SpaceX, Starship, and NY's Erie Canal

What is New York's place in the space economy? // Lessons from the Erie Canal for the Space Age

Yesterday, SpaceX pushed the frontier of rocketry forward, and pulled humanity’s future as a spacefaring economy and people closer. It caught Starship’s booster stage as it flew back to Earth, and Starship had a successful splashdown on the other side of the world. You can watch the whole thing here.

But: most people do not realize the broader significance of what SpaceX is bringing into reality. Among other things, it is lowering the freight cost of sending things into low earth orbit (LEO) and deeper space by orders of magnitude. Once Starship is flying regularly, which seems inevitable at this point, the world will be transformed by the sheer force of suddenly affordable space freight rates.

You might wonder why I’m writing about this on a blog called Maximum New York, where I usually focus on the politics, history, and other goings on of our great city and state. Well, it’s because we’ve seen the story of SpaceX before (or at least a version of it), so we can predict some of what’s to come—and take full advantage of it.

It’s the story of the Erie Canal.

The Erie Canal and the Dawn of New York

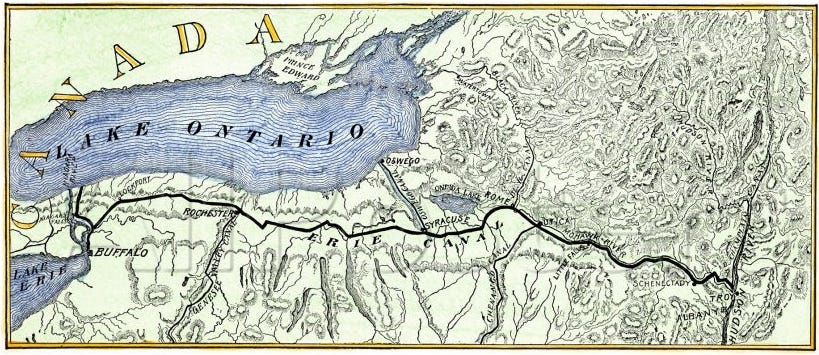

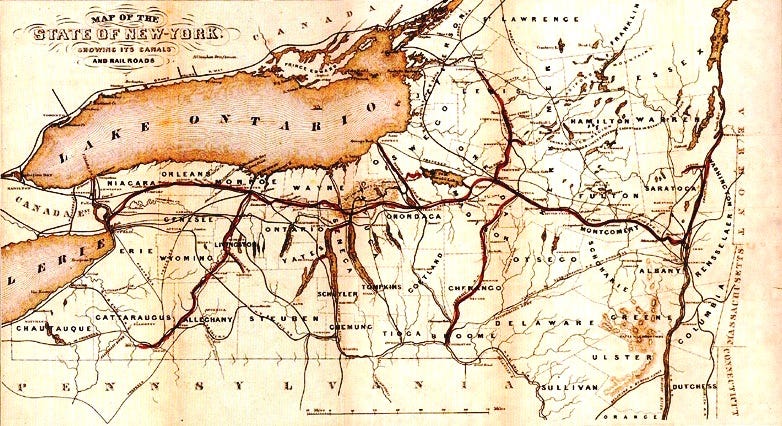

The Erie Canal was constructed between 1817 and 1825, and upon its completion it radically transformed the fortunes of New York City, New York State, and the whole of the United States by connecting the Great Lakes region to the coast:

By cutting freight charges between Buffalo and New York City from $100 to $10 per ton and by reducing hauling time from twenty-six to six days, the waterway made the city a transfer point for grain, lumber, meat, and other products from the Great Lakes region to the upper Mississippi Valley. Indeed, the Erie Canal carried so much traffic that in only seven years the State of New York recovered the $8 million cost of construction.1

Not only did the canal reduce overland freight costs by an order of magnitude, it enabled branch canals and other infrastructural improvements that compounded its initial effects even further.

It’s hard to overstate the scale of achievement that the canal represented at the time. It was constructed with manual labor, manual siting equipment, and far more precarious finances than many infrastructure projects today.

There were detractors

The difficulties in construction and finance were the reason why many contemporary people thought it was an impossible undertaking, and why it was widely derided as “Clinton’s ditch,” after Governor DeWitt Clinton who championed it.2 Of course, the governor was correct, and the naysayers were wrong—a common pattern throughout New York and America’s history. That same impulse has come after almost everything modern New Yorkers love, and in the modern day it comes after everything we need for a brighter future. It has ever been thus.

The Power of Bringing Freight Rates Down By >An Order of Magnitude

The Erie Canal’s immediate effect was forcing shipping rates down by at least an order of magnitude, and increasing the rate of that shipping. This meant that more goods were shipped, a larger variety of goods were shipped, and human activity across many domains—commercial and otherwise—were greatly stimulated all around the country. More people had access to more, for less. The energy of the whole system rocketed upward, and New York City’s place as the center of commerce for the nation and continent was cemented, even as the canal was also a boon for places like Chicago.

Forever onward, the Erie Canal would be a symbol of a particular kind of Great Public Improvement.

SpaceX is the Space Canal

SpaceX has been bringing down the cost of shipping things to space, and increasing the rate of launches, with its Falcon 9 rockets (and their Merlin engines); but its upcoming implementation of Starship represents a huge leap even beyond Falcon.

I’ll quote from Casey Handmer’s blog to give you an idea of the scale. From his 2021 piece, Starship is Still Not Understood (emphasis added):

Enter Starship. Annual capacity to LEO climbs from its current average of 500 T for the whole of our civilization to perhaps 500 T per week. Eventually, it could exceed 1,000,000 T/year. At the same time, launch costs drop as low as $50/kg, roughly 100x lower than the present. For the same budget in launch, supply will have increased by roughly 100x.

The effects of this price decline will ripple across America and the world. Entire industries will be reshaped. Wealth will flow further and faster, and broad-based opportunity will increase. In addition to a totally new space economy, LEO projects like Starlink, which are a direct benefit to Earth right now, will expand.

Handmer paints a picture of the industrial transformation we can expect:

Historically, mission/system design has been grievously afflicted by absurdly harsh mass constraints, since launch costs to LEO are as high as $10,000/kg and single launches cost hundreds of millions. This in turn affects schedule, cost structure, volume, material choices, labor, power, thermal, guidance/navigation/control, and every other aspect of the mission. Entire design languages and heuristics are reinforced, at the generational level, in service of avoiding negative consequences of excess mass. As a result, spacecraft built before Starship are a bit like steel weapons made before the industrial revolution. Enormously expensive as a result of embodying a lot of meticulous labor, but ultimately severely limited compared to post-industrial possibilities.

Starship obliterates the mass constraint and every last vestige of cultural baggage that constraint has gouged into the minds of spacecraft designers. There are still constraints, as always, but their design consequences are, at present, completely unexplored. We need a team of economists to rederive the relative elasticities of various design choices and boil them down to a new set of design heuristics for space system production oriented towards maximizing volume of production. Or, more generally, maximizing some robust utility function assuming saturation of Starship launch capacity. A dollar spent on mass optimization no longer buys a dollar saved on launch cost. It buys nothing. It is time to raise the scope of our ambition and think much bigger.

New York’s Place in a Space Economy

The power of geography

SpaceX is based in Texas, and favorable and legacy launch sites are in the southern United States—think of Cape Canaveral in Florida or Vandenberg in California. This is an advantage of geography: launching closer to the equator takes better advantage of Earth’s rotational speed.

New York once took advantage of its geography by building the Erie Canal: it lay between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes, and its pre-eminent city sat on a deep, protected harbor that just happened to link to its capital city (and the canal) via the Hudson river. The ambition of the canal was rewarded greatly.

But New York does not have the advantage of geography that the space economy prizes for launches, latitude.3 (And, honestly, its regulatory apparatus is probably prohibitive at the moment, even if it were latitudinally appropriate.)

How will New York integrate into a space economy?

So I wonder: while Texas will (probably) primarily benefit from the launch operations of SpaceX, including the massive amounts of wealth that will accompany it, how will New York? It cannot afford to stand to the side, nor should it. It is a capital of finance, culture, tech, and almost any field you can imagine. It is well positioned to build on these strengths to take advantage of what’s coming.

New York has ridden the freight-reduction moments of canals, railroads, container ships, and more. We will ride to space as well.

A word of warning: New York won with its canal, and other cities lost as they struggled to catch up:

The canal was the right improvement at the right time. It enabled New York to exploit the water-level route through the Hudson and Mohawk valleys at a time when its rivals remained trapped behind higher mountains. Although the success of the Erie Canal prompted Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., to try building their own waterways in a desperate bit to keep pace with New York, none of these cities could match the pioneer. Baltimore eventually abandoned its project as a total failure, while massive investments were required to finish Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Portage and Canal system…and Washington’s Chesapeake and Ohio Canal…Moreover, both waterways immediately faced strong competition from a new source of transportation, the railroads, which made them obsolete.4

Of course, other cities won, like Chicago, which would come to threaten New York’s position toward the end of the nineteenth century because of both the canal and, later, the railroads:

European banking and export firms might shift their American branches to the heartland; corporate headquarters would soon follow, taking professional firms along; the market prices of stocks and commodities would get set in the interior; manufacturing would steal away; New York’s property values would scud downward. Doomsayers recalled how the power and prestige of Philadelphia, once America’s chief city, had slowly bled away once it was surpassed numerically by its Hudson River rival.5

Which way, Metro Man?

How will the capital of the Earth embrace space, when humanity is no longer confined to one planet? That moment is a single-digit amount of years away, if we are already not in its initial moments.

Our economy and wealth are already moving off planet in a way that’s mutually beneficial to surface and sky, and that will only accelerate.

I’d love to hear from those in the city and state government, as well as private industry, who are planning for the coming boom in reduced space freight prices and increased launch cadence.

Let’s make sure New York grows from a metropol to an astropol.

Hood, Clifton, “The Great City,” 722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York; 2004 (Centennial Edition), p. 34.

The Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, Rapid Transit in New York City and in Other Great Cities; 1905, p. 3.

You can launch from higher altitudes, and the U.S. does, but the price and ease of higher latitude launches make it more challenging.

722 Miles, p. 34.

Wallace, Mike, Burrows, Edwin. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 1223.

Further, from Andrew Haswell Green’s New York of the Future: Writings and Addresses by Andrew Haswell Green (1893), p. 29:

It is not impossible that some competing intelligences demonstrating upon other lines, and some co-operative ignorance demonstrating upon our own, may in time bring about the result that New York shall be operated in the chief relation as a seaport and serve to some interior position the secondary use that Hamburg renders to Berlin, that Havre rends to Paris, Southampton to London…”

New Yorkers’ fear of an ascendant Chicago wasn’t helped when it won the 1893 World’s Fair:

“This fear took tangible form in 1890, when Congress gave the midwesterners the go-ahead…The idea of a World’s Fair had been broached back in 1882, and ever since the two colossi had been competing for it furiously. Defeat seemed another doleful indicator of metropolitan decline” (Gotham, 1223).