NYC's Median Rent is ~$1.6k, and How That is Even Possible

Quick notes on why 75% of New Yorkers pay less than $2,400 for their apartments, why you've thought otherwise until right now, and why you can't seem to find those good deals

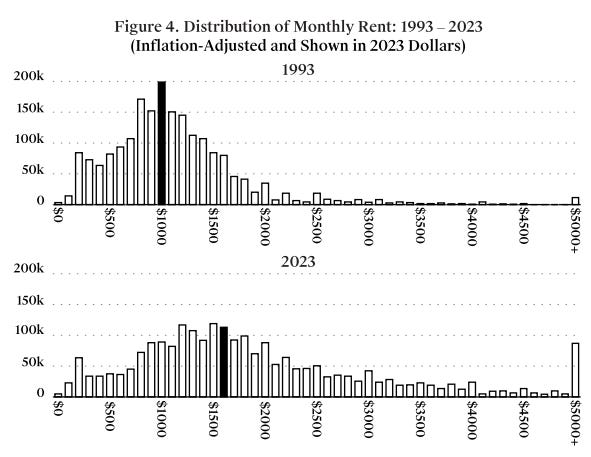

I recently tweeted the image below from NYC’s 2023 Housing and Vacancy Survey:

Since the tweet is now getting some legs, I have a few more details I’d like to add as people try to wrap their heads around this information. To many, it is unbelievable, and it flies in the face of what they think they know. But I’ll ask them this: did you ever actually look up the median rent that was paid (not the median rent that was listed for available units on Streeteasy, and not headlines about the most expensive new places)? It’s been there the whole time.

This isn’t a comprehensive post, just some quick examples of the nuance that exists. Enjoy digging further!

Most of the rental housing in NYC is non-market.

You can read more about that here, but here’s a breakdown of our rental stock at the moment:

[Note added after publication: “market rentals” does not legally mean “charge whatever one wants,” especially after the passage of Good Cause in 2024. Even “market-rate” units have price controls, although the exact way those play out is complicated.]

The median rent for an apartment in NYC is ~$1,650 across about 2.3 million rental units.

Here’s the breakdown:1

26% (604,000) have rents above $2,400 (74% are below $2,400)

24% (554,000) have rents between $1,650 and $2,400

25% (578,000) have rents between $1,100 and $1,650

25% (586,000) have rents below $1,100

About 250,000 of these are rent stabilized

130,000 are in public housing (NYCHA)

180,000 are market rate

NYC’s rent regulation system and other laws hold rents far below market equilibrium, which creates bad problems overall.

The effects of this are not immediately obvious, and depend on other factors. But in NYC’s specific context, where we have a severe supply shortage and a vacancy rate scraping 1%, this is the dynamic that plays out in two big ways:

1) People get trapped:

Person A gets an apartment that is a “good deal,” that comes with restrictions on how fast rent can rise.

Person A is more than usually unwilling to leave that apartment.

Time passes, and rents around Person A continue to rise as people without good deals bid against each other to try to find someplace to live.

Person A adjusts their life and budget to their good deal. They stay there.

Person A now perhaps wants to move, and looks around at the available options. Person A realizes they cannot afford those options, or there are so few they can afford, that they can’t actually get the apartment because of competition.

Person A is now trapped, and cannot move to get a bigger apartment for a family, or whatever else they need. They can’t even make a lateral move to a similar apartment.

Everyone else also can’t get access to Person A’s apartment, even though Person A would love to leave, and continue to bid against each other.

1A) The trapped people (and others) create a low-pressure bubble that increases market pressure on the remaining rental stock

Much of NYC’s rental housing stock is isolated by law from the attempts of the market to equalized price according to supply and demand. As a result, the relatively smaller portion of the rental stock that is market-rate is subject to even more pressure as people just looking around for a place to live bid against each other—since they’re disproportionately locked out of even looking at the many places inhabited by trapped/other people. NYC might have 2.3 million rental units, but you actually can’t rent that many of them just by walking up and offering to pay.

As I tweeted yesterday:

Part of how to square this: many people think "I don't see any listings for all these cheap apartments!" That is because they are not listed, nor are they available on the market (or they are not happily, transparently on the market, or they are very far away from core Manhattan such that your search settings never include them). This is a graph of what people *pay*, not a graph of what is potentially available. For example: New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) units have cheap rent, but you won't find those available for just anyone.

Similar dynamics for rent-regulated apartments that are inherited, or otherwise don't actually surface to the market for one reason or another.

If you have only ever existed in the market-rate housing world with rents of $2k+, there is a whole other housing world in NYC--and it's most of the housing world.

2) People with good deals are subsidized by their peers paying market rents, and neither party is typically aware of how this works out

Generally speaking, if you have a “good deal” on a rent regulated apartment, there’s a good chance that your rent is not enough to cover the operating expenses of that apartment. And there’s a good chance you’re in a larger, multi-unit building.

So if your rent cannot cover its own expenses, guess where the building owner will reasonably try to make up the difference? In the rent of the market-rate apartments that your friends and neighbors rent.

In a severe supply shortage like the one NYC has, there is no free lunch. If you have an apartment that doesn’t cover its own expenses (many such cases), I have two things to say to you: (1) enjoy it! You didn’t design our rent regulation system, and you didn’t cause NYC’s housing shortage. I think you should feel fine about taking advantage of the deal, but (2) understand the economics of it all, and that you likely might be cross-subsidized by people whose rents your good deal inflates. The only way out of this zero-sum, musical chairs housing shortage is to build far more supply.

But you might wonder: why not just give everyone a good deal, and freeze/regulate the rent across the board? That way no one’s rent would put extra pressure on anyone else’s rent. My general response to that: show me the spreadsheet where the math works out. There are many ways to achieve more affordability in NYC—massive housing supply being the key to any of them—but across-the-board rent regulation would probably make a worse situation…much worse.

This gets more complicated by the fact that our rent regulated units are distributed unevenly across buildings and across the city.

2A) A building finance scenario

Consider the following two buildings:2

Building A: 10 units: 5 market rate, 5 stabilized; breaks even, makes $0 when building expenses are paid for.

Building B: 10 units: 10 stabilized; breaks even, makes $0 when building expenses are paid for.

Now, let’s say a principal piece of the building needs an expensive repair, like the boiler or heating system. How are they going to get enough money to do that, or how will they borrow enough money to do that (considering that loans are principally based on rent rolls and net operating income)?

Under a rent freeze, Building A could raise the rent on its market-rate units to cover the expense, or the cost of the loan to cover the expense. But Building B? It loses money. Maybe it can get a loan, but the cost of that loan eats directly into building savings and displaces money that could be spent on other things.

This is a simplified scenario, but it highlights two points:

There is not one kind of “rent stabilized building.” The apartments are scattered, in different ratios, across different parts of the city in buildings of wildly differing states of repair and potential revenue. And yet, these units all get the same price control put on them, even though the buildings they’re in can’t tolerate the same kinds of price control.

Under a rent freeze, market-rate units pick up the financial slack for emergencies and other costs. There is no such thing as a “rent freeze,” but there is such a thing as a “rent freeze for me, rent increase for thee.”

The fundamentals of building finance come down to one thing: someone must pay to keep buildings in good repair. It does not matter who owns them: a non-profit, a for-profit, or the government.

[Note added after publication: if you wonder “Is this a problem? People will just leave if landlords raise rent to compensate for apartments that don’t support their own costs,” see my response here.

Put another way: when inflation (input cost increases) happens, restaurants, manufacturers, and other places raise their prices. No one blinks an eye at this reality. They do not say “that doesn’t happen. Otherwise they would have just raised their prices before without the inflation cost increases, and just pocketed the extra profit.” People will deny the reality of this phenomenon in housing, however. I’m not saying it happens all the time, everywhere—it is context dependent, just like inflation price adjustments—but it is absolutely a real phenomenon. When demand for a good like NYC housing is inelastic, and supply is sharply constrained, price increases don’t work the way one might initially think.

Put a final way: you can check this if you really want to. Talk to property owners of rent-regulated buildings, large and small. Look at balance sheets. Read what they write. Follow publications that focus on real estate. Follow good people on LinkedIn. If your only information comes from renters, well, ask yourself this: what do you think of people whose information only seems to come from owners?]

2B) Nuance! Preferential Rents! Always examine local context!

Keeping in mind what I said above, which is most often true, the following phenomenon can exist alongside it:

Some rent-regulated units have a legal maximum rent they’re allowed to charge. But since they can’t get anyone to pay that maximum, they have to lower their rent below that level—these are “preferential rents.”

Supply and demand are a hell of a drug, and the dynamics of New York City’s housing market are full of surprises.

Housing abundance advocates should take a hard look at the actual rent paid across the five boroughs

Although the prices of new rentals in highly desirable locations make headlines, those are not nearly what most people are paying in New York. That doesn’t mean people aren’t rent burdened though, and it doesn’t mean the situation is good.

Those high prices are the result of the way in which bad laws have structured our housing market. Most of the rental stock does not respond to market signals very well, and instead exists within a two-pressure front (yet another way of dividing housing into two problems):

Low pressure front: rents are held below equilibrium. This might be good in the short term for an individual, but it can create long-term financial problems for the building, increase cost pressure on other units, it can trap the individual, and it can prevent others who could greatly benefit from the apartment from getting it because the trapped person cannot move, even if they want to.

High pressure front: market rate units are even more competitive than they otherwise would be in a majority-market rental stock. Since many NYC apartments are effectively out of circulation for the general population, those who are looking to rent an apartment have a smaller pool to look at, and bid against each other more aggressively than ever.

Thankfully, we do know the cornerstone solution to this mess—supply. Massive amounts of it, with all kinds of housing. But especially market-rate housing. Paradoxically to some, the more market-rate housing you have, the more the competitive pressure moves from the tenant side (who can pay more) to the owner side (who can give the best deal). You can’t just rearrange the affordability deck chairs with price ceilings—this is a housing supply Titanic.

See 2023 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey Selected Initial Findings, p. 17 for all of these numbers.

There’s always a flavor of “screw the renters” whenever I see a piece line this. There’s the assumption that renting is supposed to be a temporary state that one is only in until such time as they can purchase a home. It is assumed that renters are transient. It is also assumed that “market” rents are somehow the objective and the only way for capital to get their appropriate level of return.

What is “market” rent? Market rent is the every damn penny a landlord can charge without a unit remaining vacant. It has no relationship to the level of expenses. Further, in a situation where some units are stabilized, a landlord does not say “I had an unusual expense, so I have to raise the rent on everybody else.” If the landlord could have charged more *the landlord would have charged more to begin with*.

Besides, over the last fifty years, NYC buildings with rentals have not been owned so much for operating profits; it’s been for capital appreciation.

Build more units? Yes. Replace late-in-life buildings with larger structures? Yeah.

But do not destroy the kind of community that develops from apartments that people can spend a serious part of the rest of their lives living in.

This is excellent analysis. I did not realize that the median rent was so low. No one who enjoys below market rents is complaining that the rent is too high. So without this type of analysis, one can readily have a lopsided view of the situation. Thanks Daniel!