New York's Great Uncelebrated Friendship: Theodore Roosevelt and Jacob Riis

One of New York City’s great civic stories is the friendship between Theodore Roosevelt and Jacob Riis. Their friendship would not only shape New York City, but the nation.

They showed that New York needs both natives and newcomers, the wealthy and the scrappy, and a union of those willing to take action.

Who were Theodore Roosevelt and Jacob Riis?

The question might seem silly to those who know both men, but most people don’t.

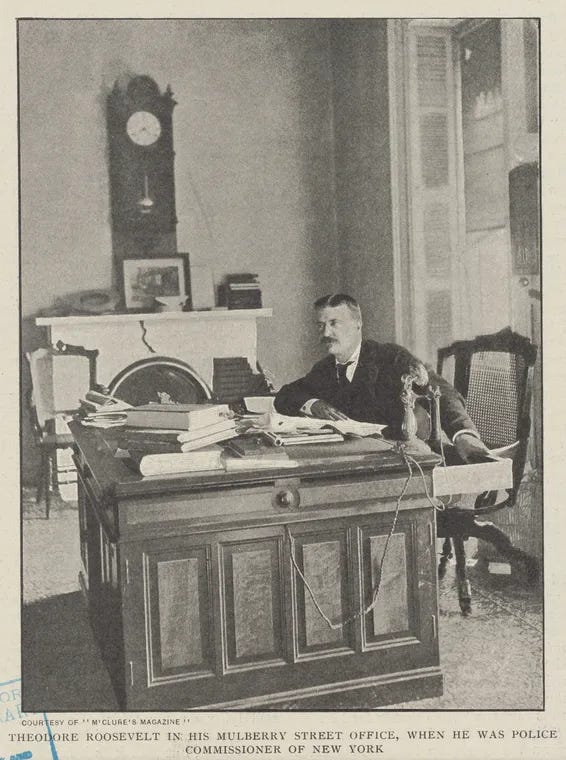

Theodore Roosevelt was a native New Yorker born into generational wealth just before the Civil War. Besides being a prolific writer, he served in the New York State legislature, the federal Civil Service Commission, as president of New York City’s police commission (1895-1897), as undersecretary of the navy, as governor of New York, and—what most people know—as president of the United States.

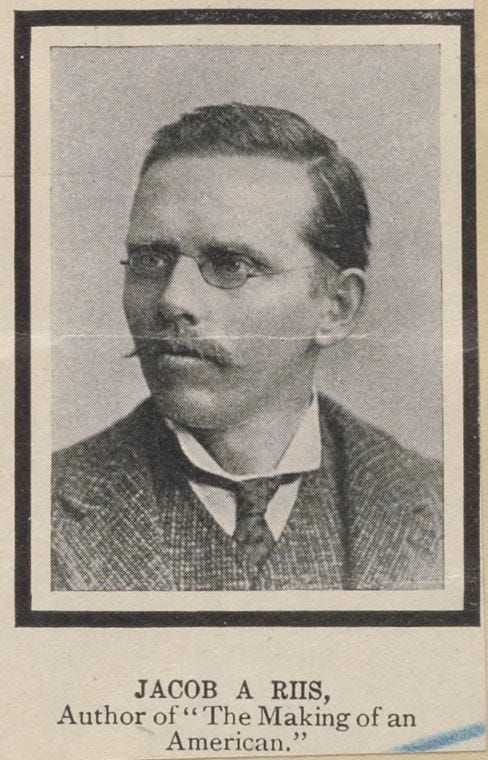

Jacob Riis was a poor Danish immigrant to New York and the United States whose first major work was How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York (1890). He was a carpenter, a writer, a photographer, a photojournalist, and a social activist on behalf of New York’s poor.

Although the circumstances of their birth and many superficial elements of their lives were counterposed, Roosevelt and Riis shared a deep commitment to similar values: fairness, care for the poor, good government, helping children and young men, and fighting political corruption.

The friendship begins with Riis’s book, the partnership with Roosevelt’s role as head of the NYPD

Their friendship was forged when Roosevelt read How the Other Half Lives after it came out in 1890. In his autobiography, in the sixth chapter on his time with the police department, he writes:

The man who was closest to me throughout my two years in the Police Department was Jacob Riis. By this time, as I have said, I was getting our social, industrial, and political needs into pretty fair perspective. I was still ignorant of the extent to which big men of great wealth played a mischievous part in our industrial and social life, but I was well awake to the need of making ours in good faith both an economic and an industrial as well as a political democracy. I already knew Jake Riis, because his book "How the Other Half Lives" had been to me both an enlightenment and an inspiration for which I felt I could never be too grateful. Soon after it was written I had called at his office to tell him how deeply impressed I was by the book, and that I wished to help him in any practical way to try to make things a little better.

As President of the Police Board I was also a member of the Health Board. In both positions I felt that with Jacob Riis's guidance I would be able to put a goodly number of his principles into actual effect. He and I looked at life and its problems from substantially the same standpoint. Our ideals and principles and purposes, and our beliefs as to the methods necessary to realize them, were alike.

Their deep friendship and professional collaboration would last for the rest of their lives, running through every level of government and across social and policy issues, until Riis died in 1914. That year, Roosevelt wrote a short obituary of Riis in The Outlook that would be included as the introduction to subsequent editions of Riis’s autobiography, The Making of an American (1901):

It is difficult for me to write of Jacob Riis only from the public standpoint. He was one of my truest and closest friends. I have ever prized the fact that once, in speaking of me, he said, “Since I met him he has been my brother.” I have not only admired and respected him beyond measure, but I have loved him dearly, and I mourn him as if he were one of my own family.

But this has little to do with what I wish to say. Jacob Riis was one of those men who by his writings contributed most to raising the standard of unselfishness, of disinterestedness, of sane and kindly good citizenship, in this country. But in addition to this he was one of the few great writers for clean and decent living and for upright conduct who was also a great doer. He never wrote sentences which he did not in good faith try to act whenever he could find the opportunity for action. He was emphatically a “doer of the word,” and not either a mere hearer or a mere preacher. Moreover, he was one of those good men whose goodness was free from the least taint of priggishness or self-righteousness. He had a white soul; but he had the keenest sympathy for his brethren who stumbled and fell. He had the most flaming intensity of passion for righteousness, but he also had kindliness and a most humorously human way of looking at life and a sense of companionship with his fellows. He did not come to this country until he was almost a young man; but if I were asked to name a fellow-man who came nearest to being the ideal American citizen, I should name Jacob Riis.

The lessons of Roosevelt and Riis

1) New York needs natives and newcomers

New York’s cultural discourse has regular flare-ups of “anti-transplant” sentiment. But those who divide natives and newcomers have an incorrect, impoverished view of their own city, not to mention an off-putting dislike of their fellow Americans and strivers from around the world.1 The real divide is between those who have married New York, and those who have not.

Roosevelt and Riis both understood this, as have all great New Yorkers who’ve endeavored to make this, our home, a better place:

Riis became TR’s most important ally in doing police work, and he changed forever the way Roosevelt saw his home town.

Riis could show the new commissioner the city as no one else could, and he meant to show him more than crime. He recalled that TR wanted to learn everything about how the city lived at night, its sights and sounds as well as its human landscapes. The irony of a recent immigrant showing a native New Yorker the city where he was born reminded both of them that the Knickerbocker in evening clothes and pink shirts knew the club world of the Union League better than he knew the piers in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge or the shops of Delancey Street.

…With Riis as his right-hand man Roosevelt learned the names and faces of the immigrant families who sewed shirts at home or peddled rags or fruit on the street.2

Further: Maximum New York and its classes were created by someone who adopted New York as his home, but who grew up on a farm in Indiana.

2) New York needs partnerships between the wealthy and the scrappy

Grave perils are yet to be encountered in the stormy course of the Republic—perils from political corruption, perils from individual laziness, indolence and timidity, perils springing from the greed of the unscrupulous rich, and from the anarchic violence of the thriftless and turbulent poor.

Theodore Roosevelt delivered these remarks in the conclusion of his 1893 speech “The Duties of American Citizenship,” and he points to something important. It does not matter what your level of wealth or station in life are—you can be bad. As he and Riis demonstrated, you can also be good.

Just like New York needs an alliance of natives and newcomers to thrive, so it needs an alliance of wealth and power with scrappy creatives. Both bring something indispensable to the civic table, neither is exclusively the “real” New York, and they are best in partnership.

Roosevelt could not have shaped his police work as effectively without the scrappy, creative work of Riis. Riis could not have converted his hard-won insights into sweeping policy reform with Roosevelt. One simply needs both.

Any political project that tries to pit these two groups together will wind up making them both worse off, although a political entrepreneur could siphon off a social and monetary profit from this social destruction (many do, many try). The far better, positive-sum enterprise is productive partnership, with each recognizing the necessity of the other.

3) New York needs people willing to take massive action together

Both Roosevelt and Riis overflowed with energy, zeal, and purpose. They frequently outran and outcompeted their contemporaries, and found, in each other, an atypical willingness to do. To take action.

While their penchant for massive action was undeniable, no incident is a better illustration than their donning of hoods, sneaking around New York City at night, and catching police officers in dereliction of their duty:

While Roosevelt investigated as many of these claims as he could, he also deployed far more of his time than his predecessors to simply watch his officers do their jobs. He did far more work, and took massive action. This approach transformed the police department:

“[Roosevelt] delighted in making surreptitious nocturnal tours of the city, accompanied only by his friend (and publicist) Jacob Riis (whom Roosevelt had sought out after reading his Other Half). Dressed in black cloaks and wide-brimmed hats, the duo crept up on errant bluecoats sneaking beers in saloons, nabbing them while their mustaches were still drenched with incriminating foam.”

“On one early morning patrol Riis took TR along First, Second, and Third Avenues, where they found one policeman asleep on a butter barrel and quite a few absent from their beats. Commissioner Roosevelt, with reporter Richard Harding Davis and Riis in tow, discovered a patrolman evading his duty seated in an oyster bar…The next day Roosevelt demoted the oyster bar dawdler, and word spread fast through the police force that the commissioner knew how to find loafers.”

Roosevelt created a credible threat of punishment for police officers who weren’t doing their duty, and that threat was often him personally catching them. This approach earned fear from slackers, and praise from the great mass of officers doing their job.3

Take inspiration from Roosevelt and Riis

New York needs more friendships like the one shared by Roosevelt and Riis. They were two seemingly opposite men, who nonetheless shared a common value system that allowed them to achieve more than either could alone. They were not divided by creed, place of birth, socioeconomic status, or any of the other social joints it is most un-American to attempt to carve.

Maximum New York (and me, Daniel) share their uniting value of taking action. And so: I am co-founding The Roosevelt-Riis Association with Maximum New York alumnus and esteemed citizen of New York Tom Laurino-Hanson.

The mission statement:

Inspired by the friendly partnership between Theodore Roosevelt and Jacob Riis, the Roosevelt-Riis Association works to cultivate active citizenship in New York City. The Association activates and organizes New Yorkers who love our city and wish to contribute to making it bigger and better. We enable talented New Yorkers to carry out the duties of citizenship effectively and joyfully, in pursuit of growth, efficiency, and order for New York City.

The formal launch announcement is coming soon. You can subscribe here to get it.

And if you think this is just another non-profit, you’ve got another thing coming.

Some supplemental reading:

Riis, Jacob, The Making of an American (1901).

Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, Chapter VI: “The New York Police,” (1913).

Dalton, Kathleen. Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life (2004).

H. Paul Jeffers. Commissioner Roosevelt: The Story of Theodore Roosevelt and the New York City Police, 1895-1897 (1994).

“How Theodore Roosevelt Reformed the NYPD,” Maximum New York (April 2025).

Immigrants from other countries are often not subject to the prejudice and xenophobia that others reserve exclusively for other Americans.

Dalton, Kathleen. Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life (2004), p.150.

“How Theodore Roosevelt Reformed the NYPD,” Maximum New York, (April 2025).

Instant subscribe - can’t wait to hear more!

Civic excellence with your pals is undefeated. Very cool to hear their story and excited for this initiative!