What is a Sanctuary City?

A “sanctuary city” is a city that declines to assist (but legally cannot obstruct) federal enforcement of civil immigration laws.

That definition seems simple enough, until you start tugging on threads. Why can cities decline to assist with the enforcement of enacted federal statute—isn’t federal law supreme? What’s the difference between civil and criminal immigration law? What is the mechanism by which a city “declines”? The list goes on.

“Sanctuary city” is not an easy concept to understand. This is made more difficult by the fact that “sanctuary city” is not a legal designation, and what one city means by it can vary wildly when compared to another. There are also “sanctuary states,” and state law can control the ability of the state’s localities to enact sanctuary policies.

The most confusing thing about the concept out of the gate is that it connotes “immigration law cannot be enforced here, this is a sanctuary from that.” But immigration law can be legally enforced in sanctuary cities.

So what are sanctuary cities really? Let’s take a look.

Table of Contents

Concepts that undergird sanctuary cities

1) Civil Versus Criminal Law

Civil law and criminal law are often mentioned together as two halves of a whole. This can be confusing, because “civil law” actually has several different definitions, and each as a different relationship to criminal law.

Criminal law defines crimes and their punishments. It is accompanied by criminal procedure, which defines the methods that the government and the accused must follow to verify guilt and (if necessary) implement punishment.

Civil law is a broad concept that can refer to: (1) the law that regulates rights and obligations between individuals (contract law, property law, family law, etc); (2) non-criminal law generally; (3) codified law, as opposed to common law (court decisions); (4) administrative law, the laws about, and made by, administrative agencies for regulatory purposes (think DHS, EPA, etc).

For the purposes of this post, I'm focusing on civil law as non-criminal law—particularly the statutory and administrative law that governs immigration enforcement—which uses civil procedure rather than criminal procedure.

Criminal law and civil law vary in key ways. Two examples regarding trials:

Evidence: Criminal law requires the government to meet a higher evidentiary burden when determining guilt than civil law does when finding noncompliance.

Right to a lawyer: There is no right to counsel in civil proceedings like there is in criminal proceedings (no “civil Gideon”).

Why these differences? With regard to evidence: because criminal conviction must determine guilt and punishment, and the accused can have life and liberty directly at stake. People can be locked up or worse based on a criminal conviction (although there is such a thing as “civil detention”)! The stakes of “getting it wrong” are higher than in civil adjudication, which is more about the everyday function of government. With regard to both criminal procedure and the right to counsel: because current jurisprudence interprets the constitution as requiring it.

The takeaway: criminal procedure is often more resource intensive to carry out than civil procedure, and criminal procedure generally has higher hurdles to clear than civil procedure, especially regarding evidence.

2) Dual sovereignty

The United States has a federal system of dual sovereignty; this means both the states and the federal government have separate spheres in which they operate and enforce laws. Some things are only legislated by the states (e.g., most professional licensing), some things are only legislated by the federal government (e.g., coining money), and some things are legislated by both to varying degrees (e.g., criminal law, taxation, marijuana). What determines which sovereign can legislate on something? Fundamentally: the constitution, and those who interpret it, like the Supreme Court.

The line between these sovereignties is constantly shifting. The federal government often wants states to do more on its behalf, and states want to be in charge of their own affairs. The courts largely mediate this tug of war.

If the federal government may plainly not legislate something, but would like the states to do it, they can provide incentives (or threats, depending on where you sit). The most famous modern example is all 50 states converging on the same minimum legal drinking age (MLDA):

Because the 21st amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed States’ rights to regulate alcohol, the Federal Government could not mandate a uniform MLDA of 21. Instead, in 1984 the Federal Government passed the Uniform Drinking Age Act, which provided for a decrease in Federal highway funding to States that did not establish an MLDA of 21 by 1987…Faced with a loss of funding, the remaining States returned their MLDA’s to age 21 by 1988.

But the ability of the federal government to threaten to withhold money is not unlimited. In the 2012 Supreme Court case National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, the federal government heard a challenge against the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). One provision of the ACA expanded Medicaid, and also required states to accept that expansion to keep receiving federal money for Medicaid generally.

The Court held that this threat of funding loss was unconstitutionally coercive (see decision four in the “conclusions” section here):

Chief Justice Roberts, with Justices Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas, Breyer, Alito, and Kagan, concluded that the Medicaid expansion provisions was unconstitutionally coercive as written. Congress does not have authority under the Spending Clause to threaten the states with complete loss of Federal funding of Medicaid, if the states refuse to comply with the expansion.

So you can see that the states and the federal government are constantly renegotiating their authority relative to one another, and that there are various legal doctrines that comprise that negotiation, far more than I’ve mentioned.

Immigration law is squarely within the federal sphere, largely contained in the Immigration and Nationality Act within Title 8 of the U.S. Code (statutory law), Title 8 of the Code of Federal Regulations (administrative law), and court cases that interpret both of these (case law).

Federal law enforcement officers (LEO) can enforce these laws anywhere throughout the nation that they apply. But, although federal LEO can enforce immigration law, they generally cannot compel states (and the localities of states) to assist them. Many states/localities do assist, and they often do so through programs like Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (“ICE”) 287(g) plan. But a growing, significant number do not in varying degrees.

3) The Anti-Commandeering Doctrine

Generally speaking, the anti-commandeering doctrine says that the federal government cannot compel states and their localities to enforce federal regulatory (civil) programs in various circumstances (New York v. United States, 1992). This means DC can’t tell state legislatures to pass certain laws, and it can’t tell the officers of states (governor, sheriff, etc) to carry out federal laws (Printz v. United States, 1997). In other words, it can’t “commandeer” state governments to carry out federal law.1

The anti-commandeering doctrine was established by a series of Supreme Court cases that examined the dual sovereignty inherent in the Tenth Amendment:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

The takeaway: the anti-commandeering doctrine affirms the rights of states to operate as sovereigns independently of the federal government when permitted by the constitution—specifically, they do not have to assist the federal government when it carries out certain federal regulatory/civil law, although they cannot obstruct it. [Note: this is not a blanket permission to get out of federal civil law requirements, and you can find some nuance to the doctrine here.]

So what is a sanctuary city in practice?

1) Defining “sanctuary city”

Now that we’ve outlined the prerequisite concepts of (1) civil v. criminal law, (2) dual sovereignty, and (3) the anti-commandeering doctrine, we can return to the definition of “sanctuary city” that I gave at the top:

A “sanctuary city” is a city that declines to assist (but cannot legally obstruct) federal enforcement of civil immigration laws.

Expanded, this could be explained like this: localities, in compliance with their overarching state law on the subject, may decline to assist the federal government when it seeks to enforce its own civil immigration law in the United States. They may do this because the dual sovereignty of the Tenth Amendment recognizes that states (and their localities) cannot be simply commanded by the federal government in any case. The anti-commandeering doctrine, recognizing dual sovereignty, says that states and their localities may decline to assist in the enforcement of regulatory/civil programs of the federal government, although exactly whether and when they may do this is subject to constitutional interpretation, usually by the Supreme Court.

Since most federal immigration law is civil in nature, and most immigration enforcement is done through administrative law and courts (civil, non-criminal), that means localities are permitted to not assist with most immigration enforcement if they so choose.2

The ways in which they may decline to assist vary. As long as they are otherwise following federal law, they may, for example:

Decline to share information with federal agencies.

Decline to collect immigration status information.

Decline access to city property for the purposes of immigration enforcement.

Decline to notify ICE when they release someone from local or state custody, regardless of whether that person is legally in the United States.

And so on.

2) What are New York City’s “sanctuary laws”?

Although there is no official list, there are about six core pieces of local statute that constitute the heart of NYC’s sanctuary city laws. All of them are aimed at some aspect of “the city shall not assist federal LEO with the enforcement of federal immigration law.”

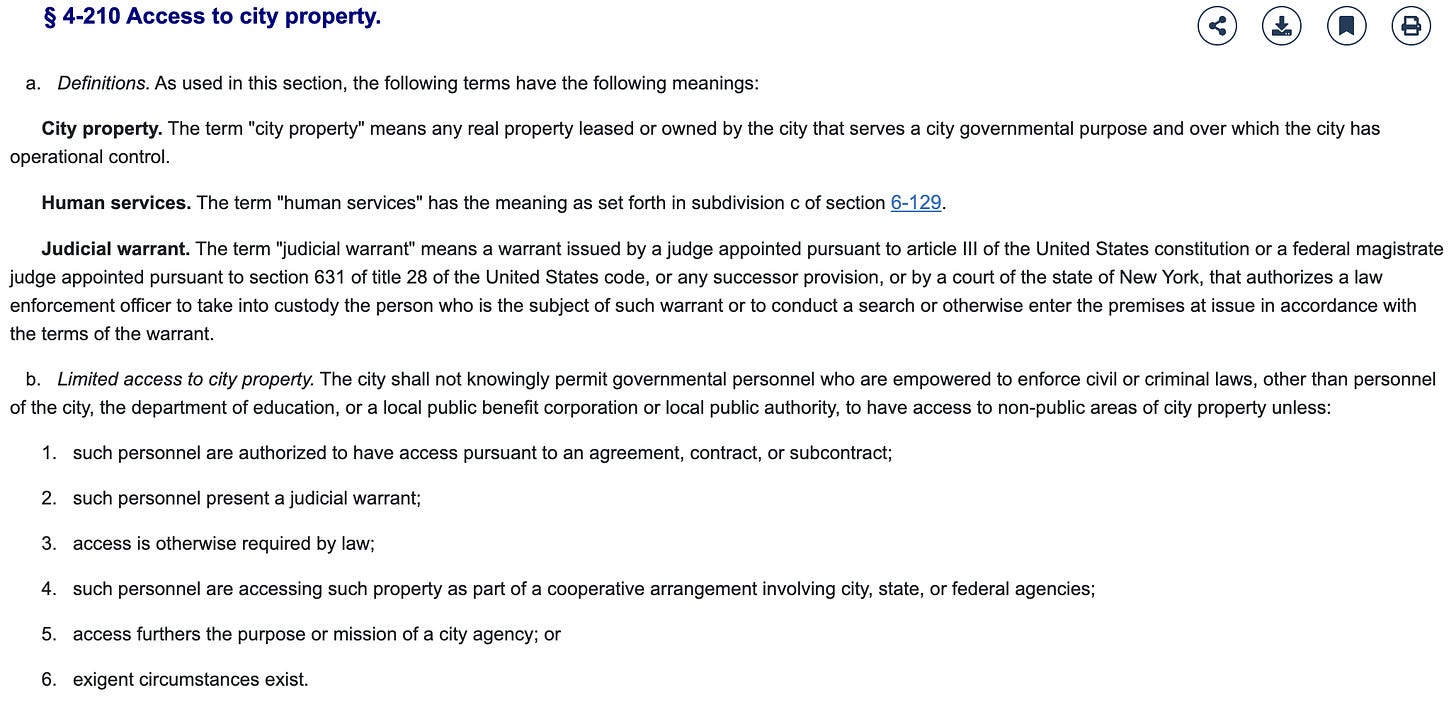

NYC Administrative Code § 4-210: Non-city personnel, including immigration officials, are limited in accessing city-controlled property.

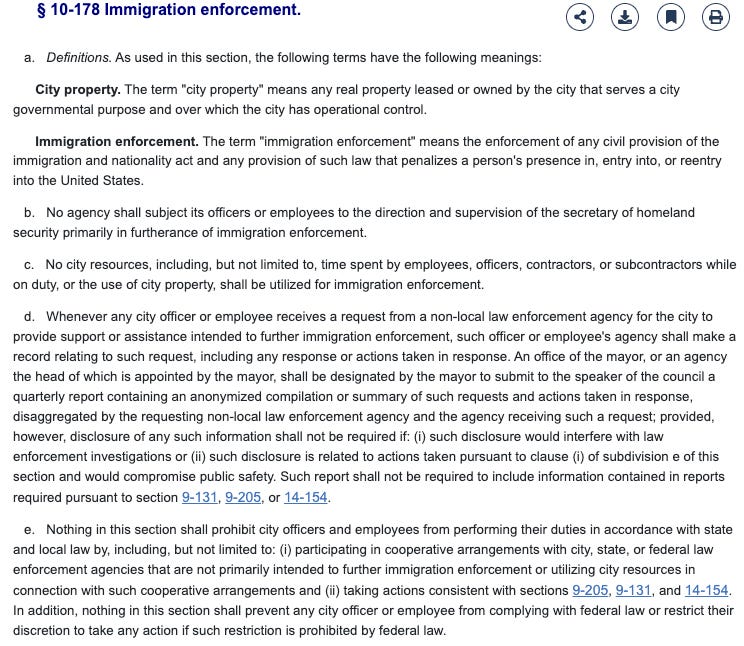

NYC Administrative Code § 10-178: City employee time and resources may not be used for immigration enforcement.

NYC Administrative Code §§ 9-131, 9-205, and 14-154: directions to the Departments of Correction, Probation, and Police to not honor immigration detainer requests from ICE as far as law allows. These sections read very similarly, they’re just directed at different departments.

NYC Administrative Code § 23-1202: The city limits information sharing with immigration officials.

[Note: Int 0945-2024 was a proposal to repeal most of the bulleted laws.]

If you pop open any of the bulleted items above, you’ll see that they’re crafted to operate within the allowable bounds of federal law. § 4-210 broadly limits access to city property, but section (b) lists all the exceptions to those limits, many of them based on federal supremacy or other superseding law. While federal immigration policy and enforcement are not directly mentioned in the law here, you can see that these restrictions are plainly aimed at non-assistance to them specifically by looking at the legislative record. Local Law 246 of 2017 (which created this law) was handled by the Immigration Committee of the City Council, and the committee report summarizes the bill as “…[requiring] that immigration authorities present a judicial warrant to conduct enforcement activities…”3

And take § 10-178 as another, more direct example of non-assistance. Section (a) specifically says “the term ‘immigration enforcement’ means the enforcement of any civil provision of the immigration and nationality act and any provision of such law that penalizes a person’s presence in, entry into, or reentry into the United States.” It then goes on to restrict city assistance with immigration enforcement to such an extent as allowed by law.

And while the laws bulleted above are directly about non-assistance with federal immigration enforcement, there are other laws on the city books that are part of the same sanctuary city mission, like NYC Administrative Code § 21-977, which was added to city law by Local Law 227 of 2017 (“Requiring the DOE to distribute information regarding educational rights and departmental policies related to interactions with non-local law enforcement and federal immigration authorities”).

3) What does “declining to assist with federal immigration enforcement” actually look like?

Example 1: Refusing to honor ICE immigration detainers

While there are several different ways that a locality can decline to assist in the enforcement of federal immigration law, the most salient is refusing to honor civil immigration detainer requests from ICE.

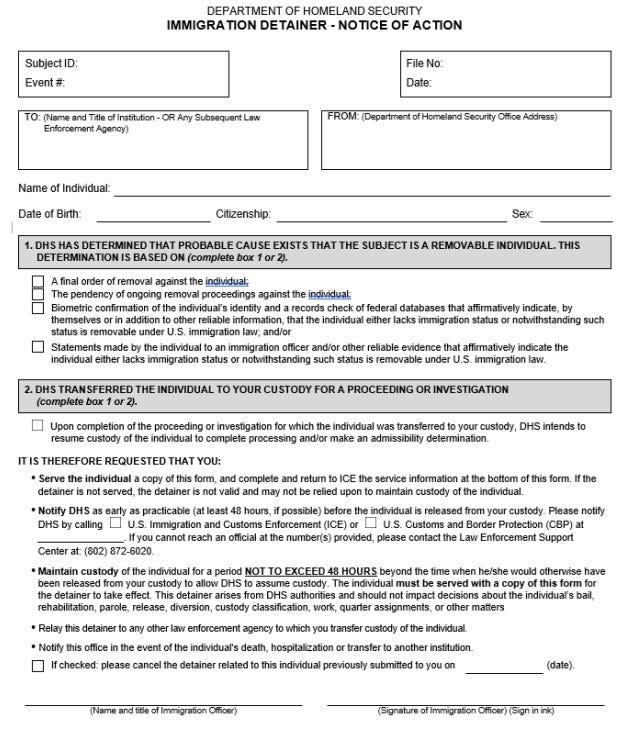

An immigration detainer, in the most literal sense, is DHS Form I-247A, pictured below. It is a civil request that a state or locality hold an individual for up to 48 hours past the time when they would have otherwise been released from state or local custody, so that ICE can take custody of the person. I-247A is a request because it cannot be a command (unlike a judicial warrant from a federal court, which would give ICE or any LEO unilateral authority to execute the warrant).

Per the anti-commandeering doctrine, states and localities may decline to honor these requests. NYC Administrative Code §§ 9-131, 9-205, 14-154 all have a section (b) which flatly states that a detainer request by itself will not be honored. These sections of law refer to the Department of Correction, Department of Probation, and NYPD, respectively.4

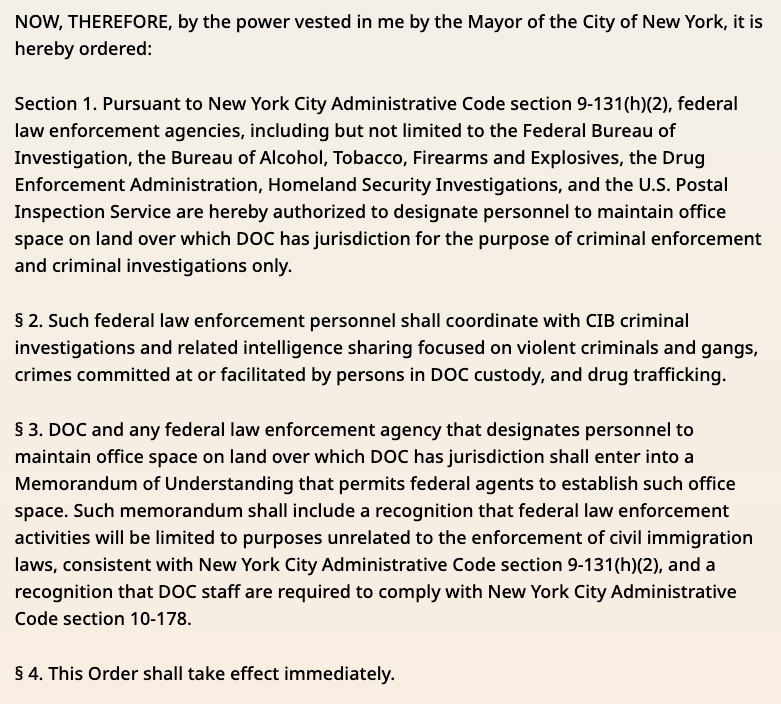

Example 2: Mayor Mamdani’s executive order 01 rescinded Mayor Adams’ executive order 50, which allowed immigration enforcement to maintain an office on property controlled by the Department of Correction

On April 8, 2025, the Adams administration issued Executive Order 50 (“AUTHORIZING FEDERAL IMMIGRATION AUTHORITIES TO

INVESTIGATE CRIMINAL ACTIVITY ON RIKERS ISLAND”), which allowed federal law enforcement to operate out of property controlled by the Department of Correction (which oversees the city jails, among other things). The operational details are pictured below.

This executive order is permitted by one of the “sanctuary” laws mentioned above, NYC Admin Code § 9-131(h)(2), which says (emphasis added): “Federal immigration authorities shall not be permitted to maintain an office or quarters on land over which the department exercises jurisdiction, for the purpose of investigating possible violations of civil immigration law; provided, however, that the mayor may, by executive order, authorize federal immigration authorities to maintain an office or quarters on such land for purposes unrelated to the enforcement of civil immigration laws.”

Mayor Mamdani’s Executive Order 01 repealed Adams’ Executive Order 50: “All Executive Orders issued on or after September 26, 2024, and in effect on December 31, 2025, are hereby revoked.”

This also points to an important idea: “sanctuary city laws” are not in one neat bundle somewhere. They live in statute, are undergirded by case law, and are also implemented via administrative law and…executive orders. NYC’s first such was EO 124 of 1989.

Conclusions

Immigration law is not easy to discuss, and it cuts across surprising lines

Immigration law is thorny, and it’s not an easy thing to wrap your head around. It does not operate intuitively for many people.

Immigration is not a policy focus of this Substack, but I will likely write more in the future. My goal here was to lay down the foundational guideposts for that writing.

I’ll end with some interesting frictions that can arise as you navigate your own opinions in this area.

The civil versus criminal distinction really matters!

There is both civil and criminal immigration law. Civil and criminal law have different procedural requirements, so which side something falls on is consequential.

Entering the United States without due permission is a crime, per 8 U.S. Code § 1325. But you can also face civil penalties for it, per § 1325(b).

Deportation is a civil remedy, not a criminal punishment (not everyone agrees that that should be the case, see here for an example). This means the procedural hurdles tend to be lower—no right to counsel, etc. This is controlled by case law, see INS v. Lopez-Mendoza, 1984 (“Moreover, deportation proceedings are civil actions and the protections afforded defendants in the criminal context do not apply”).

8 U.S. Code § 1227 (“deportable aliens”) lists all of the things that can trigger deportation. They include both civil and criminal actions.

The federal government’s immigration enforcement apparatus is largely civil in nature. This generally allows it to operate faster, but it also means it can be more easily frustrated by states and localities that decline to assist in immigration enforcement.

An exercise for the reader: consider whether and how you would change immigration law. Civil enforcement can be faster, when it’s assisted. Criminal enforcement backed by judicial warrants is more durable, but takes more resources. And so on.

Sanctuary cities exist today because of a conservative Supreme Court affirming states’ rights

Although some “sanctuary action” predates the cases that solidified the modern anti-commandeering doctrine (New York v. United States, 1992, Printz v. United States, 1997), modern sanctuary laws, including New York City’s, rely on the conservative Rehnquist courts of 1992 and 1997 upholding a state’s right to not be commandeered. This was reaffirmed in 2018’s Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association ruling, also from a conservative majority.

[Note: For a further twist, you can read about Arizona v. United States (2012), in which the court limited the ability of a state to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement by means of state statutes that pursue the same ends.]

In each of the four links in this section, you can go see which justices voted which way in each case.

The anti-commandeering doctrine has deep roots going back to the beginning of the United States. I cited two cases that make up part of the “modern” case law for the anti-commandeering doctrine, although you can find others that are older, and even more recent cases that apply the principles of the ones I cite.

Of course there is federal criminal immigration law, and it is enforced through federal prosecutors and federal criminal procedure. But most daily immigration enforcement goes through civil law channels.

You can find the committee report from April 26, 2017, here. See the top of page 4 for the text I quoted.

While there are people who oppose immigration detainers on genuinely ideological grounds (they disagree with the deportation process itself), there are also liability reasons to be careful around them. Some courts have held that the detainers are an unlawful detainment. Here is an articulation of that view.

Thanks! Learning about anti-commandeering doctrine was insightful.

I think one thing that has confused me on civil vs criminal law is my mental model that Civil violations are handled with fines. But deportations / detainment before a deportation go way beyond a fine. I don't know the law around that, but that could be another good "what is" post on this topic.

(To cut to the chase, here's what Gemini said on that question: https://g.co/gemini/share/e46358a12cab)

Very clear explanations, well written!