barr (January 2023).

Further: it is not that hard to find potential development sites today, many of them parking lots, in Manhattan alone.

Some reasons why, briefly: WW2 introduced citywide rent control that never really went away (it just transformed), in addition to spiking demand and introducing competition for raw materials. The city radically downzoned itself via the 1961 zoning resolution. The city’s population cratered by one million during the 1960s and 1970s as crime spiked, city revenue went into a near-death spiral, and residents left for suburbs. And it took several decades for our population to once again begin bumping against both our supply and our ability to increase it in the late 2000s, growing worse through the modern day.

For the contemporary covid-era vacancy rate, see:

2021 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey Selected Initial Findings, “The Rental Inventory and Vacancies The 2021: Net Rental Vacancy Rate,” NYC Department of Housing Preservation & Development, May 16, 2022, p.25.

Great read. Please read my latest post on housing advocacy:

https://substack.com/@nogoplus/note/p-176168396?r=6cyw21