NIMBYs and Bad Faith Procedure Almost Killed the New York City Subway

The past is not entirely different from the present // What we can learn from the first subways to build more of them today

On today’s episode of The Ezra Klein Show, entitled “In This House, We’re Angry When Government Fails,” Ezra makes the following observation:

The first contract to build the New York subways was awarded in 1900. Four years later — four years — the first 28 stations opened.

This same fact is noted on Patrick Collison’s “fast” page, which contains “Some examples of people quickly accomplishing ambitious things together.” The original New York City subway construction timeline is becoming a staple of the rising abundance movement—an example of how quickly we used to build great things, and a model for the future.

But building the subway was not easy, and it was constantly in danger of being killed. It was not as simple as “government decides to build the subway, awards the contract, and it is quickly executed,” a view which I think Ezra’s remarks might inadvertently propagate as they bounce around the internet (I don’t think this was his intention). It’s important to understand the harshly adversarial conditions under which the subway came to be, because they reveal how the subway really succeeded, and give us a potent example to which to appeal for modern legal change.

NIMBYs existed who wanted to block the subway. Private capital was scared to invest in it. State courts slowed it down, and pushed back the construction start date. The U.S. Supreme Court had to extinguish lawsuits seeking to stop construction. Politicians had to cut compromises left and right, including sub-optimally altering route plans, to account for the public fear of governmental corruption and construction-related disruption. Cultural commentators confidently opined that no one would want to spend that much time underground. Macro conditions repeatedly derailed the subway’s construction.

Sound familiar? Let’s take a closer look at a highly abridged list of obstacles that delayed the New York City subway. In the words of the New York City Chamber of Commerce, which wrote a history of how the first subway came to be:

The foregoing fails to convey even a faint conception of the discouraging delays that continually beset all efforts of the Rapid Transit Commission to accomplish the object [building a rapid transit network] for which it was created. No sooner was one obstacle surmounted than another, perhaps more formidable, was presented. This constant changing of the aspect of the question made necessary repeated revisions and alterations of the plans, all of which took time. Although there was an imperative demand for rapid transit by the people, who had by a large majority of their votes sanctioned municipal ownership, the city authorities and the courts were indisposed to promote the purpose.1

A basic timeline

If you want to get an idea of how much the subway was delayed, you need a basic timeline. While the history of the New York City subway arguably goes back to the 1860s, I will start in 1891—that is the year New York State passed the Rapid Transit Act of 1891, enabling New York City to create a subway,2 and the year after which London opened its first electric underground line.

The RTA of 1891 established a Rapid Transit Board that failed to find a company to construct the subway, and it was replaced by a new board established under the Rapid Transit Act of 1894. That board would not formally award the contract to begin construction until January 21, 1900—six years later. Even after the contract was awarded, the subway was beset with court challenges and other roadblocks, which its proponents admirably overcame to open it on budget and on time in 1904.

Court challenges against the subway

State and federal court challenges came in all varieties. For some relevant background: through the 1870s and 1880s, New York City and Brooklyn built out a vast network of elevated railroads. These were often killed, delayed, or bankrupted by private property lawsuits—businesses and individuals near the railroads claimed damages in the form of impeded light, air, and access to their property. These kinds of claims threatened the subway too, so they had to be extinguished by an 1895 amendment to the 1894 RTA.3

But even with those lawsuits calmed by the 1895 amendment, there were private property lawsuits, lawsuits arguing the rapid transit acts themselves unconstitutional, and opposition from the New York State judiciary itself. Some examples:

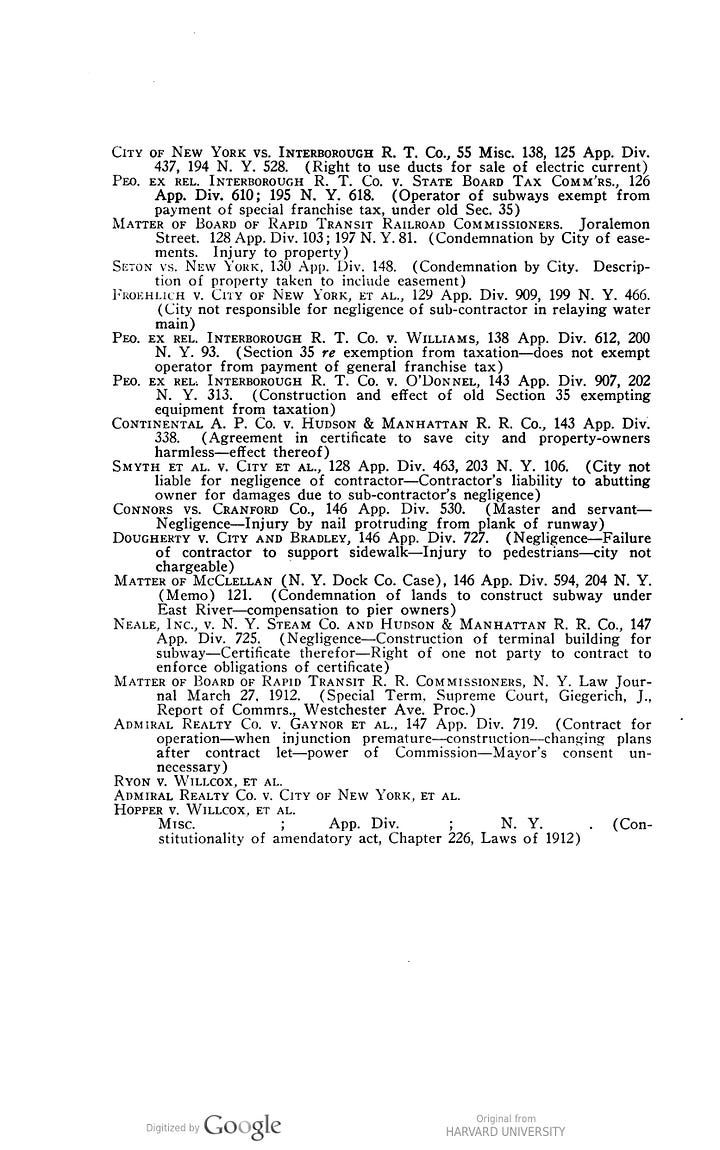

Underground Railway v. City, U.S. Supreme Court (1904): The plaintiffs (Underground Railroad of NYC and Rapid Transit Underground Railroad Company) sought to block the city from building the subway, claiming they had prior exclusive rights to build underground railways under the city streets. The Supreme Court disagreed, and allowed the subway to proceed—good thing too, because it was almost done when the Court ruled.

Barney v. City, U.S. Supreme Court (1904): a property owner, Charles Barney, sued to stop the construction of the subway tunnel under Park Avenue. Barney claimed the tunnel was being built 27 feet closer to his property than authorized by approved plans, violating his constitutional rights under the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court again disagreed, putting the matter to rest.4

In re Rapid Transit Commissioners, New York Court of Appeals (1895): this one is a real doozy. Per the Rapid Transit Acts, the Rapid Transit Board had to get permission to run a subway line anywhere. They could accomplish this by getting the consent of a majority of property owners along the proposed route, or, failing that, could get permission from the General Term of the Supreme Court.5 The Board couldn’t get property owner consent at one point, so they went to the General Term. The General Term refused to hear the application, since, according to a new state constitution that went into partial effect in 1895, it was to be replaced with “the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court” on January 1, 1896. They said they had no jurisdiction, effectively pausing any new subway construction that couldn’t get property owner consent until at least 1896. New York State’s high court reversed this, and required them to proceed. Per the high court’s sensible opinion: “The [constitutional] provisions should receive a reasonable [interpretation] and one that may not work a public mischief. [An interpretation] which shuts the doors of a court to all applications of this nature for one year and closes all operations of street railroad building in the state for that time (where an application to the court is necessary), ought not to be adopted without a plain mandate to that effect from the Constitution itself. We think no such mandate can be found.” This particular court would continue to throw up procedural obstacles beyond this case that delayed the subway by years, largely because of the judge’s personal opposition to the subway project.

Macro factors

The Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 crashed markets, sent unemployment through the roof, and generally made private capital more nervous about investing in new things. That included the New York City subway. The Panic essentially killed the Rapid Transit Board that was established under the RTA of 1891, ensuring that they would receive no bids for the subway (although they did receive one very unserious bid of $1,000). The private railroads that existed at the time, mostly dominated by Jay Gould’s Manhattan Railway Company, did not extend any serious bids either.

New York State’s Constitution of 1894

New York adopted a new constitution in 1894, which began to go into effect in stages on January 1, 1895. One major change was in the state’s judiciary. The so-called “General Term” of the Supreme Court would be replaced by the “Appellate Division” of the Supreme Court, and that change went into effect on January 1, 1896. This change gave an opening to the General Term to delay approval of the subway map, as I discussed just above in the previous section.

Consolidation: when the five boroughs joined together in 1898

Prior to 1898, “New York City” referred to Manhattan and, eventually, The Bronx. Brooklyn was a separate city, and the areas we know as Queens and Staten Island were largely farmland. They were all fused into one metropolis on January 1, 1898. This had massive legal effects that were a challenge for the subway in the short term. The newly consolidated New York City assumed all the debt of its formerly separate cities, which brought it close to its constitutionally imposed debt limit. This meant that it couldn’t issue enough bonds to pay for the initial capital outlay of the subway. By the time the Rapid Transit Board was ready to issue the contract in the late 1890s, consolidation caused another wave of delays until the city’s debt fell relative to its debt limit.6 City officials arguably delayed the subway’s construction by at least a year by simply moving slowly in response to the debt adjustment.

Risk aversion and prejudices

Cultural status quo bias, refusal to update

Many people misunderstood the subway proposal—they thought it would be like the London underground at the time, especially the one built in 1863. These trains were powered by steam, were dirty, and were a generally unpleasant experience. No amount of effort from the rapid transit board could get some people to understand that the New York City subway would be powered by electricity, and would be the world standard when it was completed. Many also doubted that New Yorkers would tolerate spending so much time underground.7

Private capital was too nervous to invest in the subway until 1900, and equivocated before then

All throughout the 1890s, various rapid transit companies expressed interest in building a subway. Few of them were serious, and when the time came to actually submit bids, almost none did. Further: The Manhattan Railway Company, which had an effective monopoly on the elevated train lines running through NYC, continually dragged its feet, promising to submit a bid, and never doing so. The rapid transit board waited for them, delaying the subway project by years, until they finally shut them out of the process:

The Manhattan Company refused to accept any of the franchises. It was unwilling to undertake the work of extending its traffic facilities. Its last opportunity had come and gone. It was controlled apparently by a belief that no solution of rapid transit problems could be obtained without its co-operation…A procrastinating policy had been successful with former commissions, and why should it not be in this case?8

Eventually August Belmont supplied the capital to begin building the subway, after the contract had been awarded to John McDonald. At the opening of the subway, he said: “If any especial credit is due to my associates and myself, it is that the financial end committed to our care required the exercise of a kind of courage not frequently demanded for an investment. It was a new and untried venture.”9

The boroughs outside Manhattan and The Bronx pushed back on the subway

The original subway only ran through Manhattan and The Bronx. Why? Because the lines were planned, and state legislation authorized, the lines to run only through New York County. In most of the 1890s, that meant only those two areas. After consolidation in 1898, the subway was still only planned to serve those areas, and the other newly minted boroughs objected to such an expense that would not benefit them—but would wall off the city’s debt capacity to be used in their service:

Another result of the consolidation was a tendency to array the influence of Kings and Richmond counties, and a portion of Queens, against the plans. At that time it seemed that the endeavors of the Board would be defeated or at least doomed to indefinite postponement.10

Some differences with the modern day

You could imagine many of the hurdles discussed above happening today, but the legal context of the 1890s is quite different from today. The examples are endless, but some large ones:

Environmental review: New York State passed its State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR) in 1975. That not only introduced large procedural delays when building things subject to it, it opened projects up to a firehose of litigation. “You didn’t follow proper environmental review procedure!” is a common, bad-faith line of litigation that opponents of anything use to delay, delay, delay. A live example: the Elizabeth Street Garden saga in Manhattan.

The MTA, and all intervening subway history since the city took the subways over in 1940: the subways were first built by private companies that returned taxes, franchise fees, covered the city bonds issued to subsidize their capital costs, and more. This was all on top of returning a profit. But a lot has happened since then, and we have acquired a web of institutions that run and oversee the subway. These all have their own inertia and political battles.

Philosophy: the philosophy of New York City and State leaders is plainly just different from their past counterparts. Growth and economic development were praised more easily, and “business interests” comprised the bulk of the city’s elite—today there are many rival elites, and they have priorities other than getting infrastructure built or economic growth. But I think the Abundance movement, which Ezra Klein and others support, is changing that.

Supplemental bibliography for further reading:

Rapid Transit in New York City (1905), and my associated book notes

Morris, John E., Subway: The Curiosities, Secrets, and Unofficial History of the New York City Transit System (2020).

The Elevated Railroad Cases: Private Property and Mass Transit in Gilded Age New York in the NYU Annual Survey of American Law (April 2006).

You can find this excerpt on page 116 of Rapid Transit in New York City (1905), or in my book notes thereof.

“An Act to provide for rapid transit railways in cities of over one million inhabitants”

For a history of these lawsuits and evolving jurisprudence, see The Elevated Railroad Cases: Private Property and Mass Transit in Gilded Age New York in the NYU Annual Survey of American Law (April 2006).

Regarding the 1895 amendment, from Rapid Transit in New York City: “The amended statute was passed in 1895. It provided that the city should extinguish all easements of abutting property holders that might be affected by the construction of the road, thus guaranteeing the contractor against the class of litigation which had proved so serious to the elevated railroads, and authorized the city to expend the addition sum of $5,000,000 for that purpose.” (86-87)

To be fair to his suspicions, which probably still don’t warrant a cessation of construction: “A half-built subway tunnel caved in along Park Avenue (then Fourth Avenue) between 37th and 38th Streets in March 1902, undermining the front walls of a row of grand town houses.” (see page 19 of Subway: The Curiosities, Secrets, and Unofficial History of the New York City Transit System)

“Like many New Yorkers, [land speculator Charles T. Barney] was in favor of the subway so long as it wasn’t built right outside his front door. As it happened, Barney lived in a town house on Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue) along the path of the first line, and he sued the IRT, seeking a court order to stop the work, arguing that the digging came too close to the foundation of his home. A judge denied his request, but Barney was right. The front of his house was undermined when the ground subsided along the tunnel in 1903. By then he had resigned from the IRT board.” (Subway, 139)

The “Supreme Court” is not the highest court in New York State, but rather the third highest. Above that is the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, and above that is the highest court, the Court of Appeals.

The debt limit is determined by the total value of assessed property within the city. Thankfully the state reassessed the value of New York City’s property after consolidation, finding it had risen. See Chapter 11 of Rapid Transit in New York City (1905).

These were both relayed by the subway’s chief engineer, William Barclay Parsons, on the 25th anniversary of the subway opening. See New York Times from October 27, 1929.

See Chapter 11: The Commission of 1894, in Rapid Transit in New York City (1905).

For more color, see John Morris’ Subway: The Curiosities, Secrets, and Unofficial History of the New York City Transit System (2020): “The financiers behind the street railways and elevated line companies, which were threatened by a subway, didn’t give up without a fight, however. They delayed matters by making vague offers to extend their lines, forcing the Board to postpone a final decision about the subway route. The ‘fine, high-minded, soft-hearted old gentlemen’ on the Board were no match for ‘the impossibly alert young fellows of Wall Street, with their unlimited money, with their control of the political machines, with the best legal brains at their disposal,’ journalist Ray Stannard Baker write in 1905, explaining the years of delay.” (p.11)

Rapid Transit in New York City, p. 172

Rapid Transit in New York City, p. 100

There is a lesson here that applies to housing construction as well: streamlining the permitting process is well and good, but if the developer can't get financing on terms that make the project pencil out, it won't matter.