What if housing supply didn't bring down rents?

Build it anyway! Maximum New York, baby

“Does adding housing supply put downward pressure on rent growth” is ultimately an empirical question, and the uncontroversial answer among economists and land use researchers is “yes.”1 It’s also the operating premise of much of my own writing.

But, for the sake of this essay, let’s say the answer was “no.” Let’s say that, no matter how much housing supply New York City added, downward pressure was not applied to rents (meaning they’re either slowed, plateaued, or lowered).2

Well—is it worth adding supply then? So much of the housing debate in New York City is focused on the price of rent specifically, so the merits of supply are often measured only relative to its effect on the price of rent. This is understandable: the price of rent is a central problem of New York today, and it has massive spillover effects in every arena of city life and urban agglomeration.

But this frame also ignores the other impacts that increased housing supply would have. So—should we build more housing supply, even if it wouldn’t move rents down?

Absolutely.

NYC Needs More Housing Supply Irrespective of Its Effect on Rent Price

1) More housing means accommodating more people

If NYC doesn’t add new housing supply, then it will not be able to accommodate more people.3 This doesn’t just mean welcoming people from outside NYC to the city, it also means welcoming people born here who grow into adults—will they be able to find a place to live near their family and friends? Many of them have a decent amount of money, but there simply aren’t enough units on the market to get, or they are so far away that they effectively sever the social fabric.

More housing means more ability to preserve existing social networks, more ability for people to live near their loved ones, and more ability for people to create their own communities:

And as they transformed the city, New Yorkers transformed themselves: they escaped pogroms to ply a trade, left farms for a new middle class, and fled the South to spark a renaissance in Harlem.4

Paradoxically (to some), new housing supply generally helps prevent displacement:

While new supply is associated with measures of gentrification, it has not been shown to heighten displacement of lower income households; and…The chains of moves resulting from new supply free up both for-sale and rented dwelling units that are then occupied by households across the income spectrum, and provide higher income households with alternatives to the older units for which they might otherwise outbid lower income residents.5

2) More people means more political power in the federal government

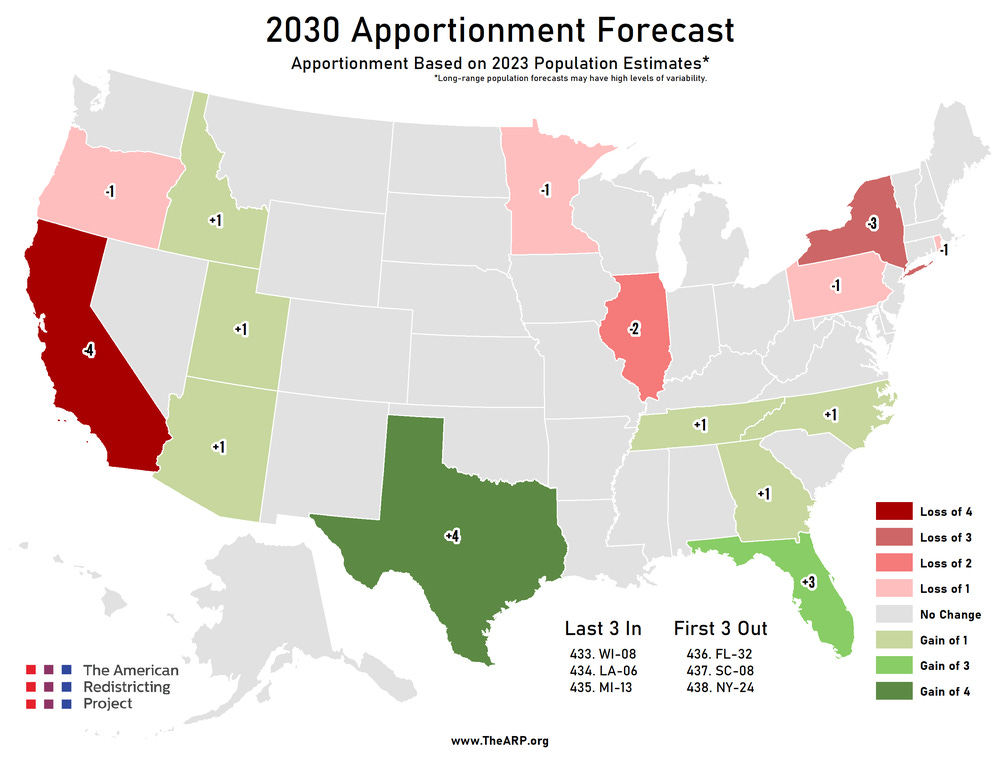

The amount of representatives a state has in the federal House of Representatives is determined by their population. New York used to be the most populous state, but its share of representatives in the House continues to slide census after census:

In 1960, the last time New York City comprehensively changed its land use policy, New York voters elected 9.5% of the House of Representatives. Today, New York elects only 6%, with recent population estimates suggesting New York will lose another two seats by 2030. This trend highlights a broader shift in New York City’s history, with the city growing more slowly than the country at large. The result is a city with less and less say in our nation’s capital.6

An inevitable consequence of opposing housing supply is disempowering New York City and State in federal politics, and empowering states like Texas and Florida. This is a policy consequence that cannot be ignored. If you live in New York and believe in its power to help drive the American future, you would do well to embrace housing supply.

Further: since presidential electoral college votes are determined by adding the number of federal representatives and the number of federal senators a state has, a declining amount of representatives means less electoral votes—and less say in who becomes president.7

(This same argument is also true for New York City’s political power in the state government—the more people the five boroughs have, the more representatives we get in the State Assembly and State Senate.)

Fighting housing supply in New York directly translates to this:

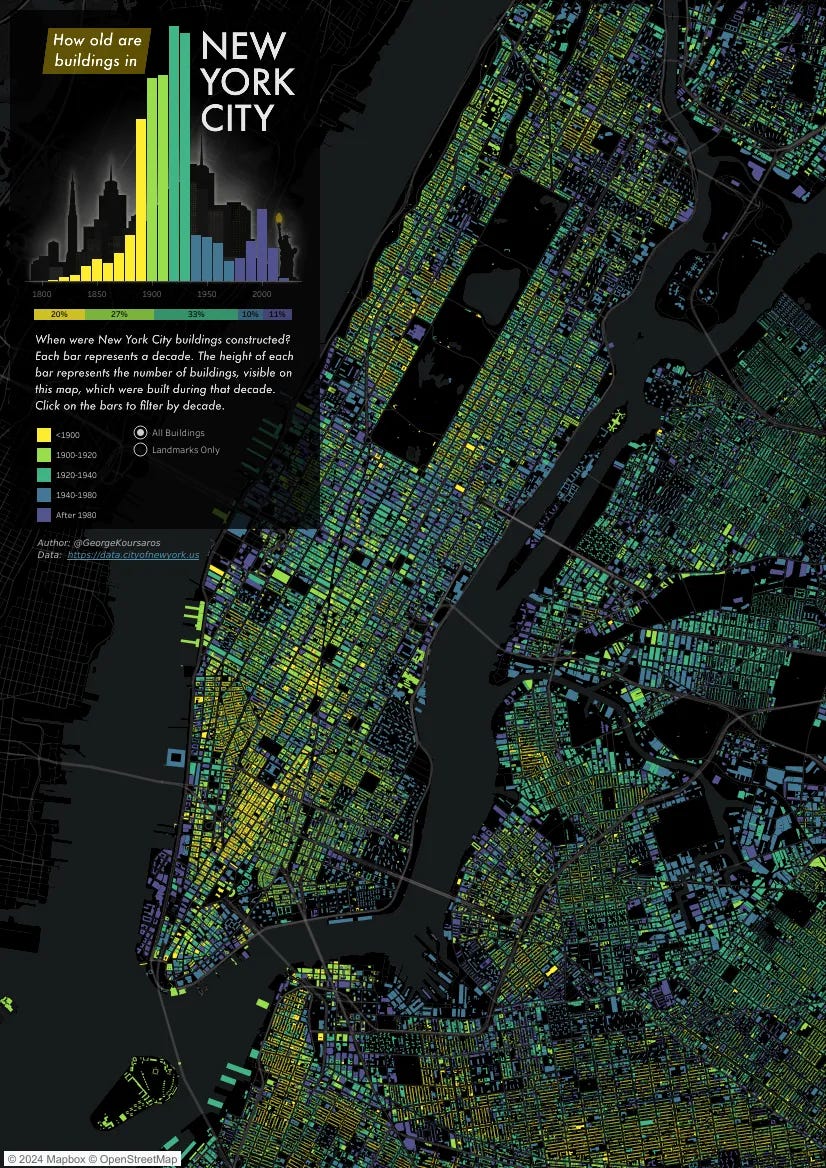

3) New York City’s apartment stock is extremely old, and new supply would allow New Yorkers to experience modern American living standards

“I have a washer and dryer in my unit, I enjoy centralized climate control instead of radiators, I have an elevator, my windows are large, my appliances are recent models.”

Many New Yorkers would say this describes “luxury apartments.” This is kind of true. Apartments that reflect the common standard of living elsewhere in America are luxury in New York City, because so few are permitted that they are relatively rare and sought after. In the same way that the easy and plentiful access most Americans have to food would reflect royal, almost obscene wealth in previous eras, modern apartments you’d find across America read as “luxury” here.

But they don’t have to remain “luxury.” They could just be “a regular apartment that reflects baseline expectations.”

But to do that we have to allow new apartments to be built at scale. We need supply.8

Most of NYC’s buildings are very old, and the vast majority of our building was in the distant past. ~71% of our residential buildings were built before 1951!9

The chart below breaks down all buildings like this:

Built before 1900: 20%

Built between 1900-1920: 27%

Built between 1920-1940: 33%

Built between 1940-1980: 10%

Built after 1980: 11%

Embrace supply, help do it right

When you zoom out and look at the full suite of effects of housing supply, I think it’s clear that we should embrace it at massive volume in New York City. That is, in fact, how we got the New York of today. It is how we defeated past housing shortages.

If we do not, we will continue to forfeit intact social fabric, political power, higher standards of living, and so much more. And that’s all before even considering new supply’s impact of the price of rent.

Of course many people point to worries about supply. They worry that new buildings aren’t as beautiful as past buildings. They worry about displacement. They worry about disruptive construction. They worry about infrastructure capacity. They conflate modern housing construction with Robert Moses and mid-century urban renewal. The list goes on.

I have two responses to these worries:

They don’t come from nowhere, and they respond to real things.

But the correct move is not to oppose supply. Opposing supply results in a set of tradeoffs I hope are unacceptable to most New Yorkers. The correct move is to join the policy process to help ensure that supply is added well.

Worried about ugly buildings? Join people who make beautiful ones. Etc. You are not powerless. Your options are not “build nothing, accept lower standards of living, and slide into political disempowerment” versus “build and watch everything you love be destroyed.” If you think those are your only two options—there is no good future for you, and you can only look forward to dystopia of some kind. And yet many people have convinced themselves of just such a thing!

Fortunately that is not your slate of options. You can choose: “Build well, mitigate downsides well, get higher standards of living, get more political power, and more.” You know, Excelsior. We’ve done this before. If you want to know what kind of housing to build, that’s a separate question, but I think an honest appraisal of New York’s political economy would say: unleash massive market-rate construction, and supplement it well with various government programs.

Final Note: Analogy to zoning and land use

When people talk about increasing housing supply, they often talk about zoning. Zoning is probably the single most important factor in getting new housing online, because it controls whether or not you’re allowed to build it in the first place. If you don’t have the zoned capacity to build something, it’s not happening.

But assuming you get the zoning, you have to consider construction codes, financing, and other factors. Those are worth thinking about too, as many people do.

Similarly, when we talk about housing supply, we often focus on its effects on rent prices. That is vital, and is the most immediately relevant things to most people. But there are other things worth considering too.

It is worth highlighting that increased housing supply is—surprisingly—much more worthwhile than merely better rents. Good news!

Supply Skepticism Revisited: What New Research Shows About the Impact of Supply on Affordability (2023) generally reflects the consensus understanding.

The 1920s construction boom would be very surprised.

You could argue that the existing housing stock could accommodate more people if they just doubled up—like instead of one person in a studio, two people should live there. But then you’re making an argument to constrain people’s ability to make choices about how to live, and arguing for a move toward overcrowding at least at the margin. If you’re proposing such a sweeping law as one that would require this, you might as well go in the other direction and enable housing supply.

“Letter from the Executive Director,” New York City Charter Revision Commission Preliminary Report (April 30, 2025), p.3

See the abstract of Supply Skepticism Revisited: What New Research Shows About the Impact of Supply on Affordability (2023). You can find a more casual explanation of the phenomenon in Noah Smiths “Yuppie Fishtanks.”

New York City Charter Revision Commission Preliminary Report (April 30, 2025), p.28

Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution: “The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.”

Simply gutting existing buildings will not be sufficient. First: if you try to completely redo the interior of a building to bring it up to modern standards, you will find that the law will try to stop you at many different junctures. Second, if your solution is only to gut new buildings at scale to bring them into the modern era, you will have to find someplace for all of those people to live—but we have too few vacancies in NYC! You’d need somewhere to put them…perhaps some new supply?

From Welcome to the FAR Dome: By How Much is Gotham Allowed to Grow?, the “Overbuilt Gotham” section:

“Many residential structures were completed before the 1961 codes, with 71% of the city’s residential buildings built before 1951.

So, if a developer is going to tear down an older structure to build a denser one, the allowable FAR needs to be sufficiently higher than the current one. However, we see a hurdle to new construction once we compare today’s maximum allowable FARs to the actual built FARs.

Currently, 39% of the city’s residential buildings are above their respective allowable FARs, and 63% are above or within 25%. In other words, for nearly two out of every three residential buildings, it is either impossible or uneconomic to tear the building down to increase housing availability.”

4. more housing development means a larger tax base and better funded public services! Not quite as relevant to NYC but I think very compelling to lots of smaller cities with shrinking tax revenues

Hello Maximum,

This reminded me of something I often find lacking in urbanist content. It seems to me American (Non-New York-based) Urbanists and Yimbys idolize Europe and Montreal, drone on and on about our lack of walkable cities, and never look to New York as an example for dense American urbanity. Do you think because this is because of what you describe in this piece? They think New York is perpetually too expensive to be replicable?

In my view, it's the rest of America which is too expensive to replicate going forward. We simply subsidize their car-centric lifestyles. Our high cost of housing is indicative of the fact you can make density massively, perhaps (as you suggest hypothetically) infinitely desirable.

Great piece, thanks.