An Analysis of a Letter from Two NY Congressmen to New York State

It's poor quality, although the ideas it wants to express are good on the merits // You can do better than this letter, and help the system improve // Don't be scared of making mistakes

It’s a drum I beat all the time: almost no one is competent in the broad fundamentals of New York City and State government (take a basic city knowledge test and see for yourself). This is true of the general public, but the point of this essay is to show that it’s true of elected officials and government staffers too. To demonstrate this, I’m going to review a letter sent by two of New York’s federal representatives to the leaders of New York’s state government.

However: I’m not writing this to be discouraging, or to fuel anyone’s impotent anger. Some civil servants know quite a lot, many are happy to learn from others, and the distributed social architecture of government productively aggregates the bits of knowledge contained in everyone’s heads—similar to a private firm. Our system still functions decently, it’s kind of been this way since the beginning, and it’s a result of almost no one addressing the “fundamentals” problem—not malice.

Further: we live in a representative democracy. If you look at the system and you don’t like it, you’re partially angry at your mirror image. Yelling impotently at it without the understanding or capacity to change it only makes you feel bad (which is a large tactical error), and rarely helps anything. If any part of this essay makes you start shaking your fist at the sky, know that it doesn’t make me do that (far from it). We can get coffee to figure out what you can do within your constraints to make things better.

Our system of government could be much better if more people knew more, especially if key elected, appointed, and hired positions understood the robust basics of the city-state (or city-state-federal) system they sit within. This is a massive opportunity for anyone who can figure out how to civically educate New Yorkers at scale, which is what I’m working on.

A letter from two NY congressmen to NYS, regarding state administrative law

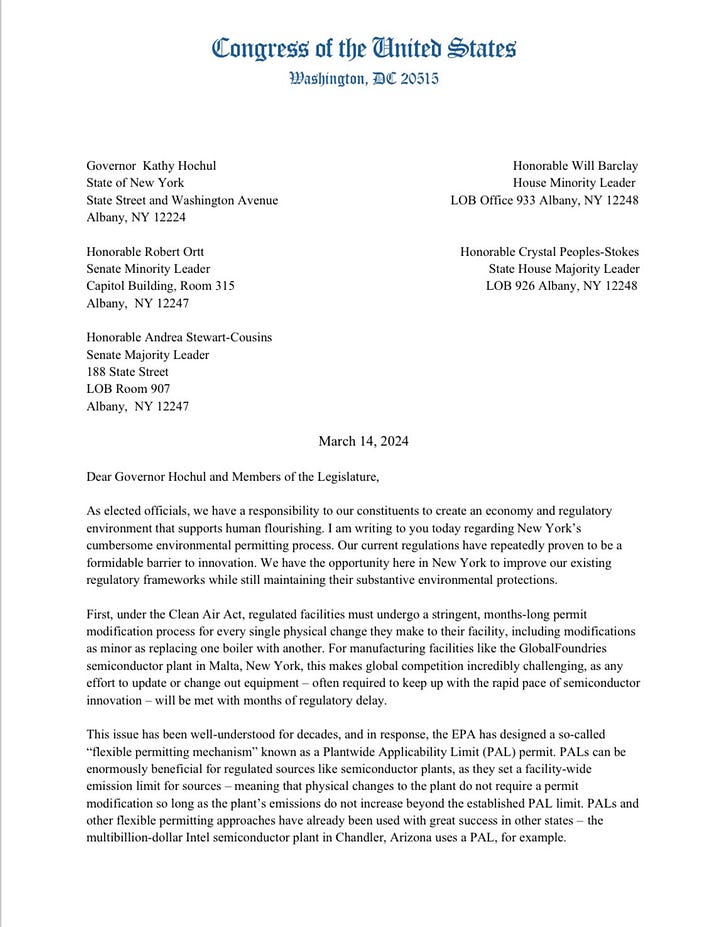

If you spend much time working in the civic sphere, and you understand what you’re looking at, you’ll see “lack of facility with the fundamentals” everywhere. Here’s an example: a letter that two New York members of the U.S. House of Representatives (Brandon Williams and Andrew Garbarino) sent to the governor and state legislative leaders in March of this year. The subject of the letter was overly restrictive (state) administrative law that doesn’t properly balance the state’s need to build and innovate with pollution concerns.

Some errors on page 1, in the order in which they were encountered:

The letter is not addressed to the Speaker of the Assembly! It’s supposed to be to state legislative leaders, but they left out the equivalent of the Speaker of the House at the federal level.

In the letter address blocks, New York State’s lower legislative house is incorrectly referred to as the “House” and “State House.” Not only is the wording inconsistent, it’s incorrect in both cases. NYS calls its lower house the “Assembly.”

The address blocks use an inconsistent amount of spaces between “Albany” and “NY.”

“Chandler, Arizona” in paragraph 3, line 7, should have a comma after “Arizona,” just like “Malta, New York” has in paragraph 2, line 4.

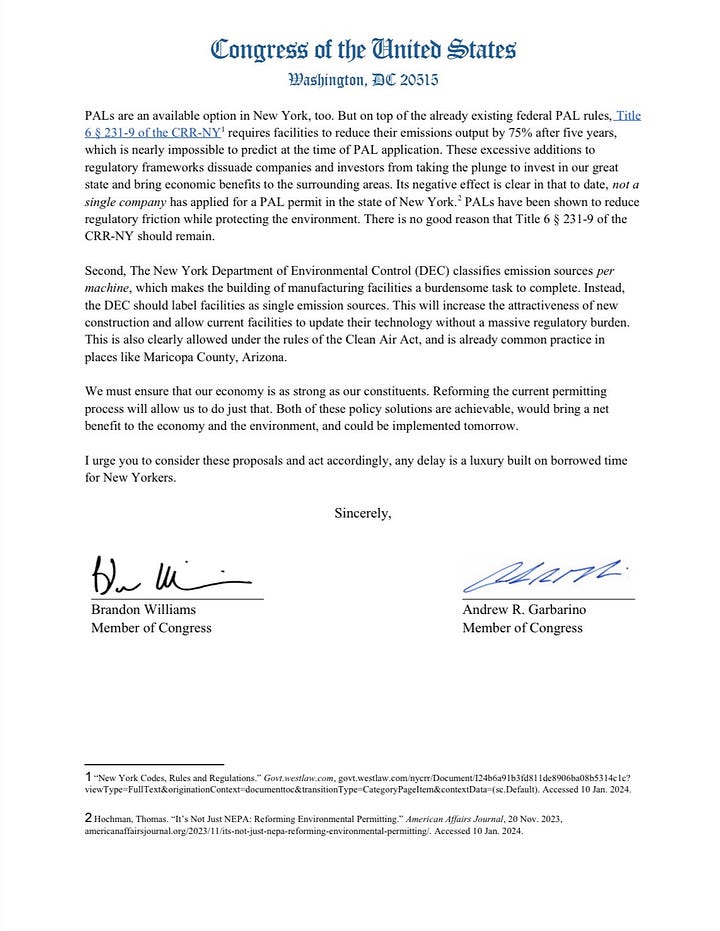

Some errors on page 2, in the order in which they were encountered:

The letter cites state administrative law (“New York Codes, Rules and Regulations”) with “CRR-NY,” which is the atypical way that Westlaw does it, but standard practice is “NYCRR.”1

A huge error: the letter says that relevant administrative law “…requires facilities to reduce their emissions output by 75% after five years…” (paragraph 1, line 2). But the relevant law says (emphasis added): “The PAL level shall be reduced to 75 percent of the initial PAL level…”. So the letter radically misstates the central legal requirement that provoked it—it’s a reduction “to 75%” of previous levels, not a reduction “by 75%.” This is tripping at the starting line.

Another significant error: in paragraph 2, line 1, the letter calls the state regulatory agency of concern the “Department of Environmental Control (DEC).” That agency is, in fact, called the “Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC).”

This letter significantly misstates the central legal claim it purports to concern, and it misnames the agency responsible for promulgating that law. By themselves, these errors would earn an F grade. The widespread nature of the other errors take the grade further into failing territory, and make it an example of inadequate advocacy.

This is unfortunate, because, on the merits, I agree with the two representatives who sent the letter! I agree that the law should be changed as they request, and I am happy to see Thomas Hochman’s good work get cited by federal legislators.

Everyone makes mistakes, and typos come for us all

The point of this post isn’t to pick on the two congressmen (or their staff) who sent the letter discussed above, although I stand by my claims regarding its quality. It’s to reinforce my claim that the bar is low all throughout the government and civil society, and we are dreadfully short of trained talent.

In all likelihood that letter was drafted by staffers who were doing their best, but who had no editor or properly trained senior staff to look it over; that isn’t fully their fault. The representatives themselves trusted their staff to draft something good, and probably don’t have the fluency with New York State law required to immediately catch basic errors in the fundamental claims of the letter (if they reviewed it at all; maybe they didn’t).

This pattern of quality is not confined to any one political party, governmental branch, or level of government. Although I don’t think all the following are equal in magnitude, here are examples of other errors in government publication:

This past week, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) published an internal, draft version of a speech by its chair, Gary Gensler. They quickly pulled it and replaced it with the public version, but the draft is archived. (The SEC’s Twitter account was compromised earlier this year too.)

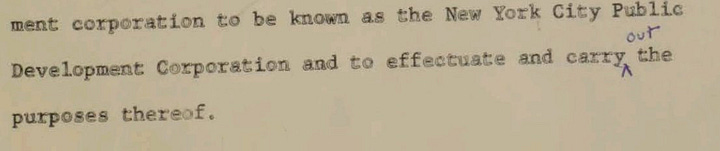

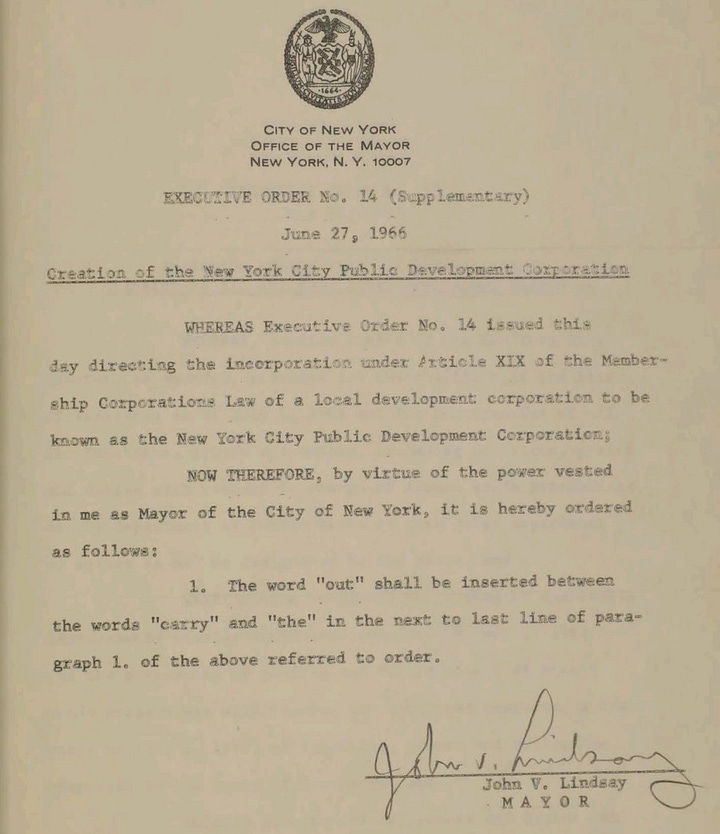

The New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) is an important part of the city’s governing apparatus. One of its precursors was created via mayoral executive order in 1966. This was Mayor Lindsay’s executive order 14—which had to be quickly followed by executive order 14 (supplemental) to correct a typo in the original.2

The New York City Council produces committee research reports to brief members of the council and public about pending legislation. They are frequently scattered with errors. My own personal bugbear is incorrectly cited law (as you might have detected from my NYCRR comments above). Local Law 2 of 2023 (which I reviewed for my “read all the 2023 laws” project) relates to the city civil service, and the October 2022 committee report about it incorrectly cites state civil service law as “CSL,” when it is “CVS.” This might seem small to some people, but it’s an incorrect citation (repeated 16 times) of the report’s core law of concern. This reflects poorly on the report production process in a way that something like a basic misspelling would not.

Footer of page 3 of the October 26, 2022, committee report

I am here to help—focus on fundamentals

There are many things that bring government research and reports to this level of quality. Understaffing is one, salaries are another, but so is the widespread lack of regular training in government and law. Most people are never given a good, foundational understanding of this field, and then they get a job that implicitly requires fluency in it.

As a result, they feel social pressure to “know what’s going on.” They feel reluctant to ask basic questions about government and law for fear of social or professional censure. But I’m here to tell you: everyone should be asking these questions! They should be relentlessly focused on the fundamentals! No matter their level of seniority!3

I called Representative Williams’ office about the letter, since he posted it to Twitter, and told them the legal issues within it. The staffer who answered the phone was kind, cordial, and professional, and he was a credit to the representative’s office. These offices are often filled with hardworking, earnest people. I meant what I said when I said I wasn’t picking on them—you think you’d do any better? They don’t need hectoring, they need help that their congressional offices might not offer!

If you work anywhere in the government on the staff side (or even the elected side), I am on your team. I want you to know how the government and law work. If you ever feel social pressure to not ask questions, and you’re nervous about the correctness of what you’re producing, you can drop me a line (Twitter, LinkedIn, email). I have my own robust calendar of commitments and projects, but I am always happy to do my best to help civil servants.

(Also, can you imagine my own nerves at publishing an essay like this and possibly making a typo?? It’s OK. It happens. I just don’t want to get core things wrong. This is a blog, after all. Let me know if you find one though.)

You can find the executive order in Mayor Lindsay’s collected executive orders here. EO 14 was quickly followed by EO 14 (supplemental) to correct the typo in EO 14.

There are real concerns about status hierarchies though. If you’re in an environment that would ding you for revealing exactly what you know and don’t know, you need to take care to learn more without suffering a grave social wound. Thankfully there are many ways to do this. I’m not blind to the realpolitik of this situation inside agencies, legislatures, and more.

I think this is also a good example of why we should pay congressional/legislative staffers more! Its hard to develop expertise i.e. make a career in this field, when the pay is miserable.