2025: New York City's Electoral College Election

The city has one more shot to stem electoral college vote loss after the 2030 census

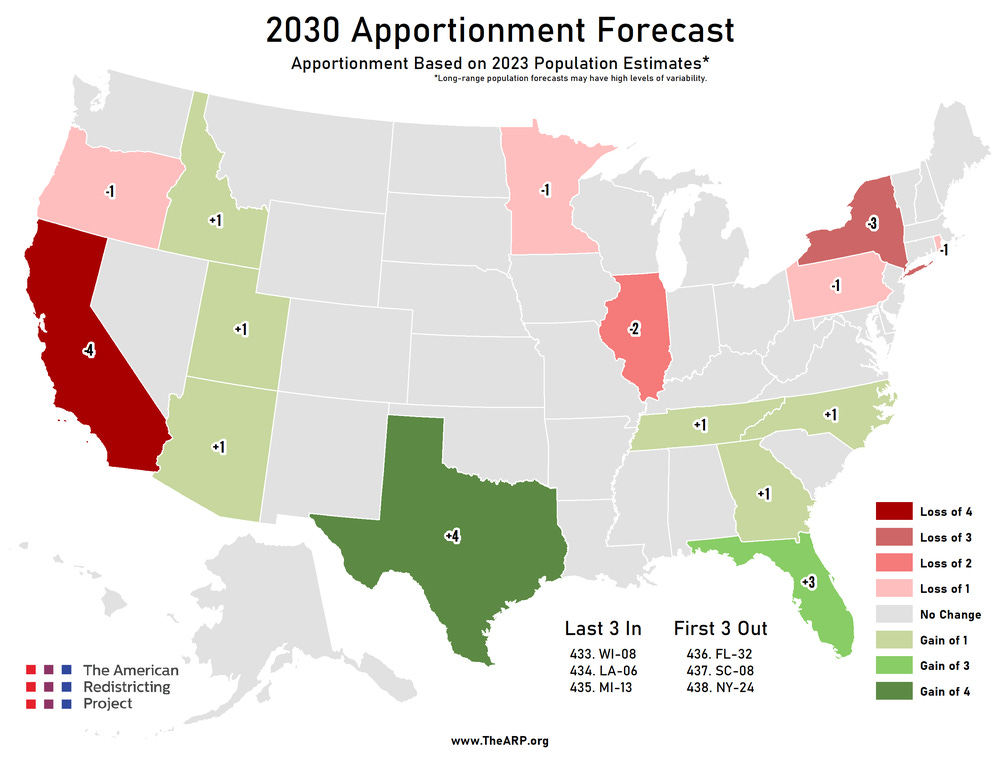

New York State is currently on track to hemorrhage relative population, federal representation, and electoral college votes to other states after the 2030 census.1 Why? Because those states build far more housing than New York: “TX/FL permit more multifamily units than CA/NY, and their apartment buildings are bigger.”2 This constant stream of supply keeps their cost of living down and attracts residents.

Housing costs, far more than other things like taxes, are the cause of New York’s relative population loss, especially for families: “The typical family that moves out of New York State saves 15 times more from lower housing costs than they do from lower taxes.”

The 2025 city elections are the last chance that New Yorkers have to select a government that can reverse this trend by legalizing and incentivizing the construction of vast amounts of housing supply. Why? Because the winners of the next city elections in 2029 won’t take their seats until 2030 (too late), and the state government—especially the legislature—does not yet show an appetite for action here. It’s the winners of the 2025 city elections, and that’s it.

The electoral college hinges on voting for housing supply

On December 5, 2024, the New York City Council passed Mayor Adams’ City of Yes for Housing Opportunity zoning text amendment, which is estimated to produce 80,000 units over the next decade. The reality is that New York City needs a plan for ten times that amount over the next decade, but City of Yes showed that at least some members of the city’s legislature are waking up to the direct connection between increasing housing supply and New York’s federal power.

City Council Member Carlina Rivera drew the connection when explaining her vote in favor of City of Yes: “…we are on track to lose additional seats in Congress after the next census because of out-migration.”

Still, the vote was 31-20 in a body that usually votes with near unanimity, and that was only after the council watered down the zoning proposal by about 20%. More housing supply is still a tough sell.

Housing supply’s toughest customer was Council Member Chris Marte, who stood out as the lone Manhattan representative to vote “no” on City of Yes—see the red district at the tip of Manhattan in the graphic above. When explaining his vote, he said the plan was a giveaway to real estate, and would destroy local communities with new market-rate housing that would sit empty at the same time as it drove up rents.3

To be frank, I found Marte’s remarks to be economically unsound, made-up, detached from cause and effect, and completely dismissive of the fact that New York City is in a desperate housing supply crunch that is sapping its political power on top of everything else. Even if most of his district really wanted a council member who voted “no” on City of Yes, they should want more than their current inadequate advocate.

Erik Engquist went line-by-line down Marte’s explanation of his City of Yes vote in yesterday’s The Real Deal. I encourage you to read the whole piece, but Engquist lays things plainly at the outset:

Just because Chris Marte was the only Manhattan City Council member to vote against City of Yes doesn’t make him wrong.

What makes him wrong is every single reason he cites for his vote.

I asked Marte’s primary challenger, Jess Coleman, what he thought of housing supply and the electoral college, as well as his opponent’s position on City of Yes. As it turns out, he’s on the same page as Marte’s colleagues in the Manhattan council delegation. Here are two questions I asked him via email, with his answers in full.

Q: Is electoral college vote loss currently an issue for you? Do you think it should be an issue for others? How large of an issue is it in the 2025 race, in your view?

A: The loss of electoral votes as a result of our housing crisis is a major issue we should take seriously, but not just as a political calculation. The electoral consequences of the housing crisis are simply a stark illustration of the broader hollowing out of our society that is caused by a politics of scarcity and protecting the status quo. The future will be won by cities and states that can build, innovate and adapt; if we fall behind, we won’t just lose elections. We’ll lose tax revenue, businesses will lose access to the best young talent, our cultural influence will wane. Human beings are the engine of our politics, our economy, and our culture. If we fail to meet people’s most basic needs (housing first and foremost) the consequences are truly limitless.

Q: Regarding electoral vote loss stemming from lack of housing supply, what would you say to your primary opponent who voted down City of Yes for Housing Opportunity?

A: If the vision of leaders like Councilmember Marte prevails—if we protect things like parking mandates over building three story buildings near subway stations in Queens—we as progressives have lost the future. It’s that simple. A new generation of New Yorkers is struggling to envision a future they can afford in this city. If we cannot speak to their needs, and cater only to the few, most fortunate New Yorkers for whom the status quo is working, nothing else will matter. City of Yes is an incredibly modest proposal aimed at the most urgent crisis facing our city—if we cannot support it, we have no chance of speaking to the growing body of voters desperate for leaders who will fight for them.

A note to New York City’s legislators, current and future

New York’s current mayor, Eric Adams, and many of his primary challengers, are throwing down big targets for city housing production.4 While the current and future mayors need to drive housing production, they are far ahead of the city council, which is the squeaky wheel in the system here. Any major land use decision, including zoning changes to permit more housing construction, must go through them. The “council problem” is exemplified by City of Yes’s difficulties getting legislative approval—even with a 20% reduction—despite its modest size and extremely drawn-out review process.

The 2025 city elections will be about many things, but I’m interested in council candidates going on the record as “for” or “against” losing electoral college votes, and doing what’s required to avoid a loss. The decisions they make immediately upon taking office, especially on land use, will directly impact that result. If they need inspiration, our city’s history readily provides it.

New York City has moved quickly in the past to permit new development and political change. We’ve built over 100k housing units in a single year. We self-financed the original subways, and built them over strong objections and adversarial circumstances. The city government of the past also knew that it was important to get big change through, and then be ready to iterate and amend it as needed. The current council doesn’t trust itself to do this…yet.

When asked about bold housing production, many council candidates will equivocate and try to bury the tradeoff they’re making by blaming their constituents for their own lack of courage. They will avoid the question of stemming electoral college loss by saying that developmental plans can’t be rushed, that neighborhoods need proper input, that they’re hearing “concerns from constituents,” and that we need to move more slowly to “get it right.” They will emphasize process over results, paperwork over execution, and unending public meetings whose attendees usually don’t represent the broad populace. The upshot: they will simply not approve any plan, and will not provide their own alternative that meets the moment. They are not interested in action. They are the newest generation of naysayers.

Often legislators are not brave (although some are!), and this lack of bravery means they do not execute plans quickly. This, in turn, means they do not see big things come to fruition within their council term, which means they cannot take credit for big wins.

So council members, current and future, take heart: if you are brave enough to accelerate New York City into the future by allowing it to grow, you will be able to claim the credit when 2030 rolls around. Not only will you save New York from political power loss, but the immense economic, cultural, familial, and all-around positive benefits of swiftly exiting the housing crisis will be unmistakably yours to claim.

But if the council cannot approve a plan for New York City to get ~one million homes, with rapid development beginning as soon as possible, they consign our state, our city, and their constituents to a massive looming loss of political power. And not because other states worked especially hard—but because New York State and New York City simply didn’t get out of their own way.

It’s time for New York City to build housing at historic levels

The 2030 census is just five years away. As a result of those population tabulations, states will receive their share of representatives in the House of Representatives, and with those their electoral college votes and sway on the national stage.

The 2025 New York City elections are the last chance the city will have before 2030 to pick a mayor and city council members who can reverse our projected loss of people and power. And because the Democratic candidates will most likely win in the November general contests, these consequential decisions will really be made in the June 2025 Democratic primaries—less than six months away.

This deserves emphasis: The future of the city and state until 2040, the next census opportunity, will likely be locked in in less than six months.

But New York City, when it leads, can do big things. It can build the housing it needs, including all the infrastructure that housing will need. Some critics will say something like “the low hanging development fruit has been picked.” This isn’t without merit. Building in many parts of New York City is harder today than it was in the past, partially because it’s just not greenfield development like the first time around. But we can be bold and visionary—and there is still plenty of low-hanging fruit: “Outside of Manhattan, 63% of all properties within one kilometer (1KM) of a subway have two stories or less, while 92% are three stories or less.”

I’m happy to assist any legislator, borough president, community board member, or government staffer who needs help developing their own plan to build housing.

New York State used to be the largest in the union, and carried 47 electoral college votes. Today we have 28, falling just under our total in 1812 when the state voted for the Federalist presidential candidate.

If we start selecting city councilors and mayors who truly champion growth, development, and opportunity for all, we can aim for 48.

Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution: “The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.”

Article 2, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution: “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress…”

The source of the data in the post is the Census Building Permits Survey.

“I represent neighborhoods like the Lower East Side in Chinatown, where unchecked market rate development has led to skyscrapers that sit empty, drive up speculation, and causes rent to sky rise and displace immigrant communities that have been rooted there for generations. The City of Yes is a yes to only the real estate developers.”

Eric Adams pushed City of Yes for Housing Opportunity, and recently announced another series of zoning changes, including The Manhattan Plan.

Mayoral hopeful Zellnor Myrie announced a plan for one million homes in New York City, 700k new and 300k preserved.

I became aware of, and very much in opposition to Marte when I looked up his comments about The City of Yes, and his previous opposition to new construction. He has actively criticized and campaigned against new housing development, citing things like “environmental racism” as to why.

He is unashamedly working in the interests of long time residents against the interests of the city and more recent residents as a whole. I honestly find his opposition to housing (as his apparent core beliefs should definitely be pro-development) as disgusting.

I also happened to move into his district 4-ish months ago and have already registered my permanent address in his district. What can I do to (in terms of low-effort things like voting or registering to vote in a specific primary - I have a lot of other things in life going on) reduce his chances of reelection in 2025? I take it as a given that voting Republican or third party is not a meaningful action.

I love the ambition here! Before now I hadn't considered electoral votes to be a an argument in favor of more housing, but I'm on board with the premise