How I'm Voting for Mayor in NYC's Democratic Primary

1. Tilson // 2. Myrie // 3. Adams // 4. Lander* // 5. Cuomo // (X) Not Mamdani

➡️ Read the follow-up to this post here, published one week after this one.

If you’ve read the subtitle and already feel gripped by a need to know my stance on Cuomo vs. Mamdani specifically, skip to the end! But I recommend reading from the top.

What informs how I vote?

While I have positions on many municipal issues, and care about all of them, here are the top eight considerations I’m using to inform my vote.

Rapidly increasing housing supply is my principal policy issue. Housing policy directly affects almost every other policy area, and if you get it wrong, everything else will always be compromised. And while many candidates now notionally agree that we need more housing (progress!), there are better and worse ways of working toward this goal.

Public order must be maintained and prioritized. If anti-social behavior (open drug use, running red lights, speeding, retail theft, public employees not following city laws, etc) is allowed in public spaces, those spaces will be used less by the public. This amounts to a privatization of public space for the few who care for it the least, at the expense of families, children, and the disabled foremost. But beyond those groups, everyone deserves a beautiful, orderly public realm that is funded by their tax dollars:

Many people online get locked into a diminished version of this discussion—it becomes about authoritarian police state surveillance versus anarchy. If someone tries to pull you in that direction, tell them they're doing it, and that this is a false dichotomy.

Public order can coexist with liberty and fairness—in fact, I think public order is the best way to achieve both of those things. The public deserves temples, beauty, comfort, and security.

Education spending must be brought into line with educational outcomes, and student achievement and opportunity must be the primary metric by which the city education system is judged. The Department of Education takes the lion’s share of the city budget, and there is no close second-place competitor. New York City spends more per pupil than anywhere else in the country, and yet our results are middling at best, even as the city school system does possess bright spots. The next mayor must be frank about not Goodharting the city budget in general, but especially education spending.

Good government operations, which include policy prioritization as well as selecting the many appointees who will be in charge of implementing them. Like housing, this permeates everything a mayor does. If they cannot manage a municipal corporation of ~300k employees, or pivot hard and effectively if the federal government cuts billions in funding overnight, it doesn’t matter if they have the right ideas.

The final two candidates on the ballot will very likely be Andrew Cuomo and Zohran Mamdani. I have many esteemed friends who will not be ranking either of these candidates. But I want to have my voter’s thumb on the scale when it comes down to those two, and I come down firmly, without hesitation, on Cuomo’s side.

Voting is a pragmatic exercise of raw political power, and a signaling exercise. I will be using my ranked ballot to achieve both of these things. My rankings are not purely in the order of who I think is best, or who is likely to win.

New York City should move in the direction of the sensible seventy, and should jettison politicians who play to the illiberal fringes of both the left and the right. The Democratic Party in particular, since it dominates the city, must learn this lesson (but hasn’t quite yet). New Yorkers and Americans tend to reject liberal candidates who take too many cues from the illiberal, degrowth, anti-market left. I mean this descriptively here.

The market and government are both needed for a free society with high standards of living, and are inseparable. Each has a vital role to play, and any candidate that denigrates either of those two components will get a tough hearing from me. The dynamism and innovation of the market move us forward, the wise restraint of law keeps that movement fair and preserves equality before the law. I believe in a capitalist system with a robust government support system around it.

My ranked order for the Democratic mayoral primary:

New York City uses ranked choice voting in primary elections, so you may select up to five candidates on your ballot. I will be using all five spots. Informed by my eight points above, my ranked slate is:

Whitney Tilson—Tilson is the only candidate taking education reform seriously in his campaign, and he notes exactly how we both overspend and underachieve. Further: he strikes sensible notes on transit, public order, and housing, and is probably the most broadly aligned with the New York populace writ large. When the mayoral candidates were asked if they’d ever voted for a Republican, he also was not afraid to admit that he voted for Michael Bloomberg (then a Republican) for mayor during the last mayoral debate—this is the kind of frank, commonsense attitude that New York’s politics need. You are not a bad Democrat if you voted for NYC’s most popular, effective modern mayor, especially one that most of the mayoral candidates praise privately and promise to emulate in key respects! For all of these reasons and more, I agree with Josh Barro’s endorsement. If I could wave a magic wand, we’d get Mayor Tilson.

Zellnor Myrie—he was the first candidate to announce a bold housing supply plan for one million homes (mostly new, some preserved) in the next ten years. It is not pie-in-the-sky, even though some details need to be filled in, and it is the only plan fully appropriate for the scope of our housing supply crisis. He deserves massive credit for throwing the marker down, and pushing the other candidates in the race to coalesce around the more “realistic” figure of 500k homes in the next decade. I have sharp disagreements with him on a variety of positions, but he nailed New York City’s top issue and helped move the rhetoric productively forward.

Adrienne Adams—she has demonstrated an atypical willingness among the elected class to push for more housing in New York City, most obviously by her support for City of Yes for Housing Opportunity. She was the head of the City Council at a time when—due to Mayor Adams’ legal troubles and many council members’ unwillingness to do big upzonings—the council could have kicked the housing can down the road without too much blowback. She did not do that, and she deserves firm recognition for it. However, I don’t otherwise think she would be an especially good manager, that she would push for ever more bold housing targets, or that she would address issues of public order and safety that well.

Brad Lander*—he is on this list because I believe he would perform somewhere between Bill de Blasio and Eric Adams at their best, but I have severe disagreements with him on a variety of issues, and his recent cross-endorsement of Zohran Mamdani shows (in my view) a severe lack of perspective, and an (*)almost disqualifying affinity for the illiberal left part of city politics. But I would vote for someone who is not that great, but who would be historically near-average as a city executive. His experience as comptroller (I quote several of his reports later in this piece) and a city council member mean he has a grip on how the government works, and that’s important, I just don’t think he would turn that knowledge in productive directions the way that New York City needs.

Andrew Cuomo—as many others have noted (here, here, or here, for example), Cuomo has committed some egregious policy and personal errors. He deserves full scrutiny for all of them, and I excuse none of them. However, he is very likely one of the two candidates who will be left standing after ranked choice voting operates, and I think he is unambiguously better than the alternative.

I am anti-endorsing Zohran Mamdani. While he is clearly smart, energizing to some, and has tipped his hat to many pro-urbanist, abundance-minded people, many of his basic policy proposals are cartoonishly bad, and he has aired illiberal tendencies of executive overreach with his non-stop promises to trample the statutory independence of the Rent Guidelines Board.

I’ll now explain my anti-endorsement of Mamdani in some more detail.

Why I will not vote for Zohran Mamdani

In a certain way of thinking, the difference between Cuomo and Mamdani is like the difference between 1 and 10—relatively small, but unambiguous, with no doubt as to which is higher or lower, even though both are pretty small when you’re looking for a 100.

My problems with Mamdani’s policy proposals can be boiled down to these points:

Misunderstanding the political economy of housing in New York City and State to the extent of policy flat-eartherism. Advocates of social housing should be disappointed that their views are being represented by such an inadequate advocate.

Cartoonish financial projections that would balloon city debt to unsustainable levels, even if he could get the relevant state law changes likely needed to take out that debt.

Not taking public order seriously, and proposing things that defy common sense.

Mamdani gets the political economy of housing in New York exactly backwards.

New York City has gotten essentially all of its housing, past and present, from private builders charging market rents, facilitated by city and state financial policy, and there is no reason to expect that the massive structural path dependencies making this the case have changed. The role of market-rate housing is not just central, it is imperative. Understanding this is a real litmus test—the facts are very clear. And although Mamdani gave a small nod to this fact in his News York Times mayoral profile, his policy platform does the opposite:

We can’t afford to wait for the private sector to solve this crisis. Zohran will triple the City’s production of publicly subsidized, permanently affordable, union-built, rent-stabilized homes, constructing 200,000 new units over the next 10 years.

“Publicly subsidized, permanently affordable, union-built, rent-stabilized…” This is blue tape, pure and simple, and it is more of the kind New York is already tightly bound by, that already strangles the provision of almost any major public good or housing. Are the intentions good? Yes. Do we know where good intentions lead? Also yes.

I can’t really put this mildly: the private sector has not been allowed to solve this because of antiquated land use laws and a mountain of procedural hurdles, to say nothing of sub-optimal finance policy. The 1961 zoning resolution, SEQR/CEQR, uneven property tax policy, subpar building codes, and more have stuffed the housing production gears full of sand. Mamdani not only denies the throttling of private builders, he operates under the assumption that blue tape will allow faster building, and that the city government will be able to accomplish this.

This is attempted mayoral Munchausen by proxy. Bad law and procedure have smothered private production, and Mamdani insists that the solution is, therefore, more procedure and getting away from private production. Even the rent regulation laws that he wants to expand explicitly note that their aim is to be a bridge back to a market-based housing system.

In the 1920s housing crisis, where vacancy rates fell below 1%, the state legislature and Governor Al Smith passed a grand bargain that unlocked housing production and solved the supply problem: it exchanged rent control of the existing housing stock for generous tax abatements for any new buildings (which would also not have price controls placed on them). The result was the largest housing boom in city history, and we are all better off having those units today. These were provided almost entirely by private builders.

But do note: the government had a role to play! In the 1920s, the costs of construction and post-WW1 inflation made housing production very expensive. Among other things, builders were worried that as soon as they built housing with those more expensive costs, post-war inflation would abate, and then they would be left going bankrupt as others took advantage of lower prices to build more cheaply and undercut them with rent prices. The market was nervous, and stalled. The state government broke this logjam with tax abatements that guaranteed more competitive building.1

Finally: I believe that the government has a vital role to play in providing housing for the bottom and some of the middle of the income distribution, where the market has never really done a great job by the lights of New York City’s residents. In the 1920s, we got the first notable experiments in this regard—like the limited-profit developments of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, completed in 1924 pursuant to Chapter 658 of the Laws of 1922.2 These kinds of experiments are great, and laid the groundwork and inspiration for other similar attempts throughout the twentieth century, more of which I hope to see going forward. But one thing did not change: the market and private builders were still the workhorse of housing production. And further: these experiments do not work well if they operate in a context of housing supply scarcity. One cannot ignore these central facts.

Mamdani’s housing targets are low compared to the other candidates, and are simply inadequate.

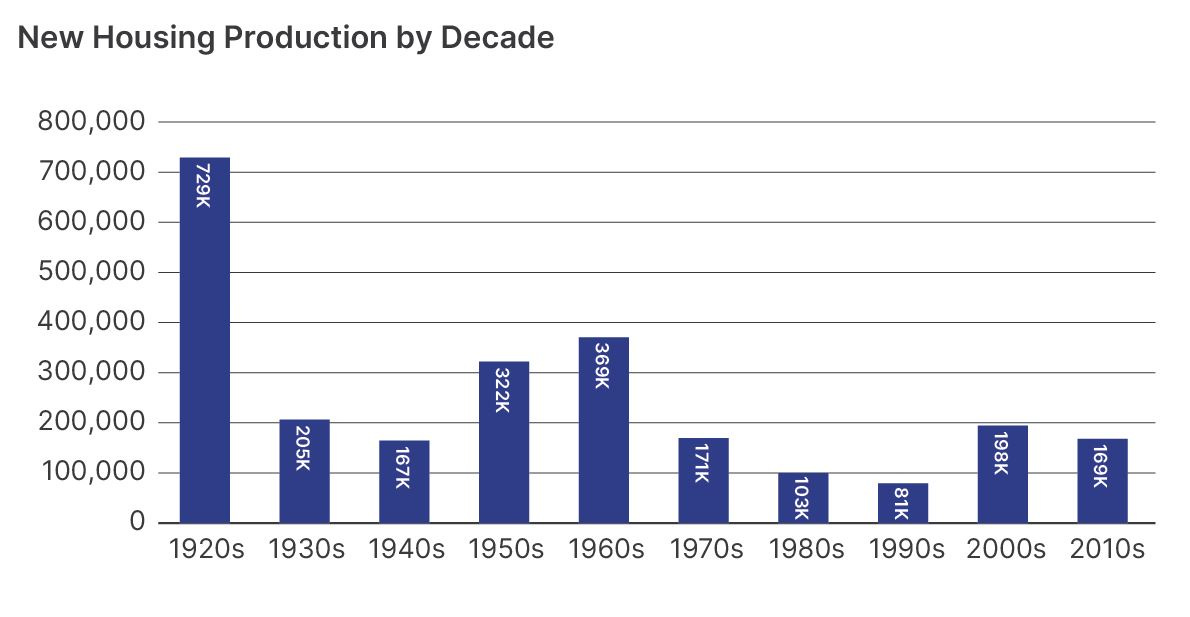

Most candidates have coalesced around “500,000 new units within a decade.” Mamdani trails them all dramatically, proposing only 200,000 new units. He wants to aim for the 2000s level of production, the others want to get closer to the 1920s (Myrie wants to set a record).

His financial projections don’t add up, and his debt proposal for the city is wildly irresponsible.

Mamdani proposes funding his 200,000 housing units with city debt (emphasis added):

“Zohran will allocate $70 billion new capital dollars in the City’s Ten-Year Capital Plan to create new affordable housing, raised on the municipal bond market. This is on top of the about $30 billion the City is already planning to spend, making our total investment $100 billion.”

Let us put aside the financial issue of whether I believe the city government could achieve that many housing units with that amount of money on that timeline (I do not).

Let’s just consider how much new debt he is proposing the city take out, relative to current debt levels. Currently, the city has a debt limit of about $135-140 billion, which is set in the New York State Constitution as a function of the full value of property within the city (article 8, section 4(c)). The city can currently issue about $28 billion more in debt if it wanted to, for all of its capital needs (see table below).

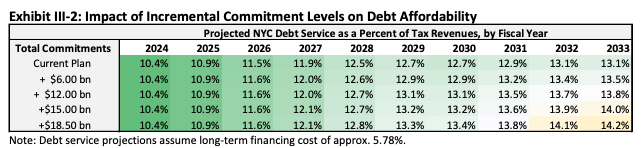

So how do we know exactly how much $70 billion in new debt would fit into the picture above? The comptroller’s office did a debt affordability study in 2024 that examined how $18.5 billion more in debt would affect the city budget over 10 years. City debt affordability is defined as debt payments taking up 15% of the city tax revenue or less. Here is how that study worked out, with +$18.5 billion pushing the city right to the limit of debt affordability by the end of the decade in 2033:

If that’s what an extra $18.5 billion does, what would an extra $70 billion do—assuming the city would be permitted by state law to take it out in the first place, and assuming it wouldn’t crowd out other forecasted capital commitments? And what if unforeseen events depress future tax collection or city property values, which contract the city’s ability to take out and manage debt? What if—hypothetically—the city were in an adversarial relationship with another level of government that restricted previously counted-on dollars?

Even if Mamdani’s debt plan worked out perfectly, and $70 billion could successfully be deployed to get 200,000 new housing units, it would be terrible. It would put the city over the edge on debt affordability and crowd out other items in the budget as debt payments ballooned, leave little cushion to address contingencies, and—here’s the kicker—we could get more housing without a debt explosion by replicated policy that is similar to the 1920s. There are better options sitting in plain sight.

Those who remember, or have studied, the city fiscal crisis of 1975 will reject Mamdani’s proposal out of hand.

Promising a rent freeze on mayoral authority is a promise of illegal executive overreach

Pursuant to city (and state) law, the Rent Guidelines Board sets the rate by which one- and two-year leases may change in rent regulated apartments (the “rent guidelines”), which account for about half of New York City’s rental stock (market-rate units are a minority of the rental stock).

Also pursuant to city and state law: the RGB must consider a variety of factors when determining the rent guidelines it sets forth. Per § 26-510 of the New York City Administrative Code, the RGB:

…shall consider, among other things (1) the economic condition of the residential real estate industry in the affected area including such factors as the prevailing and projected (i) real estate taxes and sewer and water rates, (ii) gross operating maintenance costs (including insurance rates, governmental fees, cost of fuel and labor costs), (iii) costs and availability of financing (including effective rates of interest), (iv) over-all supply of housing accommodations and over-all vacancy rates, (2) relevant data from the current and projected cost of living indices for the affected area, (3) such other data as may be made available to it.

The RGB is also required to publish the research upon which they base their rent guidelines, which you can find here.

The basic idea: they must balance tenant needs for lower rents, with the reality that buildings have costs that rents pay. Pursuant to law, they cannot just set the rent guidelines however they like. They must be grounded in an analysis that balances multiple factors.

So: what are we to make a mayoral candidate promising a rent freeze when he is mayor? Again, pursuant to city law, the RGB does not set rates at the direction of the mayor, even though the mayor appoints each member. You might not like it, but the RGB is an independent board with a job bound by city and state statute.

A mayor who promises to direct the RGB is promising to violate the law, and commit illegal executive overreach against a (nominally) independent board that is law-bound to data. There is no getting around this. Many Mamdani supporters should recall if there’s any point in time where they were advocating that people vote against a candidate for a government executive office for fear that they would abuse the powers of their office and trample the independence of other parts of government. I’m sure they can recall if they try.

Of course, Mamdani’s response to this is that the mayor really controls the RGB behind the scenes (via threats and soft power, which is true to varying degrees), so his plan is OK. Well—no. It is still the same legal violation, and the same illegal executive overreach. It doesn’t matter if others have done the same, or if Bill de Blasio seemingly admitted via Twitter/X that he committed that illegal overreach too in support of Mamdani’s position.

Interestingly, Mamdani and Andrew Cuomo went back and forth on this in the second Democratic primary debate. When asked if they would pursue a rent freeze, Cuomo correctly responded that the mayor cannot control that:

Cuomo: “Would I vote for a rent freeze this year? I’d leave it to the rent guidelines board.”

Mamdani: “Who controls them? The mayor.”

Cuomo: “We appoint them, the law controls them.”

Cuomo was objectively right about the law here, and Mamdani was wrong. What’s worse: Mamdani does not seem to care that one of his central campaign promises is a promise of blatant, illegal executive overreach. Many other candidates have also “called for a rent freeze,” but Mr. Mamdani is the only one I have seen who reaffirms his stance even when confronted with the law on the public record. This promise of future lawlessness simply cannot be taken lightly.

A rent freeze is also bad policy

As I mentioned above, the Rent Guidelines Board is required by law to publish the data upon which it bases its rent guidelines. Many people think the data could be improved in many ways, myself included, but that’s not the issue here.

The issue: there is no such thing as a uniform rent stabilization system for New York City. It is several systems stacked in a trench coat, enacted at different times across the twentieth century. The result: wildly different kinds of buildings, with differing amounts of rent stabilized units in them, all get the same RGB rate. Practically speaking, it is impossible for the RGB to freeze the rent in the modern day without sending many buildings into bankruptcy or wildly depleting their cash reserves—exacerbating the problems their tenants already face.

Consider the following two buildings:

Building A: 10 units: 5 market rate, 5 stabilized; breaks even, makes $0 when building expenses are paid for.

Building B: 10 units: 10 stabilized; breaks even, makes $0 when building expenses are paid for.

Now, let’s say a principal piece of the building needs an expensive repair, like the boiler or heating system. How are they going to get enough money to do that, or how will they borrow enough money to do that (considering that loans are principally based on rent rolls and net operating income)?

Under a rent freeze, Building A could raise the rent on its market-rate units to cover the expense, or the cost of the loan to cover the expense. But Building B? It loses money. Maybe it can get a loan, but the cost of that loan eats directly into building savings and displaces money that could be spent on other things.

This is a simplified scenario, but it highlights two points:

There is not one kind of “rent stabilized building.” The apartments are scattered, in different ratios, across different parts of the city in buildings of wildly differing states of repair and potential revenue. And yet, these units all get the same price control put on them, even though the buildings they’re in can’t tolerate the same kinds of price control.

Under a rent freeze, market-rate units pick up the financial slack for emergencies and other costs. There is no such thing as a “rent freeze,” but there is such a thing as a “rent freeze for me, rent increase for thee.”

The fundamentals of building finance come down to one thing: someone must pay to keep buildings in good repair. It does not matter who owns them: a non-profit, a for-profit, or the government. And a rent freeze, right now, would be terrible policy, especially for older buildings in the Bronx that tend to serve the populations rent freeze advocates claim to be helping the most.

For what it’s worth, I do not think our current rent regulation system can possibly work well (even though I admire many of the members of the RGB, and hold them in high esteem). They are put into an impossible situation: setting one rate for wildly different sets of buildings. They can either freeze the rate and doom some buildings, or raise the rate to save them, but make other tenants angry at what generally would amount to a barely-above-inflation increase. Any candidate who would propose extending this system does not understand how it is set up to fail.

He is not serious about maintaining a pleasant, orderly environment in the subways, and disrespects the homeless population in the process.

As part of his plan to address safety in the subway, and to help the homeless population, Mamdani proposes to entrench that population in the subway itself by establishing treatment centers:

Transforming vacant commercial units in our stations

There is abundant vacant space in MTA stations, much of it commercial, that DCS will use to provide medical services to homeless New Yorkers as well as connections to longer term support. By providing access to a safe and reliable location to receive support, we limit incidents of mental distress. Its total cost is $10M.

Here, I will just say: this is a bad idea, a comically bad idea, and most New Yorkers can understand why immediately. The subway should be for one thing, and one thing only: helping people get where they need to go in a clean, orderly, safe way. Commercial sales of regular goods commuters need can fit into that picture (if they, like bathrooms, can be brought back to subway stations).

It is a hallmark of blue tape and everything bagelism to try to take something like the subway, built for one purpose, and try to make it fulfill a wildly different purpose, compromising both goals in the process.

Mamdani’s proposal would anchor a population in the subway that disrupts its primary objective in every way. This is not kind to them, and it is not kind to the subway or its riders.

Mark Levine, who I will be voting for for comptroller, has a serious set of proposals to address the mental health crisis. At the root of them is funding more long-term institutional beds for people who simply cannot live independently.

Final summary notes on Mamdani

For almost all of his policies, my analysis is similar in form and content to what I have written above. Free buses? No cost childcare? These all sound great on paper, backed by good intention. But they present terrible budget trade-offs when you get into the spreadsheet of it all, and his plan to pay for everything by “taxing the rich” is immensely myopic if your goal is to retain these people in the tax base; and he should really wonder—why does NYC get the policy results it does with an annual budget of $115 billion, and the highest per-pupil spending of any public school? Clearly, sheer money is not the problem. Just taxing more into that system ensures it will be ill-deployed as well, and earn voter retribution.

I simply do not think Mamdani would be a good mayor, that he fundamentally misunderstands the most vital components of our city, that he is deeply unserious with regard to public order, and so much more. Whatever good things he does propose are drowned by his core dedication to devastatingly bad ideas. I do not trust him to wield mayoral power.

And, at the end of the day, he is a socialist. He rejects the “market” prong of the market-government system that I believe we need to flourish. He would pull the Democratic Party into a less appealing direction, not just at the city level, but on the national stage. Along almost every axis, even those not discussed in this piece, I deeply reject him as a candidate. If you wonder, “But, Daniel, what about all the bad things Cuomo did?” my response is: he and Mamdani are not that different, but Mamdani is proposing a slate of things that are credibly worse.

Plenty of people have outlined Cuomo’s drawbacks at length, or even in entertaining videos. My goal here is to help give something resembling parity to Mamdani.

Lincoln’s exhortation

In 1838, a young Abraham Lincoln delivered what’s now known as his “Lyceum Address,” entitled The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions. He contends that our political institutions are fragile, a dear gift, and always primarily under assault from internal actors (rather than foreign adversaries).

To preserve those institutions, Lincoln has this to say:

[The memories of the American Revolution] were the pillars of the temple of liberty; and now, that they have crumbled away, that temple must fall, unless we, their descendants, supply their places with other pillars, hewn from the solid quarry of sober reason. Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defence. Let those materials be moulded into general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws

My recommendations in this piece are based on my best understanding of the facts. They have led me firmly in one direction. If you are not taken the same way, I still look forward to building a city with you, and working together to make New York greater still. I look forward to welcoming you to my events, and having you in my classes. I look forward to you being open about how you voted with me, trusting that you will be met with a firm handshake and a kind smile regardless.

But this is how I see things, with my application of reason as my guide.

Excelsior.

“In 1920, general uncertainty with regard to normal market levels caused a complete deadlock in building activity. The first and most important step in breaking the deadlock was to establish a degree of confidence in continuing high costs. Officials insisted that prices would never return to prewar levels. Even after a degree of confidence was effected, the unwillingness to invest and build remained.” How Tax Exemption Broke the Housing Deadlock in New York City: A Report of a Study of the Post World War I Housing Shortage and the Various Efforts to Overcome It, Citizens’ Housing and Planning Council of New York, Inc., 1960 (p.1-3).

Ranking a man who shut down Indian Point, transferred MTA funds to fund an upstate ski resort, prioritized glam projects over nuts and bolts fixes, interfered in NYCs COVID response because he didn’t like deblasio, harassed women is extremely disappointing. I can’t believe you’ve written in support of him

Personally, I don’t find opposition to Zohran to be a compelling reason to rank Cuomo at all. Cuomo is unacceptable as someone who has used tens of millions of NY taxpayer dollars covering his legal fees and will be easily blackmailed by the Trump admin (the DOJ is actively investigating him). We don’t need another Eric Adams. Cuomo is unfit for office.