NYC Debt, Part 1: Bond Basics

General Obligation // Future Tax Secured // Revenue

Understanding how the city takes out debt is vital to understanding how it works. And while there are many forms of debt instrument that the city uses, you can get most of the picture by understanding two things:

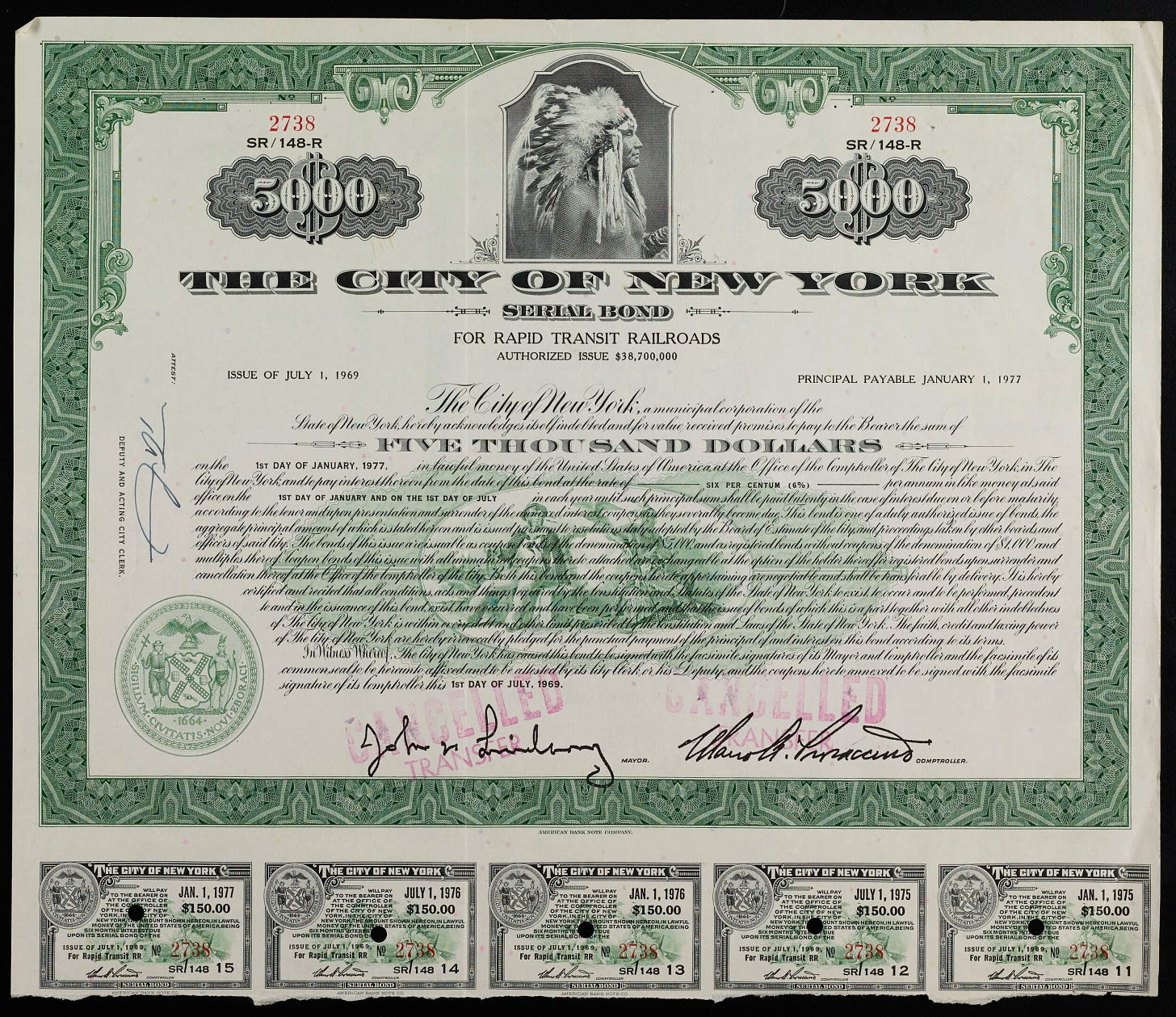

Debt usually takes the form of bonds.1

New York City makes use of three core kinds of bonds: general obligation, future tax secured, and revenue.2

What is a bond?

A bond is “an obligation to pay a specified amount of money.” It is the usual way that the city “takes out debt.”

It has four basic components:

Principal: the face value of the bond. Let’s say $100.

Interest: the money on top of the principal that is paid to the bond holder during the life of the bond. If it’s 1%, then that would be $1 on a $100 bond (paid out at set intervals, like a year).

Maturity: the life of the bond. Interest is paid during the life of the bond, after which the principal is returned. Bonds can have a maturity of decades, and can also be retired early.

Collateral/backing: what is the bond backed by? What makes bondholders trust that the bond, and its interest, will be paid?

What is the purpose of city bonds?

From the city comptroller’s website:

New York City sells bonds to finance the construction and repair of infrastructure projects such as roads, bridges, schools, water supply, and wastewater treatment systems. The City determines projects through the capital budgeting process. Projects must have useful lives of five years or longer to be funded by debt (three years or longer for information technology projects).

New York City also issues bonds to refinance outstanding bonds for interest savings, which saves money for taxpayers and ratepayers. Refinancing bond sales are strictly economic and do not extend the final maturity of the debt or cause increases in debt expense.

What kinds of bonds are in “New York City debt”?

While there are more specialized forms, almost all of NYC’s bonds fit into three categories:

General Obligation (GO) bonds, issued directly by NYC and backed by its general taxing authority.

Future Tax Secured (FTS) bonds, issued by entities like the Transitional Finance Authority (TFA), and backed by directly intercepted personal income tax (city can’t touch it). This specific pledge of a dedicated tax revenue that the city can’t otherwise use is distinct from a general obligation.

Revenue bonds, issued by authorities like the Municipal Water Finance Authority, and backed by specific, non-tax revenue streams like water charges.

GO bonds are paid through NYC’s regular annual budget process; FTS and revenue bonds are paid from their pledged revenues.

⭐️ Important to note: NYC has a debt limit set in the New York State Constitution; it’s a function of the full value of property within the city (article 8, section 4(c)). In order to get around this debt limit, both the city and state have created separate entities that can issue debt (bonds) in their own name. Even though these bonds might pay for city infrastructure, they do not count toward the city’s debt limit unless specified in state statute. The Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) mentioned above is one such “financing authority.”

1) General Obligation (GO) bonds

GO bonds are sometimes also called “full faith and credit” bonds, because they are backed by the general taxing authority of the city, and are repaid by appropriations in the city’s annual budgeting process.

As a recent GO bond offering says (page 2):

The Bonds are general obligations of the City for the payment of which the City has pledged its faith and credit. All real property subject to taxation by the City is subject to the levy of ad valorem taxes, without limitation as to rate or amount, to pay the principal of, applicable redemption premium, if any, and interest on the Bonds.

2) Future Tax Secured (FTS) bonds

FTS bonds are backed by a specific stream of tax revenue that the city cannot touch. The state collects the money and sends it to the bond issuer to service their bonds.

The Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) issues a lot of these bonds to help finance New York City’s capital program. TFA FTS bonds are backed/serviced by city personal income taxes; the state collects these taxes and transfers them directly to the TFA. In the event that the city does not yield sufficient income taxes, the state (comptroller) can transfer city sales tax revenues to the TFA to cover the difference; this hasn’t yet happened.3

If you want to know more about this, I can recommend no better source than an Offering Circular of TFA FTS bonds itself. Take a look at the “Summary of Terms” section on page 1 (you have to scroll a bit before hitting numbered pages).

3) Revenue bonds

Revenue bonds are backed by a specific, non-tax revenue stream that will be used to service the bonds, like tolls. You often see these issued by the public authorities or development corporations that operate alongside/within New York City. For example:

The Tobacco Settlement Asset Securitization Corporation (TSASC) issues bonds backed by payouts from tobacco companies resulting from a 1998, nationwide settlement:

TSASC, Inc. (“TSASC”) is a local development corporation created pursuant to the Not-For-Profit Corporation Law of the State of New York. TSASC was created as a financing entity whose purpose is to issue and sell bonds and notes to fund a portion of the capital program of the City of New York (the “City”). TSASC issued debt secured by tobacco settlement revenues (“TSRs”), which are paid by cigarette companies as part of their settlement with 46 states, including the State of New York, and other U.S. Territories. The City sold its right to receive TSRs to TSASC. TSASC’s stakeholders are its bondholders, who have purchased TSASC bonds and the City, which benefits from the contribution of TSASC to its capital program.

See this old Independent Budget Office page when the TSASC was first created for cool detail.4

Separately, other authorities that serve the city, but wouldn’t contribute toward “city debt,” also issue revenue bonds. The best example is the MTA.

The MTA (Metropolitan Transportation Authority), which is a creation of the state, issues revenue bonds that are backed by multiple revenue streams, including fares from its subways and buses. In S&P’s recent overview of the MTA’s revenue bonds, they note that the MTA’s creditworthiness is impacted by how well it can secure the revenue that backs their bonds:

We base the upgrade on several factors we view as providing additional stability and predictability to MTA’s credit profile, including New York State’s decision to increase the payroll mobility tax for MTA’s capital programs, the initial financial success of MTA’s Manhattan congestion pricing program, ongoing recovery in ridership levels, maintenance of healthy liquidity levels, clarity regarding funding sources of the recently approved 2025-2029 capital program, and manageable projected out-year deficits.

Here the report highlights downside credit risk specifically (emphasis added):

We could lower the [Standard & Poor’s Underlying Rating] over the two-year outlook period if weaker fare and toll revenue performance causes persistently weaker all-in net debt service coverage (S&P Global Ratings-calculated) or if we believe the funding of the authority’s capital needs materially weakens MTA’s debt-to-net revenues and liquidity metrics.

This is directly relevant to public discourse. For example: free subways or buses would cause problems with MTA bonds backed by that revenue. As Nicole Gelinas notes in City Journal, navigating that issue successfully will be a key thing to watch in New York City’s near-term future.5

Learn more about city bonds and debt

I’m going to write more posts about bonds and city debt in the future, but you can explore on your own by visiting the city comptroller’s website.

You can also sign up for bond sale email alerts. It’s one of my favorite emails to read.

A lot of what you read will make sense if you’ve mastered the concepts of general obligation, future tax secured, and revenue bonds.

Both New York City and the various entities serving it, like the MTA, use non-bond debt instruments, like lines of credit, although bonds remain the primary form of taking on debt.

In a future post I will discuss other forms of bond like moral obligation, social, etc.

Per page 4 of the TFA FTS 2025 bond offering circular: “A transfer of Sales Tax Revenues to the Authority has never been required.”

If you read any of the bond offering documents (see the third page) from TSASC, you’ll see the separation between it as a corporation and the city of New York: “TSASC, Inc. (“TSASC”) is a local development corporation organized under the Not-For-Profit Corporation Law of the State of New York (the “State”). TSASC is an instrumentality of, but separate and apart from, The City of New York (the “City”).”

Many localities in New York have a “securitization corporation” that uses tobacco settlement money to back bond issues (see this example). There are 37 by the count of this 2015 state comptroller report (per page 4).

Page 8 of S&P’s review of MTA bonds highlights the direct relationship between cutting fares and taxes; if one goes down, the other must go up: “We believe it is possible that the proportion of tax-supported subsidies could grow, particularly if the state and city provide MTA with additional tax-supported subsidies to fund its significant capital needs and neutralize revenue loss from lower paid ridership.” However, as Nicole Gelinas notes in City Journal, one cannot effortlessly substitute appropriated state money for a fare in a bond covenant.

Great breakdown Daniel, excited for more of this series. I also wanted to add that in my own research on NYC's budget and debt, I've discovered great resources from the IBO: https://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/understandingthebudget.pdf.

Some very fascinating insights in these reports, such as how, in 2020, NYC's outstanding debt came out to $11,390 per NYC resident. In that year, the City also had more outstanding TFA debt than GO debt!