You Don't Have to Feel Bad About Politics

What's the political equivalent of asking someone if they've drunk any water today

If you equate “doing politics” or “knowing about government” with “having a bad time,” this essay is for you.

There are many reasons why you might feel this way, and most of them are not “the world is as bad as, or worse than, you think it is.”

Often people will feel physically bad, mad, sad, or whatever, but then they realize they haven’t:

Gone outside in a while

Drunk any water for 24 hours

Seen any people or friends for too long

Been physically active

Eaten anything besides nicotine mints and coffee

At which point they can course correct, go for a walk, eat a nice sandwich, and go to a movie with a friend.

The same kind of process plays out with politics. So let’s look at the political equivalents to going a day without water, or only shotgunning Cheetos for the past week.

You Haven’t Consumed High Quality Information, and Don’t Know Anything Real

Government and politics are sophisticated subjects, and getting a good grip on them, just like any subject, requires effort and error correction. Crucially, you need good, nourishing informational inputs, just like building a healthy body requires good food.

So what have you been eating, and for how long?

When I talk to people about politics, the most common, root cause of pessimism and anger is that they don’t know anything works; but they have made up a simplistic, incorrect version of the political system in their head that is broken. This model is fueled by a terrible informational diet.

Their emotions are real—they’re responding to a model of the world. It’s just that it’s a fake, untethered model.

Because of this, learning well about government (an uncommon experience) tends to make people more optimistic. Since their baseline expectations are essentially on the floor, there’s nowhere to go but up. As it turns out, many things work well, are going well, and are widely accessible.

But even when things are going poorly, properly understanding why is far better than having a fake reason. If you understand the mechanics behind a poorly functioning piece of government, you tend to feel more like you can do something about it. You feel a sense of agency, and you can see solutions and pursue novel affordances.

Knowledge (a healthy informational diet), coupled with the courage to act, dispels feelings of helplessness and impotent rage.

However: you don’t have to know everything about government to have a healthy informational posture toward it. The field is too vast for anyone to know everything. You will have things you don’t know about; in those cases, the healthy thing to do is select great informational proxies (most Instagram activists might be effective at certain things, but they don’t tend to spread great information—don’t just reach for what’s easiest).

Related essays:

You Have Made “Knowing About Politics” Part of Your Core Identity

Which means conflicting, but correct, information will feel like a terrible attack, because it will be challenging your core identity.

If you do this, there is a good chance you’ll wall yourself off from understanding a lot of things forever. The cognitive dissonance will be terrible.

And this is coming from a man who founded a civics school.

Keep your identity small. Reorient your approach to politics as someone who asks questions, doesn’t rush to judgment, and is often skeptical of those they’d otherwise be expected to agree with.

You Are Indigent and Can’t Afford Anything—With Political Capital

If you want to start a new business, you need to get some money—save it, get investors, or get a loan. You can’t just tell people that you want to start a business and have it magically appear, fully formed. You certainly can’t demand that a stranger set up your business for you, for free.

Nonetheless, most people approach politics with a mindset almost exactly like this: they make demands and declarations to people at parties about preferred policies, and maybe they write an email to an official demanding their preferred policy. They want the political system to give them what they want, and they offer it nothing in return, not even a basic attempt to understand the system.

In some respects I understand the impulse to demand something for nothing in politics—it’s the model most people have absorbed through culture and fleeting acquaintances with activist organizations: the politics of complaint. This approach, when anthropomorphized, is a random person shouting “I pay your salary!” at a government employee. But, as most have experienced, this approach is often as unsatisfactory as it is a waste of time. —How To Do Politics: The Political Capital Savings Plan

Work to earn political capital, which is generally done via pro-social activity. This will give you the means to do what you want.

Understanding how and whether political capital accretes also helps you adjust your expectations. You won’t try to buy something you can’t afford, and then be frustrated when your purchase is declined. You can realize that some things are so expensive that you’ll never be able to afford them, or at least not for a while. But maybe you’ll find out that you have more political capital than you thought!

Related post:

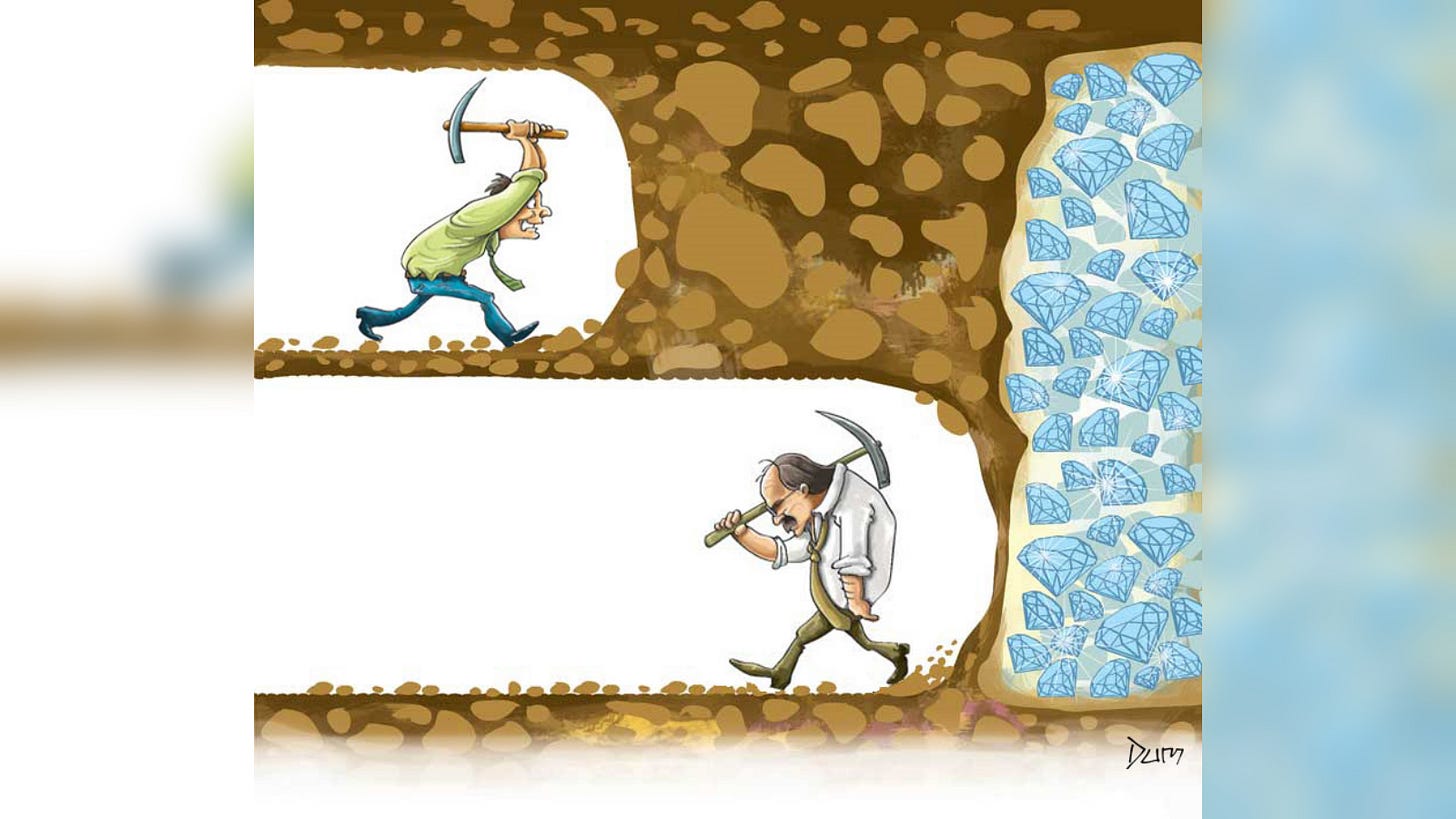

Your Time Horizons Are All “ASAP”

How long does it take for certain things to happen in government and politics? That’s a complicated question with a sprawling answer.

If you have no idea at all, you’ll tend to feel bad. Most people default to “shouldn’t this happen ASAP?” And, because they don’t have reasonable timelines, they also give up too soon, and so never get results.

You see this all the time with exercise and fitness. You won’t get strong after one workout—it just doesn’t work that way. But it’s very much within your abilities to get strong! And having proper time horizons helps you feel motivated.

Once you learn about government, you’ll start to understand the speed with which things move:

Fast (bad): if you could change fundamental law or the shape of government as quickly as a company could theoretically change its internal structures, you would have rule of man, not law. Law needs to be stable for many reasons; people need to know what to expect, they need to be able to make and keep contracts, etc. It is the stability of government and law that enables markets and other more dynamic elements to be beneficially dynamic in the first place.

Slow (bad): if you couldn’t change the law or shape of government hardly at all, you’d have the complete lack of adaptability characterized by (for example) procedural obsession over results. This is stultifying, and it pulls the dynamism of the other realms of human action down with it, or pushes them into black markets and less-than-ideal workarounds.

Fast (good): permitting of all kinds should be relatively automatic, not discretionary. It should be incredibly fast.

Slow (good): changing the fundamental nature of the government shouldn’t be easy to do, nor should it be impossible. But it should be far away from the easy end. —The Proper Speed of Government Is Often Slower Than You Want

Related post:

You conflate taking things seriously, and understanding them, with being mad or upset

I have a generally sunny disposition, and I’m a warranted optimist with regard to New York City and American politics.

Two common, bad responses to this are:

“Well, the only reason why you can think things are going well is because you’re too privileged to have experienced anything bad.”

“If you aren't angry, you aren't paying attention.”

I reject both of these sentiments when they’re expressed toward me, or anyone.

At their core, they contend that knowledge of reality means feeling angry and pessimistic. So being knowledgable almost certainly means you are condemned to mental illness.

This is epistemic arson. It is emotional blackmail. And it ignores the plain fact that the human response to challenging circumstances is more complex than that. We are resilient creatures capable of humor, camaraderie, and even everyday happiness in the midst of horror. In fact, it is good that this is true!

Do not go out of your way to find immiseration, or force it on others. Not only is it wrong, but on a tactical level it burns everyone out.

Reality is what it is, and that might wind up being good—if you’re in America or New York, it often means that.

Your Actions Are Mismatched To Your Desired Outcomes: The Trap of Voting and Protests

This is related to having proper time horizons and learning to earn political capital.

Doing things in life requires sufficient means for your ends. Simple enough idea—that is often forgotten in politics.

A common manifestation of this amnesia is when people automatically expect voting and protesting to do anything, especially in the absence of doing anything else.

Culturally these two feel like they should solve something, but often they don’t, and they can’t.

As tools they have some advantages: you don’t have to know anything to do them! You can just show up and take someone else’s (literal) marching orders, and plenty of people do that. But if you, personally, don’t know how your action will connect to larger achievements, it’s easy to feel burned out and jaded.

You need to learn what means are connected to your desired ends.

Voting is often insufficient:

Many races are severely uncompetitive or have no challenger, and elected officials in NYC will even brag about achieving North Korean levels of vote share in a race where they were the only person on the ballot. Voting is not a meaningful part of the political system in many places—the effective winner of the election was selected before it began.

By imagining you could not vote, you will realize that you might actually be in the same scenario as if you could vote—in either case, you have no impact on an electoral outcome. But you cannot stop the line of thinking there, unless you want to be mired in nihilism and inaction, using the badness of others as an excuse to avoid cultivating agency yourself. There is actually plenty you can do, and you can have a good time doing it. But it requires more than voting.3

And even if you live in a place with competitive ballots, all of this still applies. Imagining away your right to vote allows you to focus on what happens prior to the vote, and seeing what you can do there. Your action could be useful whether or not your final ballot is competitive.

So now you must ask: what is the process (or processes) that selected that person for the uncompetitive ballot? Are those fair (they might be)? Who is involved? How might you get involved in those processes, and exert genuine effect on who gets on the ballot? This is just as important to a healthy democracy as voting. Finding out the answers to these questions will be overwhelming at first, but I will help, and so will other Maximum New Yorkers. It’s not magic. It’s politics. —What if You Couldn’t Vote

And protests almost always need political actors on the inside of the establishment that’s being protested. Often those insiders will do work that goes vastly under-appreciated and unknown to protesters.

Related post:

You Don’t Have Good Politics Friends

A good politics friend is someone who is directly connected to the political realm. They have political capital, have friends who hold elected/appointed/hired positions in government, are a good knowledge proxy, and they have an even psychological keel.

If you hang around these kinds of people, or even just one, it’s easier for you to become like them. Get a good politics friend who raises your ambitions.

It’s like making a resolution to go to the gym. If it’s your first time trying to get strong, the gym will likely defeat you. It’s a lot of new stuff all at once: the machines, the social norms, the food/diet, all the conflicting information on the internet, etc.

But if you hang around with people who are good at getting strong, and you go to the gym with them, you’ll have a much better time. They help you, give you an immediate sense of community, and jazz you up.

I will be your good politics friend, or at least your good politics teacher so you can become a good politics friend to others.

You Have Bad Norms, and Are Rude

Norms are shared standards of social behavior. The norms can be legible and formal, in which case they’re set out in an explicit etiquette; or they can be illegible and informal, and promulgated by the individual manners of each person in a social scene. Etiquette and manners are different ends of the same spectrum.

Etiquette and manners are both needed in any social scene, and getting the right balance between them is vital to achieving the ends of that scene. —Atlantis on the Hudson, Part 2

We know why etiquette and manners are good and useful in many realms of life. Used properly, they signal that you’re willing to put in effort to demonstrate your good faith, your respect, and your knowledge of other important norms. They are vital social lubricant.

In many ways, they also force you to restrain your initial judgment of people, and require that you get to know them before expressing extreme displeasure.

But many people, with regard to politics, are unmannered barbarians.

They do the equivalent of walking into someone’s house (to which they were warmly invited), looking them up and down, and saying “Your dress is ugly, but at least it distracts me from your face.”

There are many rules of etiquette when it comes to politics, and these change based on context. But, to give you an idea of how I think about this, I’ll tell you the four rules of etiquette in Maximum New York’s code of conduct:

Be as concrete as possible (aka, no bullshitting). Instead of saying “the government should do [x],” strive to say “this specific government agency, operating under this specific law, should do this specific thing in accordance with this law.” Fight the anti-concreteness meme.

Do not use politics as a bad word. One of the most important values of The Foundations of New York City is that government and politics can be forces for good, and that our most virtuous people should go into those fields. Fight the anti-politics meme.

Find the good time. Do not try to have a bad time. Many people in the wider world tacitly or explicitly conflate taking an issue seriously with being mad or miserable about it. I do not, and that general attitude is not acceptable in class (you can get a little mad sometimes, but don’t make it your default). While you’re an MNY student, embrace the pleasant exertion that comes from investigating a new domain with interesting problems.

Extend grace, which here means “giving that which is not earned in the present, in the hope that it will be earned in the future.” Maybe you don’t think someone is worth the benefit of the doubt in the present. Extend it anyway, in the hopes that your positive example will have a transformative effect on others.

Related posts:

You aren’t mentally well

If you’re struggling with depression, isolation, rage, envy, lack of agency, or any number of other potent mental challenges, you will bring those with you into any politics that you do. If someone else is struggling with those things, they will bring them into the politics they try to offer you.

When it comes to politics (social rule-making), apply the oxygen mask rule: secure your own mask first. Before trying to change society, make sure your own house is in order. If you don’t, your politics will likely suffer in quality. You’re also much more likely to be an inadequate advocate, because your own personal issues will not go unnoticed.

This can be challenging, because political movements offer a sense of belonging to many people who desperately want to belong to something.

But meaning is primarily best found in yourself, your friends, your family, and your daily habits, as is mental well-being. Secure them there. Do not anchor them in your politics.

Conclusions and LK-99

Much of my public writing about government and politics isn’t technical analysis. It’s almost like therapy.

Properly engaging with the subject, for most people, isn’t doable. They have too many psychological hangups and bad habits, fundamentally rooted in a lack of knowledge. So, as a civics instructor, I have to put a lot of weight behind remedying those psychological postures. Most civics instructors ignore this part of the job altogether, or reinforce bad habits themselves. It’s a harder endeavor than one might expect.

But I’m working toward a city, state, and country where people are more well-adjusted when it comes to politics. They have good habits, good knowledge proxies, good info diets, and they are well mannered.

This kind of world exists for other domains of knowledge, and I saw it in 2023.

Maybe you were there, maybe you weren’t.

But for a brief second, it seemed like someone had discovered a room-temperature superconductor called LK-99, which would have been a huge breakthrough with dazzling effects for human wealth and prosperity.

For the record, this whole thing was wildly beyond my technical understanding, as it was most people’s. But the common, collective approach many took was: “Wow, I hope the good outcome happens. I don’t really know what’s going on, but I’ll excitedly watch from the sidelines, and see who I can find to be a reliable guide through all this.”

Even though LK-99 didn’t pan out, it was fun, and it was great to see the process of scientific validation happening in real time, especially on Twitter.

Politics is not the same as engineering and physics. But many more politics situations can be like LK-99 than one would expect. Even if you don’t know anything about politics, you can default to the stance of “cheerful spectator,” rather than “It’s definitely all very bad, even though I’m not aware enough to check either way.”

Find the good time. Don’t try to have a bad time.

Excelsior.

Great article. (The two “fight the anti-X meme” links are broken btw)