How to Successfully Reform a Bureaucracy: George Waring & the Department of Street Cleaning

How Commissioner George Waring turned around a department

See this essay’s companion piece: “How Theodore Roosevelt Reformed the NYPD,” which features extensive discussion of Waring.

New York City has many policy problems that are caught in the “triune trap”:

It’s been ongoing for a while,

The city has spent, and continues to spend, increasing amounts of money on it, and

There is no or little discernible improvement, despite all the time and money.

This combination can be infuriating, and the anger can be multiplied by recency bias—the tendency to overweight current events, and discount historical events. People generally do not know, and do not look into, the history of New York City. They are generally unaware of the many times we’ve faced policy problems caught in the triune trap, and how we’ve overcome them. This means they’re overly pessimistic about our ability to escape the trap today, and they automatically assume the past was better at avoiding them. Worse yet: they deprive themselves of past inspiration that could be used to fire their own civic solutions.

This post is a quick sketch of the era when New York City couldn’t solve its trash problem. You might think “don’t we still have a trash problem?”, but I have two things to say to that: (1) we do, but it’s mild by comparison to our first go-around, and (2) our modern trash problem, which is largely confined to bags of trash on the streets, is getting solved.

I will look at two moments in history:

Roughly 1850-1894, when New York City struggled mightily with its trash and sanitation (imagine stepping over piles of horse manure, which dries, flakes, and floats on the wind too).

The election of reformer Mayor Strong in 1894, and his subsequent appointment of George Waring to head the Department of Street Cleaning, the predecessor to the modern Department of Sanitation. Their three years in office, from 1895-1897, transformed the city’s streets for the cleaner.

This post is also partly inspired by Jennifer Pahlka’s book Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better (2023). While Recoding America looks at federal issues in hiring and technology deployment, its lessons are broadly applicable to anyone interested in “making government work.”

So what was New York City’s trash problem like (1850-1894)?

New York City’s population began to explode in the middle of the nineteenth century, and this increase, as well as governmental corruption, broke its ability to deal with trash and sanitation broadly:

A significant portion of the perpetually ballooning budget earmarked for street cleaning found its way into the pockets of local officials…Citizen protests about such shenanigans were met with winks (from insider politicos) or with shrugs (from resigned observers), while the deplorable streets became a national scandal. Public health reformers watched the gains the made in the 1860s disappear while the city stayed squalid and the poor died in droves; infant mortality rates were 65 percent higher in 1870 than they had been in 1810…It seemed that the more funds the Bureau of Street Cleaning received, the less work it did.1

And what, exactly, were New Yorkers dealing with since their streets were not being cleaned?

Created in 1881, [the Department of Street Cleaning] had coped poorly with dirt, ashes, garbage, snow, and the 2.5 million pounds of manure and sixty thousand gallons of urine the city’s horses deposited each and every day along New York’s 250-plus miles of paved streets.2

Before 1895 the streets were almost universally in a filthy state. In wet weather they were covered with slime, and in dry weather the air was filled with dust. Artificial sprinkling in summer converted the dust into mud, and the drying winds changed the mud to powder. Rubbish of all kinds, garbage, and ashes lay neglected in the streets, and in the hot weather the city stank with the emanations of putrefying organic matter. It was not always possible to see the pavement, because of the dirt that covered it…The sewer inlets were clogged with refuse. Dirty paper was prevalent everywhere, and black rottenness was seen and smelled on every hand.3

Imagine wading knee-deep through drifts of rotting organic matter. Imagine the smell. Imagine the flies. Imagine the consequent effects on general health and sanitation! The state of things is simply beyond the scope of modern experience. And yet, despite the pressing nature of the problem, it remained unsolved for decades during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

By 1881, when the Department of Street Cleaning was created (prior to which it was handled by a bureau of the Police Department)4, citizens thought solving the problem of trash essentially impossible. See this excerpt from The New York Times from January 23, 1881. Does the formulation of “We can’t seem to solve it no matter what we do, no matter how much money we spend, even though other cities seem to do it just fine” seem familiar?

It’s a perfect example of the triune trap, and it reflects the resigned depression many New Yorkers had toward their trash problem. So how did New York get out of this situation? What transformed the government such that trash and sanitation were brought under control?

Reformers backed William Lafayette Strong for mayor in 1894, and he brought in George Waring to head Street Cleaning

Mayor Strong was elected by a fusion alliance of Republicans and anti-Tammany Democrats in November 1894. The city was ready to “throw the bums out,” and it did; this was part of a larger wave that saw Republicans take unified control of the state government (governor, legislature, and most statewide offices), and cost Democrats control of both houses of Congress.

One of Mayor Strong’s first acts was appointing George Waring, a Civil War veteran with a long history of public engineering works (including the drainage system of Central Park), to head the Department of Street Cleaning.

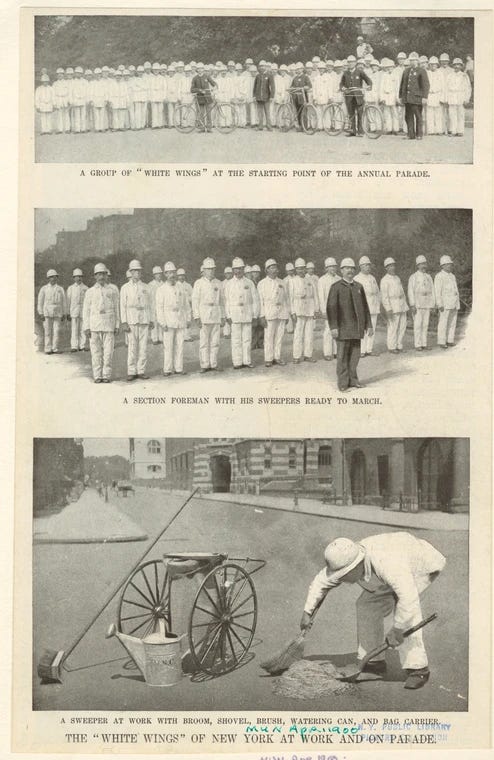

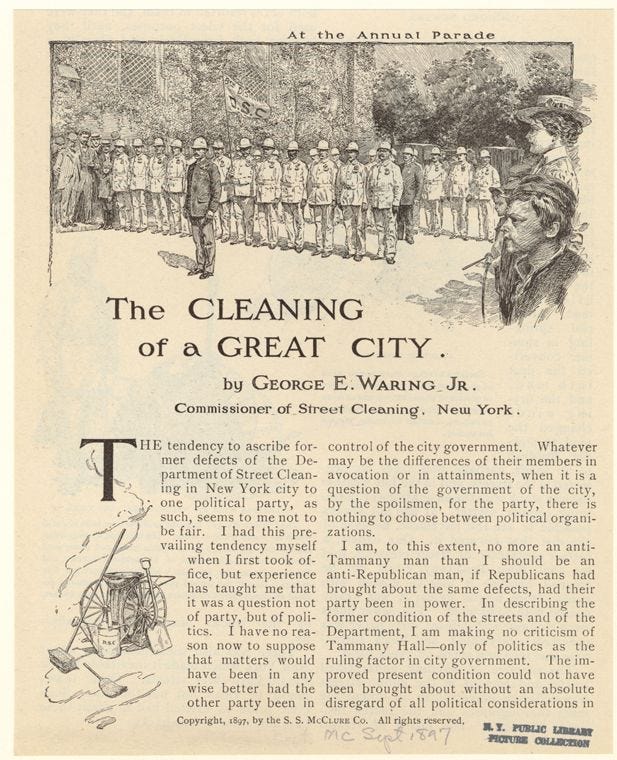

Within months he transformed the department and delivered clean streets to New Yorkers. He delivered ahead of time and on budget. It’s the kind of rapid turn-around reformers dream of. If you want to know how he did it, I recommend starting with his first-hand account—Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes: Methods and Results and the Effect Upon Public Health, Public Morals and Municipal Prosperity, published in 1898. In it, you’ll see pictures like this:

How did Waring do it?

You could write books about this, and others have, but I’ll give you an overview of how Waring achieved so much, so fast. I don’t think it’s anything surprising—Waring focused on improving the quality of his workers, the culture of his department, their methods and techniques, and cross-departmental collaboration:

Quality of workers

The kernel of it all lines in the fact…that men were not employed for work in the Department of Street-Cleaning because they were suitable for the work, but because their appointment was urged by politicians and for political reasons.5

Waring evaluated the efficiency of the staff he inherited, cut the ones who wouldn’t work out, and elevated those with talent—and was allowed a relatively free hand to do this by Mayor Strong and existing civil service law.6 He displayed a practical neutrality in these actions, driven by his need to execute. You can see how “getting the job done” was his primary objective, specifically in an anecdote he tells when evaluating a “Tammany man”:

I found, for example, that the general superintendent had an unusual capacity for handling the roughly organized force employed in the removal of snow. He had been reported to me as a Tammany captain, and as one of the chief agencies through which his political organization had worked the department. He was strongly recommended for dismissal. Remembering the wise injunction “not to swap horses when crossing a stream,” I waited until the snow season had passed. I then sent for him, and told him that he had been represented as a “rank Tammany man,” etc.

He said with mild submission, “Whenever you want my resignation, it is at your service.” I said, “Don’t be quite so fast; let me hear your version of your case.” He said, “Do you know what a Tammany man is? It is a man who votes for his job. I have been a Tammany man, and a faithful one. I have worked for the organization; I have paid regular contributions to it. But I am a Waring man now.” He probably saw an unexplained smile on my face, for he said, “Don’t misunderstand me. If Tammany comes into power again I shall be a Tammany man again.” This frankness met its reward, and I have had the great advantage of Mr. William Robbin’s active and earnest assistance from that day to this, and I trust to have it for many a long day yet.7

Departmental working culture

As Waring got rid of the lower performers, the task of improving departmental morale got much easier. Good work was recognized and rewarded, and Waring also enforced a new uniform policy—street sweepers would wear all white. In 1896, Waring marched these "White Wings" in formation down the streets of Manhattan—the people were thrilled, and this inspired both the citizenry and the street sweepers to keep the city cleaner.

Waring also introduced an arbitration system for labor disputes. Detractors would call it deliberately anti-union, but: (1) it was jointly run by managers and line workers, and (2) it had high satisfaction among the employees themselves. And that latter thing is the real test, anyway.8

Methods and techniques

Although Waring introduced many changes to the Department of Street Cleaning, one stands out: he completely abandoned the use of mechanical street sweepers in favor of manual broom pushers throughout the city.

At first one might be confused—go backwards technologically?? What was Waring thinking? Well, he was thinking clearly, and in a way that responded to the real, on-the-ground context of his time and place. In his own words, here’s why he switched:

Machine-sweeping was formerly almost universal, especially when work was done by contract; and, as a rule, contract street-cleaning throughout the country is executed this way. At the beginning of operations under the present administration there was still a considerable amount of work done by machines, which were employed almost universally at night. The dust raised by them, even with preliminary sprinkling, constituted such a nuisance as to make it improper to sweep by machine during the day. After very careful comparisons of cost and of the character of the work done, it was determined that there was little, if any, economy in using machines if they were made to do the best work of which they are capable, and that it was not possible, under any circumstances, to do such uniformly good work by machinery as by hand. In the summer of 1895 the use of machines was entirely abandoned. Two years’ experience with hand-work has satisfied me that it is incomparably more advantageous than machine-work, and it is not likely that the latter will again be resorted to in this city.9

The mechanical street sweepers just couldn’t deal with the reality New York faced at the end of the nineteenth century, and it would take a clear-eyed reformer to see the solution (although Waring was wrong that street sweepers would “[never] again be resorted to in this city”). As all seasoned civil servants know, just because you can do something with technology, doesn’t mean you should. The end result is always the measure of performance.

Civic collaboration

Waring and his team enlisted the city’s children to help them—not only were the children happy, willing participants, but they were especially helpful in communicating with the large amount of recent immigrants to New York. Then, as now, the children of immigrants served as their parents’ translators and portal into wider American life.

Waring accomplished this with “Juvenile Street-Cleaning Leagues,” which came with classroom presentations in schools, songs, membership cards, civic pledges, and more:

Every child is given a paper on which to record at the end of a week the number of persons or other children to whom he may have spoken about the matter of keeping the city tidy and neat; the number of bonfires which he has succeeded in stopping; the number of skins which he has kicked into the gutter from the sidewalk; the number of papers he has induced others to put in the barrel instead of on the pavement; and various things of a similar nature. On the basis of such reports, badges are given out, ranking the children as “Helpers,” “Foremen,” or “Superintendents.” Special work and interest is rewarded by advancement and the assignment of some particular department title, together with a certificate of authorization from the commissioner.10

This way of engaging with children, and through them the broader city, fed into the virtuous cycle of mutual respect that joined street sweepers themselves to the populace.

Cross-departmental collaboration

Of course, when Waring took office, the people of New York had terrible trash habits. They dumped everything out onto the street, no matter how putrid or horrifying, and the laws against such behavior hadn’t been enforced in a long time. You can get a long way by simply cleaning the streets—people see that there’s a point to not littering, since the street is being cleaned. But you can’t get everywhere with merely cultural change:

A good deal of time might be employed in the enumeration of culpable acts and shameful delinquencies on the part of the merchants and householders…Such things were not done, perhaps, because the offenders had resolved to be blameworthy and contemptuous, but because they were imbued with the spirit of indifference to the public welfare and had long been accustomed to do such things without fear of the law.11

That meant collaborating with the police department. Prior to Mayor Strong, the police department had been devastated by scandal; the state Lexlow report, at over 10,000 pages long, cataloged vast corruption and graft.

Thankfully the police department was headed by another reform-minded appointee from Mayor Strong: Theodore Roosevelt.

Waring especially needed help to ensure compliance with his new recycling program (one of his many other innovations):

To solve all these problems at once, Waring in 1896 required that householders put out their ashes, their garbage (organic animal and vegetable wastes), and their rubbish (drystuffs such as paper, cardboard, tin cans, bottles, shoes, carpets) in separate containers. Mayor Strong assigned him forty policemen to ensure compliance. Department employees then then sent ashes—along with street sweepings (mainly dirt)—to be dumped at Riker’s Island rather than at sea, along with rubbish, once it had been scavenged by scow trimmers for salable items. Finally, Waring contracted with the New York Sanitary Utilization Company to pick up garbage and take it to a plant on Barren Island in Jamaica Bay. There “digestors” cooked and stewed it until oil and grease were separated out for sale to manufacturers, and the residue was dried and ground into fertilizer.12

Lessons for politicians and appointed officials from Waring’s story

The divide between a well-run city and badly run city is not inherently “Republican versus Democrat.” It is “those who execute, and those who don’t.”

Per Waring, in chapter three of his book, entitled, “The effect of political control as shown by the condition of the department at the beginning of the present administration”:

I have no reason now to suppose that matters would have been in any wise better had the other party been in control of the city government. Whatever may be the differences of their members in avocation or in attainments, when it is a question of the government of the city by the spoilsmen for the party, there is nothing to choose between political organizations.13

Give your people freedom to execute

One of the best things a New York City mayor (or any governmental executive) can do is appoint competent people to head the governmental departments, and let them execute. They should not be micromanaged, and they should be given political air cover to do their jobs. Mayor Strong did this for Commissioner Waring, so much so that, among other things, Waring dedicated his book to the mayor who let him operate.

Waring showed his understanding of this dynamic with a graceful appraisal of his predecessor, who did not have a reform mayor watching out for him like Waring did, and who otherwise handed Waring a mess of a department:

I have no knowledge of the methods prevailing under the predecessors of Commissioner Andrews; but I do know that he had done the best that he could, under his limitations, to improve the situation. The department still feels, and always will feel, the influence of his intelligence and zeal in the theoretical part of his work. He secured the passage of several amendments to the law organizing the department which are of the greatest value—amendments which could be obtained now only by an influential Republican politician, and without which good work would be almost impossible.14

Spending more money does not equate to better outcomes, and is not an inherent measure of improving a policy area

As mentioned above, the street cleaning budget continued to rise prior to Waring, but the results weren’t better. Per Waring:

[The terrible conditions of the department’s equipment] is a severe condemnation of a department that spent $2,366,419.49 in a year (in 1894), as against $2,776,479.31 in 1896, and did ineffective work with it…15

You can see that Waring barely increased the overall expenditure of his department when compared to his predecessor (an impressive feat given all the catch-up capital investment he had to do)—but got far better results and a functioning department. I noted a modern day example of “money doesn’t equal results” in my overview of the New York City Department of Education budget.

Waring’s legacy

Mayor Strong, and Waring as a result, were swept from office in the 1897 elections. They were replaced by Mayor Van Wyck, who was a Democrat and “Tammany man.”

Their tenure was only three years long, and the Van Wyck administration did begin to roll back the efficiencies of Waring, but the public had seen what was possible. They would no longer accept “more money, but no results” for street cleaning.

So not only did Waring’s legacy live on in raised civic standards, he would be an inspiration for other reformers (myself included!) about what was possible in city government. Just because something hasn’t been solved by others, even if they had more time and money than you, doesn’t mean you can’t fix it with the right team and approach. You just have to work the problem.

…reformers adored Waring: he was their first star. He demonstrated that despite Tammany taunts about goo-goo ineffectiveness, reformers could deliver. The man provided businesslike nonpolitical efficiency, fostered civic pride, advanced a godly cleanliness, and, via a ruthless paternalism, kept labor in line and productive. For having so thoroughly proved there were viable alternatives to machine rule, they would in 1898 elect him president of the City Club.16

Supplemental bibliography for further reading:

Waring, George, Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes: Methods and Results and the Effect Upon Public Health, Public Morals and Municipal Prosperity (1898).

Nagle, Robin, Picking Up: On the Streets and Behind the Trucks with the Sanitation Workers of New York City (2014).

Nagle, Robin, Chapter 8 “A Matter of Spoils,” Picking Up (2014), p.101.

Wallace, Mike, Burrows, Edwin. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press, 1999, p.1194.

Waring, George, Chapter 3 “Political Control,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes (1898), p.13

Chapter 1, “History,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.1

Chapter 2, “Conditions Under Recent Administrations,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.6

Street cleaners were still “permanent employees” who could only be dismissed “for cause,” but “for cause” was weaker then than it is now.

Chapter 3, “Political Control,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.18

This body was called “The Board of Conference,” and is detailed beginning on page 26 of Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes.

Chapter 5, “Street Sweeping,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.38

Chapter 14, “The Juvenile Street-Cleaning Leagues,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.180

Chapter 1, “History,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.2

Gotham, p.1196

Chapter 3, “Political Control,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.12

Chapter 2, “Conditions Under Recent Administrations,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.10

Chapter 3, “Political Control,” Street-Cleaning and the Disposal of a City’s Wastes, p.16

Gotham, p.1196

Great post. Interesting question of how to apply these methods and principles to contemporary problems.

Great post! I especially like the point about mechanized street sweepers. Here in the US we often think we can use technology to solve all our problems, when really it is usually personnel or procedure that need improvement.