1898: The Birth of New York City

A short review of the consolidation of New York City and the birth of the boroughs, one of the most consequential political events in American history.

See this essay’s companion piece: “1989: New York City’s New Government and the Fall of the Board of Estimate”

When people think of New York City, they think of the five-borough Colossus: Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island. But NYC wasn’t always arranged this way—in fact, the municipality’s modern political configuration was highly contingent, not guaranteed, and not universally wanted.

Prior to January 1, 1898, there were no boroughs. There was no Colossus. There was a profusion of different cities, towns, and counties clustered around New York Harbor. And this collection was threatened, not at all secure as the “capital of the world.”

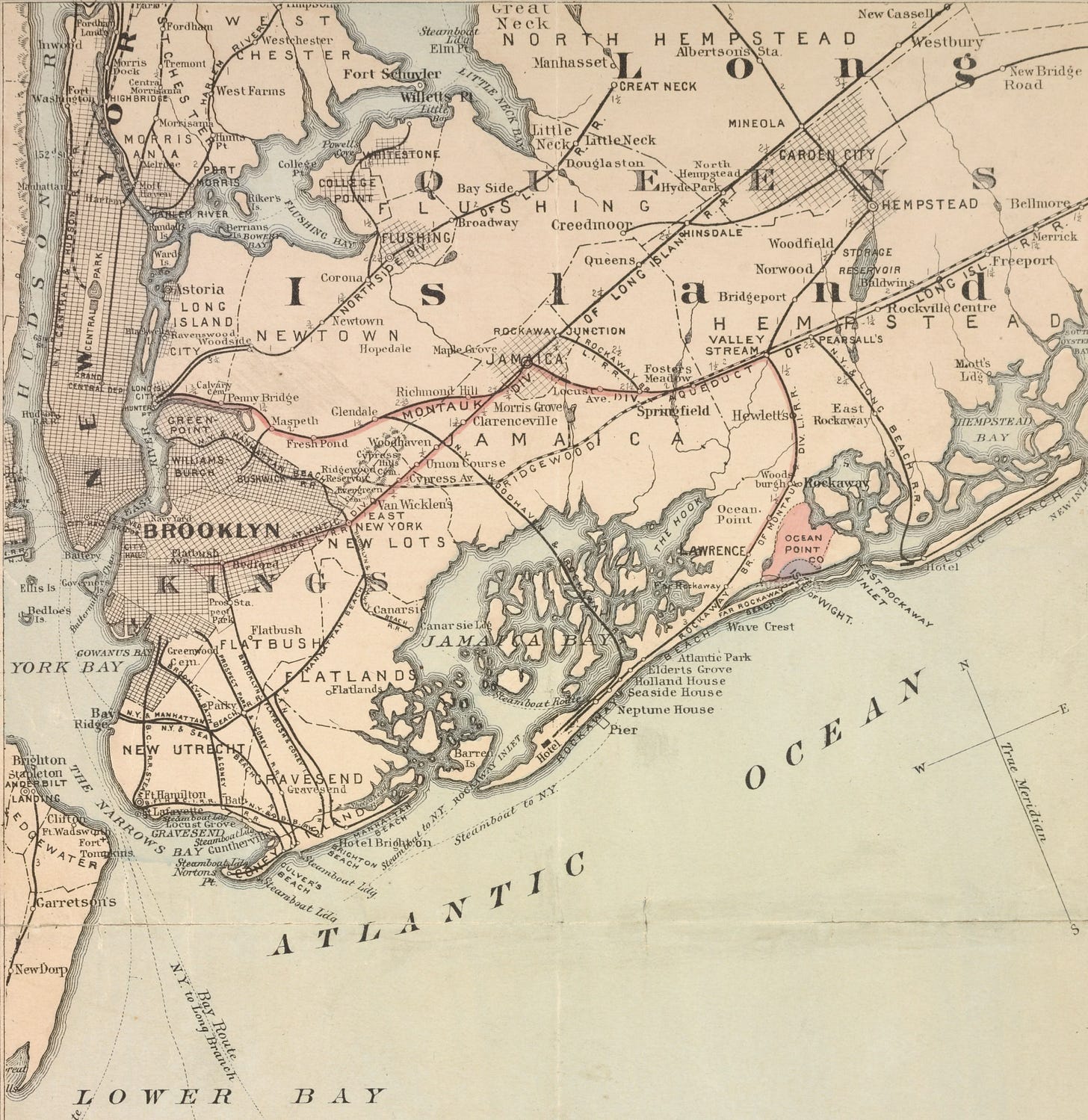

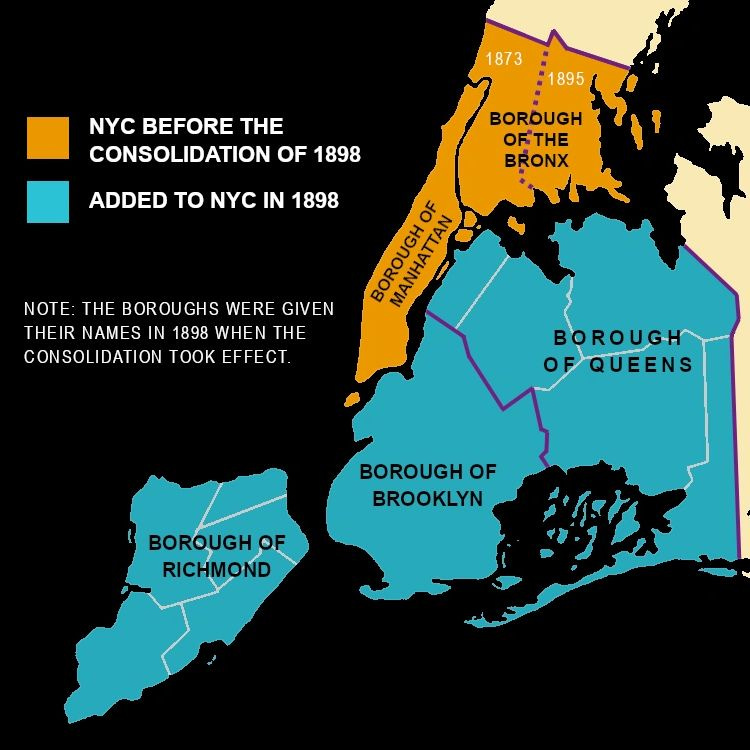

As of 1897, “New York City” referred only to Manhattan and the Bronx, which were united in New York County.1 Brooklyn was a separate city. Queens County, which took up modern day Queens and Nassau counties, was a largely agrarian collection of small towns. And the towns of Richmond County had not yet become the Borough of Richmond, which would be legally renamed Staten Island in 1975.2

This is how, and why, they came together, creating the five boroughs and the united Greater New York that we know today.

This is the story of the act known as “the consolidation.”

The nineteenth century: toward consolidation

Although consolidation had been discussed for decades, both New York City and Brooklyn were actively growing via the same tool right up until they were merged with each other.

New York annexed the western half of the modern day Bronx in 1873 (effective 1874), and the eastern half (east of the Bronx River) in 1895. In this way, the Bronx is “the first borough,” since it was part of New York City and New York County before the consolidation.

And throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, Brooklyn continued to swallow up the towns of Kings County until the two were finally coterminous in 1896. “Gaining control over Gravesend’s Coney was of particular concern, said the [Brooklyn Daily Eagle], for ‘the rescue of the island from barbarism, brigandage and bestiality requires that it be made part of the limits and jurisdiction of Brooklyn.’”3

Why consolidate further?

Many of the arguments for consolidation were straightforward: if you have a large area under the same political administration, you can introduce economies of scale through that administration, eliminate deleterious competition among its smaller units, and manage common resources far more effectively.4 A modern urbanist/economist might also note that knocking down barriers between otherwise separate municipalities could foster even more greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts urban agglomeration effects.

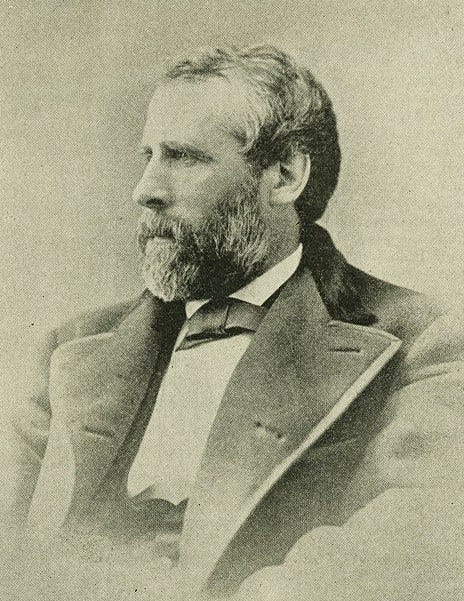

These were, generally, the reasons that proponents of consolidation gave throughout the nineteenth century, especially the architect of the consolidation—and Father of Greater New York—Andrew Haswell Green.5

There is thus, in the world over, no other area of a hundred and fifty square miles whose welfare could be better promoted by one general administration; yet there is not, in the world over, another like area so disturbed by multiplicity of conflicting authorities…It is divided up and parcelled out among two States, four cities, and six counties. I trust I may be excused for saying that the arrangement is a travesty upon government.6

The situation at the mouth of the Hudson before 1898 would be familiar to the residents of, say, Los Angeles today. LA is cut into a horrendous amount of smaller municipalities, each with their own separate books of law, zoning codes, jurisdictions, and more. Even though these are all functionally the same urban area, it is difficult (verging on undoable) to plan for the whole region in any consequential way.

Many individuals and institutions agitated for consolidation, and some of the most forceful arguments for it came (unsurprisingly) from Andrew Haswell Green, who was the president of The Commission of Municipal Consolidation Inquiry that the New York State government convened in 1890.7

A non-comprehensive list of contemporary arguments in favor of consolidation:

New York would fall as the de facto capital of America, and become the second city to a quickly growing Chicago. “European banking and export firms might shift their American branches to the heartland; corporate headquarters would soon follow, taking professional firms along; the market prices of stocks and commodities would get set in the interior; manufacturing would steal away; New York’s property values would scud downward. Doomsayers recalled how the power and prestige of Philadelphia, once America’s chief city, had slowly bled away once it was surpassed numerically by its Hudson River rival.”8

A New York Times headline from November 4, 1894 The localities around New York Harbor were already one urban area, and were already consolidating in effect, if not in fact. Andrew Haswell Green called it “[a] sham arrangement of separate municipalities.” The region had a unified job market, with people flooding into Manhattan (then “New York City”) to work from surrounding municipalities like Brooklyn or Long Island City.9 The only problems they faced were disjointed infrastructure and law resultant from “a commonwealth of divided municipalities.”10 For example…

Infrastructure, like transit, could be coordinated on a more regional basis. The Brooklyn Bridge, completed in 1883, is an example of New York and Brooklyn consolidating in effect, but since they did not consolidate in fact, you had terrible situations like this: “The Brooklyn Bridge, linchpin of the new prosperity, was a casualty of its own wild success…Brooklyn and Williamsburg merchants clamored for additional East River bridges, but New York’s commercial and political establishment were hostile; [New York] Mayor Grant, not atypically, worried in 1889 that the benefits of new construction would accrue wholly to Brooklynites. The bridge was symbolic of other irrationalities. There was no through transport across it. Manhattan transit cars traversed the bridge, dumped their passengers, turned around, and returned to Manhattan; and vice versa for Brooklyn trolleys.”11

Brooklyn was running out of water and had no way to get what it would need to keep growing, and New York had plenty to spare. “Even the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, one of the staunchest Brooklyn independista organs, came out for a merger of the two cities’ water supplies, though nothing else.”12

Brooklyn was running out of borrowing power to finance further expansion! The state constitution prevented cities from issuing debt greater than 10% of their assessed property value, and Brooklyn’s tax base was far narrower and more residential than New York’s. “In 1891 Brooklyn’s population was fully half that of New York’s, but it had only a fourth as much taxable property.”13

Consolidation was a way to unite the users of New York city services with the city’s taxpayers. Plenty of people came into the city to work and consume its services, but by living in a separate municipal jurisdiction, they avoided paying taxes to support those things. Consolidation prospectively united the municipality with all of its effective citizens and their tax payments.14

Protecting the commons: Pollution, health, and crime all crossed municipal boundaries, and needed to be coordinated across them. “Upon these elements it is impossible to fasten municipal jurisdictions. We cannot parcel out the air among us nor partition the fleeting tides.” In fact, throughout the nineteenth century, New York and Brooklyn had at various points already joined their health, police, and fire administrations.15 Consolidation proponents also argued that docks and common waterways would be best managed under one government, and Andrew Haswell Green said lack of consolidation “…relegates their custody to the irresponsible charge of all, without permitting them to the special concern of any.”16 Classic governing-the-commons problem.

A larger city is a stronger city. A Greater New York could provide an effective counterbalance to the rise of the national corporation, particularly the railroads, who could otherwise lay their track wherever they pleased without regard for good planning or local impact. But beyond American corporate power, a divided New York City would not be able to martial self-defense against foreign attack: “Every power on the globe except our own is advised that defenceless upon the American coast there stands a group of our most opulent cities within gunshot from the open sea—at the one point along our entire coast where we are most open to assault, we have accumulated greatest temptations to invite it and smallest means to repel it.”17

The fight for consolidation

Despite the list above, there was strong resistance to the idea of uniting New York and Brooklyn especially. You could organize most of the resistance along the lines of taxes, political machines, and cultural character. Everyone thought that they were going to be overrun by, and have to pay for, everyone else. These kinds of arguments are similar to (and often the same as) arguments that came up in the mid-twentieth century, when formerly consolidated municipal areas began to fragment again as suburbs splintered away from their urban cores.18 They are, in fact, similar to arguments that New York City is having with its suburbs today (particularly those on Long Island) about housing policy.

Regarding taxes: Brooklynites feared that they might have to shoulder a larger tax burden to pay for the tenements, slums, and welfare programs of Manhattan.19

Regarding political machines: Some Brooklynites, coming from a Republican city, feared a takeover by Tammany (the Democrats) and drowning in “…a flow from Manhattan to Brooklyn of the ‘political sewage of Europe.’”20 And the Tammany political machine was nervous about being overwhelmed by trying to manage a much larger city. No power center was sure it could maintain its grip on an enlarge whole.

Regarding cultural character: New York was the large city of foreigners (Catholics!) and immigrants, of trust-dominated commerce and billionaires, of the arts and opulent culture. Some Brooklynites “…expressed a desire not to ‘vote away our [Protestant] religion’ and to remain a ‘a New England and American city.’”21

Of course, the reality of the situation was that New York, Brooklyn, and all the smaller municipalities around them were already united and mixed along cultural, commercial, and political lines. Republicans were in New York, Tammany in Brooklyn. Bridges and ferries removed rivers as barriers. The consolidation cake was, in an important way, already baked.

In a non-binding 1894 referendum on the question of consolidation, almost every polled municipality—including Brooklyn, by 277 votes—voted in favor of it.22 While this certainly added momentum to the movement, it wasn’t until May 11, 1896, that the New York state government passed the consolidation bill, overriding vetoes from both the mayors of New York and Brooklyn to do so. And it wasn’t until 1897 that the state government ratified the new city charter, boroughs and all, overriding yet another veto from New York’s mayor to do so.23

On May 5, 1897, the New York City that we know today was signed into law by Governor Frank Black.

And on January 1, 1898, it became the reality we’ve been living in ever since.

After consolidation

Since 1898, New York City’s government has changed a lot, including a wholesale revision (only rivaled by the consolidation) in 1989 when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the city’s central governing body, the Board of Estimate.24 In its place we got our modern, enlarged, powerful City Council; our sidelined borough presidents; and more.

We’ve even had a few secession attempts. Staten Island got the furthest, because they actually voted to leave in 1993, but their efforts died on state constitutional grounds.25

And different parts of Queens have contemplated leaving ever since consolidation happened.

The story of New York City’s consolidation is many things, but I think it’s important because it shows how malleable our governing structures can be—and how contingent their form is. The city government that we have today is quite young, with inherited pieces of the older system established in 1898. It’s in flux. We can shape it, just as others shaped it in the past.

And if you aren’t in NYC, realize: your city (state and country’s) history is probably stranger than the model you have in your head. There is possibility there for the future, and operational knowledge for the present.

Excelsior.

Principal sources and some further reading:

Wallace, Mike, Burrows, Edwin. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press, 1999.

Wallace, Mike. Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Green, Andrew Haswell. New York of the Future: Writings and Addresses by Andrew Haswell Green, 1893.

This podcast episode of The Bowery Boys, “The Birth of the Five Boroughs” (2022)

This podcast episode of The Bowery Boys, “Who was Andrew Haswell Green? Say hello to “the most important leader in Gotham’s long history.” (2019)

nyc125.org has a great timeline of consolidation

The western half of the Bronx was annexed to New York City in 1874 (although it was authorized by the state legislature in 1873) and the eastern half of the Bronx (the half east of the Bronx River) was annexed in 1895 (Greater Gotham, pp. 52-54).

Manhattan and the Bronx both existed within New York County until Bronx County was formed in 1912 (and went into effect in 1914; it was the 62nd, and final, county in New York State).

Yes, you read that right, Staten Island’s legal borough name wasn’t Staten Island until 1975. See: New York Times, “Staten Island Is Official, The Name Dutch Chose,” April 9, 1975.

Gotham, p. 1231.

A principal guiding idea behind consolidation was administrative efficiency. Under one government, a group of previously discrete municipalities would no longer compete with each other—similar to US states before the federal constitution went into effect in 1789. The first Constitutional Convention at Annapolis in 1786 (the mostly-failed one before its more famous sibling in Philadelphia less than a year later) was aimed at remedying trade wars and regulating commerce and law among the new states. Prior to the modern US federal government, states were united under the Articles of Confederation, which gave functionally no power to the national government of the United States, and left most things completely up to warring state governments.

New York of the Future, p. 12.

Chapter 311 of the Laws of 1890 put it like this: “An Act to create a commission to inquire into the expediency of consolidating the various municipalities in the State of New York occupying the several islands in the harbor of New York [Manhattan, Long, and Staten].” This particular act can be found in many places, but it’s also reproduced in New York of the Future, p. 33.

Gotham, p. 1223.

From The New York of the Future, p. 29:

It is not impossible that some competing intelligences demonstrating upon other lines, and some co-operative ignorance demonstrating upon our own, may in time bring about the result that New York shall be operated in the chief relation as a seaport and serve to some interior position the secondary use that Hamburg renders to Berlin, that Havre rends to Paris, Southampton to London…”

New Yorkers’ fear of an ascendant Chicago wasn’t helped when it won the 1893 World’s Fair:

“This fear took tangible form in 1890, when Congress gave the midwesterners the go-ahead…The idea of a World’s Fair had been broached back in 1882, and ever since the two colossi had been competing for it furiously. Defeat seemed another doleful indicator of metropolitan decline” (Gotham, 1223).

Some critics at the time argued that consolidation was just a vanity project—bigness for the sake of bigness. Andrew Haswell Green rejected that argument completely. He not only argued the importance of magnitude for national pride and commercial competition, but said: “Were this criticism just, our community is the only one in history which had heeded it to the point of dwarfing our real dimensions under the sham arrangement of separate municipalities” (New York of the Future, p. 56).

Also, regarding housing, people have always been commuting into Manhattan from their cheaper “outer borough” locations: “So strong, however, is the passion of our New York population to own a home that many, unable to acquire it here, purchase lots in suburban towns; others, for purposes of economy, find transient homes for their families upon the opposite side of our jurisdiction line. Others do the same for the reason that a domicile in Brooklyn or Long Island City or Staten Island is more convenient to their work in the metropolis than such a residence with the metropolitan boundaries as their means can afford would be” (New York of the Future, p. 51).

This phrase comes from an 1894 New York Times piece, “Vote for Greater New-York” (Oct 16, 1894) that extensively quoted Andrew Haswell Green prior to the November 1894 non-binding referendum on consolidation (that passed almost everywhere!).

Gotham, p. 1228

Gotham, p. 1229

Gotham, p. 1229

“…there are very many thousands of persons earning a livelihood here who vote elsewhere, and very many who vote here who have the tie of merely transient domicile and whose prospective homes are situate in other jurisdictions…as a result there is produced a character of citizen who is a drudge in his field of work and a dummy in his sphere of citizenship” (New York of the Future, p. 51).

“For fourteen years, from 1857 to 1871, New York, Brooklyn, and Staten Island were under a join police administration, and from the year 1856 to 1871 they constituted one Health and one Excise Department” (New York of the Future, p. 18).

These unified instruments of administration were ended by the Tweed Ring of Tammany Hall, with the so-called “Tweed Charter” that transferred many of these administrative powers from New York State to New York City (Manhattan) directly.

On the Tweed Charter of 1870, from Gibson’s Legal Research Guide (4th Ed), p. 442 (emphasis added):

In 1870, William Marcy “Boss” Tweed took advantage of Democratic control of the legislature to successfully engineer the passage of a new charter. Reported to have cost Tweed millions in bribes, it was designed to restore city control over its own government. The state commissions controlling parks, police, and public health were eliminated and the New York County Board of Supervisors was abolished. In a move with major historical implications, a Board of Apportionment was established with the power to estimate and apportion funds for each department of the city government. Its members were the mayor, comptroller, commissioner of public works, and the president of the parks department.

The office of the mayor was strengthened by being given the power to appoint the heads of ten new executive departments. It now took a three-fourths vote by the council to override a mayoral veto. The Charter of 1870 and its 1871 amendments also provided for a Board of Aldermen consisting of fifteen members elected at large, with assistant aldermen elected from each assembly district.

New York of the Future, p. 14.

New York of the Future, p. 42, regarding foreign attack.

Regarding the municipal power as a counterbalance to corporate power, you can see p. 16: “…all private interests tend to consolidation and trusts. The only interest which refrains is that of our unselfish, thoughtless peoples and their fatuous municipalities, which in broken form carry on desultory and futile war against the organized forces of relentless and absentee capitalism…The corporate powers here represent the regular force, and our divided municipalities, though invested with responsibility of protecting all that belongs to the people in the sphere of civil administration, represent the guerillas. The continuance of this relation between the corporate power and the power of the people depends upon the length of the period during which we shall choose to maintain the attitude of municipal disseveration and refuse to assume that supreme mastery of the situation which union of our people alone can secure.”

In my college senior thesis, which was on secession, I discussed municipal annexation and secession in the context of Pawnee and Eagleton, Indiana, from NBC’s Parks and Recreation. Neither my thesis advisor nor my informal faculty advisors wanted me to put that in the thesis, but I did anyway and got marked down for it. No regrets, baby!

The pro-consolidation Brooklyn Consolidation League (BCL) said “…there was no escaping such ills in any event. A man might ‘withhold charity, but he cannot dodge taxes swelled by crime and pauperism,’ and every breeze was freighted with tenement-spawned germs” (Gotham, p. 1230). Basically: Brooklyn either needed to help pay for the poor, or pay for increased taxes to manage the effects of not caring for them in the first place.

Gotham, p. 1233.

Gotham, p. 1233.

“Ironically, it was the newly conquered colonies of Gravesend and New Utrecht that, in voting heavily for consolidation, overcame the negative majority in Brooklyn’s imperial center” (Gotham, p. 1232). Brooklyn annexed smaller towns, and then the voters of those small towns helped push Brooklyn into union with New York.

Gotham, pp. 1234-5.

This article, which I excerpt below, provides a good timeline of the Staten Island secession attempt, largely driven by the demise of the Board of Estimate, which gave Staten Island disproportionate representation in city affairs. But rumblings began as early as 1900!

[In 1989], the state Legislature passed a measure signed by then Gov. Mario Cuomo authorizing a study and initiating the process for Staten Island to secede from New York City on the last day of its legislative session.

By 1990, Staten Islanders voted overwhelmingly in favor — 83 percent — of a secession study and by 1991, Cuomo swore in a New York State Charter Commission for Staten Island.

Two years later, in 1993, Staten Islanders approved — 65 percent — a non-binding referendum to secede from New York City and the state Senate also approved a secession bill.

But those efforts came to a halt when former Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver refused to allow a similar measure to be voted on in the Assembly without a “home rule message” from New York City.

The city never held a secession vote and the measure for Staten Island to secede died in committee.

Thanks! I didn’t know about AH Green or that Staten Island used to be called Richmond before reading this 💡